Key Findings

State regulators and potential project investors need to scrutinize assertions that hydrogen gas will be widely used in methane-fired turbines.

Lack of supply, lack of pipeline infrastructure, and lack of storage capacity will slow and perhaps entirely halt the widespread use of hydrogen as a replacement for methane in turbine generators.

The costs of wind, solar and storage are known today, while the ultimate cost of any “hydrogen-capable” turbine will not be known for years.

Hydrogen-related power projects require significant additional investments that will be extremely costly for ratepayers, may not actually work and will conflict with readily available and cheaper renewable options.

Executive Summary

Electric utilities and project developers have latched on to the “hydrogen-ready” and “hydrogen- capable” tags in describing their plans to build new methane gas-fired (popularly called natural gas-fired) power plants. State regulators and potential project investors need to scrutinize assertions that hydrogen gas will be widely used in methane-fired turbines. IEEFA concludes that these assertions amount to little more than marketing designed to obscure the myriad shortcomings and unanswered questions associated with using hydrogen in methane-fired turbines, particularly regarding the enormous cost and lengthy time that would be required to build out the infrastructure needed for such a transition.

Utilities and merchant developers have announced “hydrogen-ready” projects in at least 18 states in the past several years, running the gamut from technology demonstrations to large-scale commercial developments (see the appendix for the complete list). But the reality is that for at least the next 10 years, any “hydrogen-capable” gas-fired power plant is going to operate almost completely, if not completely, using methane. As such, those projects should be evaluated on that basis—not some hoped-for, potentially less environmentally damaging fuel that is years from broad commercial availability.

Duke Energy’s current effort to secure regulatory approval for two simple cycle combustion turbine projects near its existing Marshall coal plant and a new combined cycle gas turbine (CCGT) at its Roxboro coal plant site is indicative. In its filings about the projects, which would total 2,260 megawatts (MW) of capacity, Duke touts the need to build “hydrogen-capable gas turbines.” But dive into the details of its application, and you find that the utility doesn’t expect to begin using any hydrogen at the new units until 2035—and even then only at the miniscule blending rate beginning at 1% hydrogen/99% methane.

Duke’s projects, and the others being proposed today, are nothing more than traditional gas plants with environmentally friendly verbiage. State regulators and the financial community need to evaluate them on that basis.

In the body of this report, we will examine three key hurdles that will slow and perhaps entirely halt the widespread use of hydrogen as a replacement for methane in turbine generators. These hurdles are:

- Lack of supply. The U.S. produces about 10 million tons of hydrogen every year, virtually all of which is consumed in the petrochemical and fertilizer sectors. Any hydrogen blending in the power sector would require new production, and a lot of it. As the table on page 10 shows, just running the 15 largest methane-fired CCGT plants with hydrogen would require doubling current U.S. production and would replace less than 10% of the electricity now generated annually from methane.

- Lack of pipeline infrastructure. Getting hydrogen to power plants would require the construction of thousands of miles of new pipelines.

- Lack of storage capacity. The gas industry is reliable because of the vast network of underground storage facilities spread around the country; there is no comparable hydrogen storage infrastructure. Building that infrastructure would be costly and time-consuming, with many questions still unanswered regarding the safety of storing hydrogen, particularly in depleted oil and gas fields that account for the bulk of current methane storage.

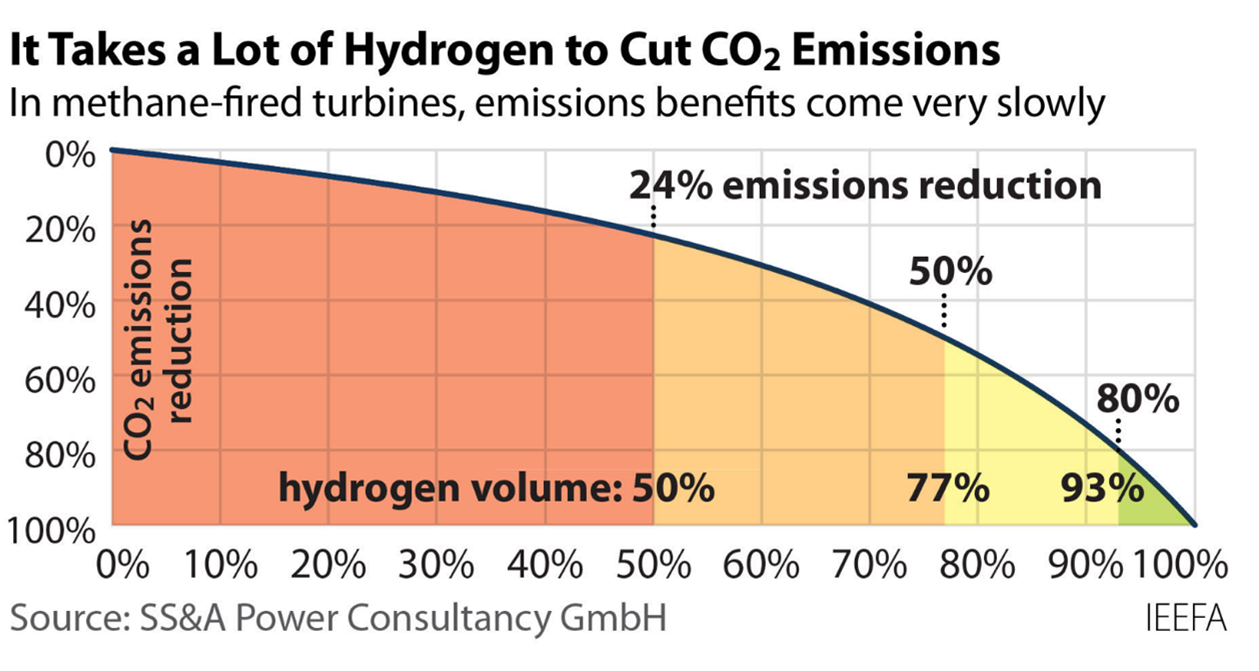

In evaluating these three massive infrastructure issues, it is essential to keep another key problem in mind: Hydrogen provides only marginal benefits in cutting carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions until very high levels are blended into the methane, as the graphic below illustrates. At low hydrogen blending levels, the infrastructure costs would vastly outweigh any environmental benefit. At the other extreme, blending high levels of green hydrogen into methane would consume vast amounts of renewable energy that would be better used directly to replace existing fossil fuel generation.

Hydrogen has other environmental problems as well. It produces high levels of nitrogen oxides (NOx) during combustion. This could have a significant impact on local air pollution unless the emissions are controlled, which would require costly controls. Hydrogen also has an indirect impact on climate change that is the subject of continued research. One recent peer-reviewed paper indicated that hydrogen’s global warming potential is 11.6 times stronger than CO2 over a 100-year time frame when accounting for impacts on other gases (compared to 28 times for methane).

Given the problems associated with using hydrogen in methane-fired power plants, IEEFA has these recommendations for regulators:

- Utilities should be required to pay for any additional costs associated with building “hydrogen-ready” turbines rather than passing those costs to consumers. It is unlikely that hydrogen will play a significant role replacing methane in turbine-fired electricity generation. Capital dollars spent by utilities on hydrogen adaptability now will simply enable them to earn a return on their investment, benefiting their shareholders at the expense of consumers.

- Utilities should be required to disclose potential additional costs associated with any “hydrogen-ready” claims, particularly regarding fuel delivery. What will a dedicated pipeline cost? Can it be permitted? How long will it take to build?

- Utilities should be required to provide details on fuel sourcing. What company will produce the hydrogen? Will it be carbon-free?

- Utilities should be required to complete a full analysis comparing the costs of any hydrogen plans with options involving zero-carbon resources, including efficiency options and virtual power plants, as well as wind, solar and battery storage.

Although aimed at regulators, these questions are equally relevant for the financial community. Funding arranged now will be paying for the construction of a methane-fired power plant, and the risks associated with that decision should be factored into every financing decision.

Figure ES-: Lots of Carbon-Free Hydrogen Required for Small CO2 Reductions