Coal use at U.S. power plants continues downward spiral; full impact on mines to be felt in 2024

Key Findings

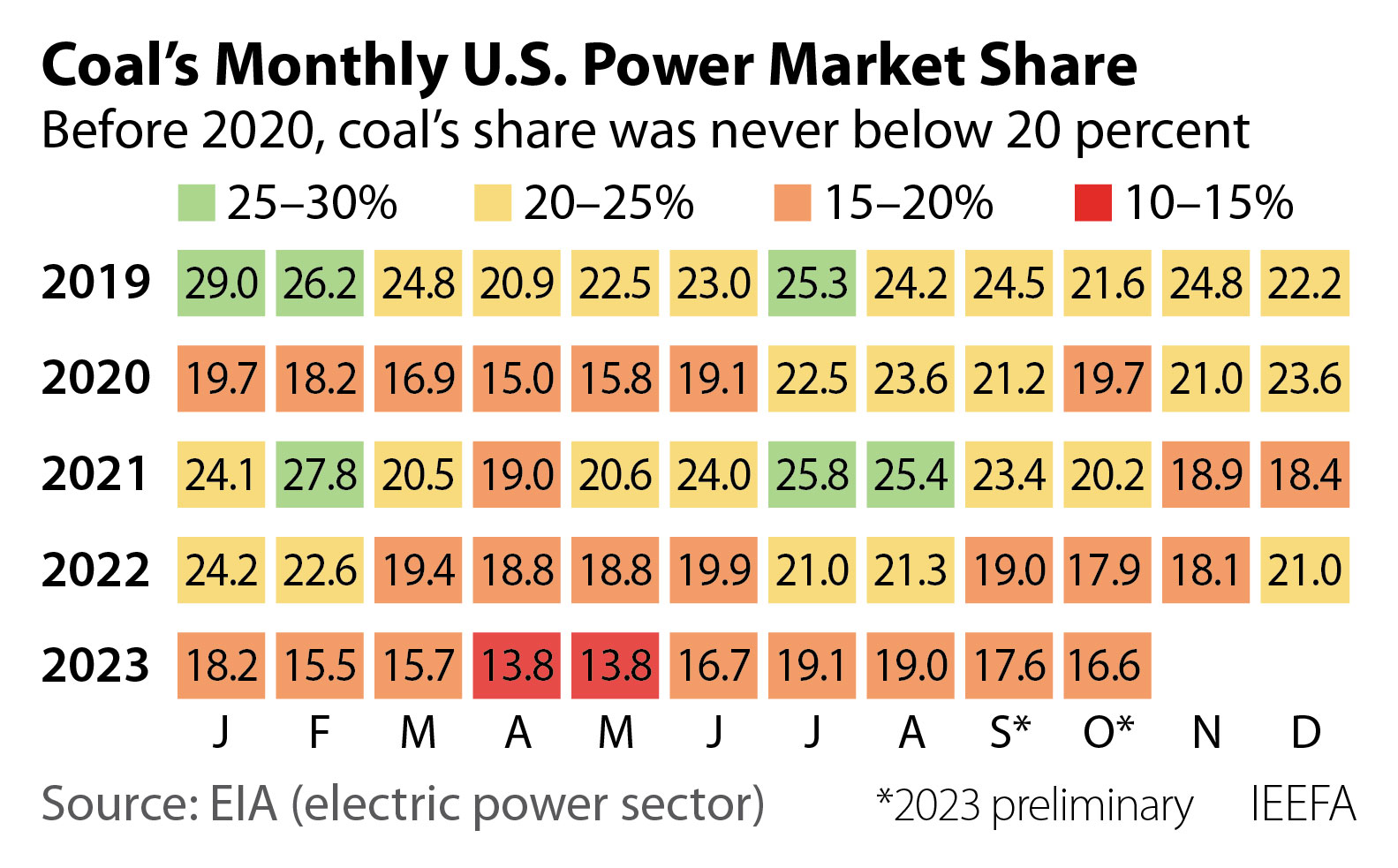

Coal use at U.S. power plants is slumping: The fuel has not achieved a 20% market share in any month so far in 2023 and the current outlook predicts low levels for the rest of the year.

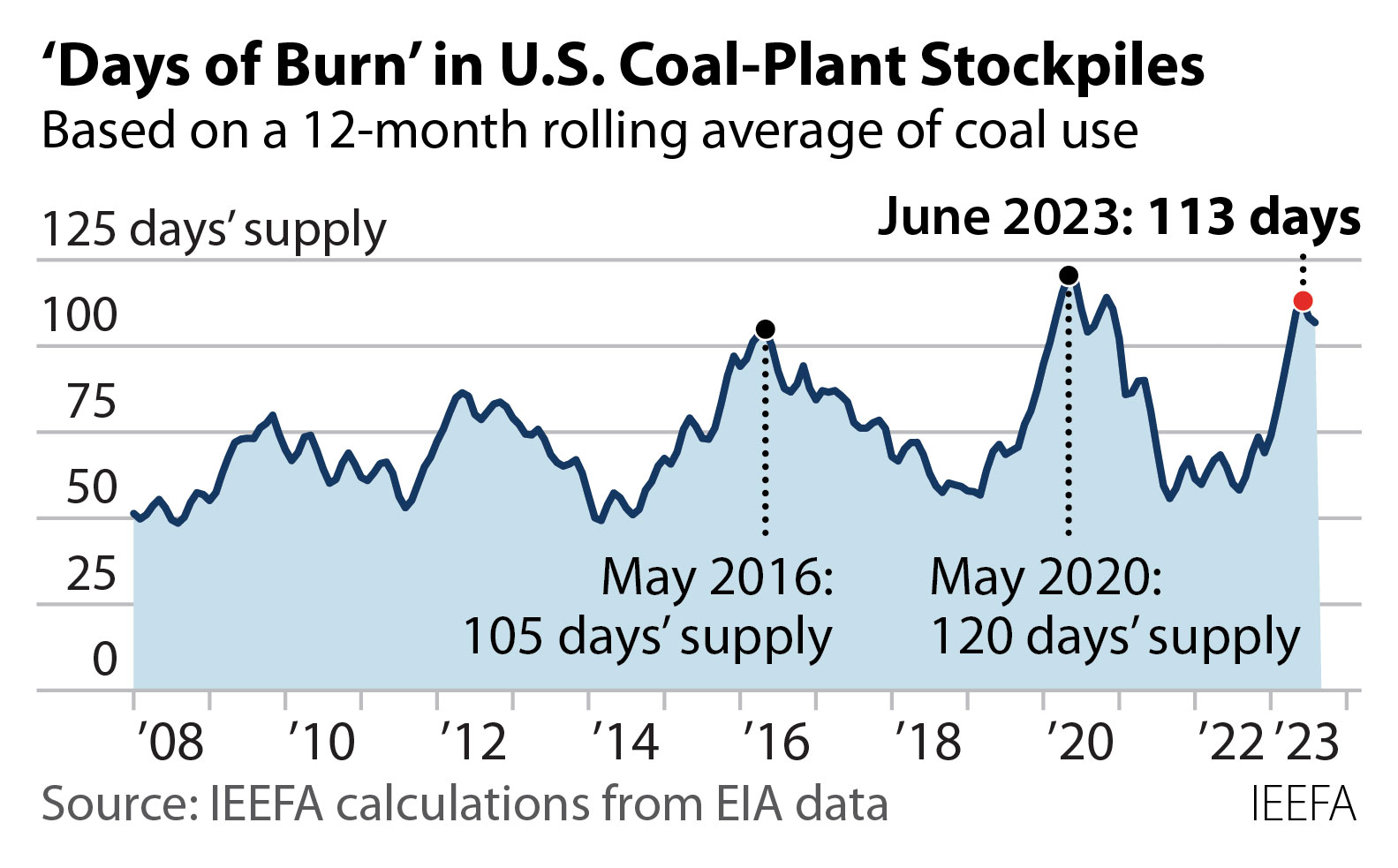

Coal stockpiles have surged to nearly 130 million tons in June—enough to run coal plants for 113 days, or nearly four months, based on the average amount of coal used over the previous year.

The amount of coal used each day in the U.S. has fallen from about 2.8 million tons a day in 2008 to about 1.1 million tons a day this year—a 62% drop.

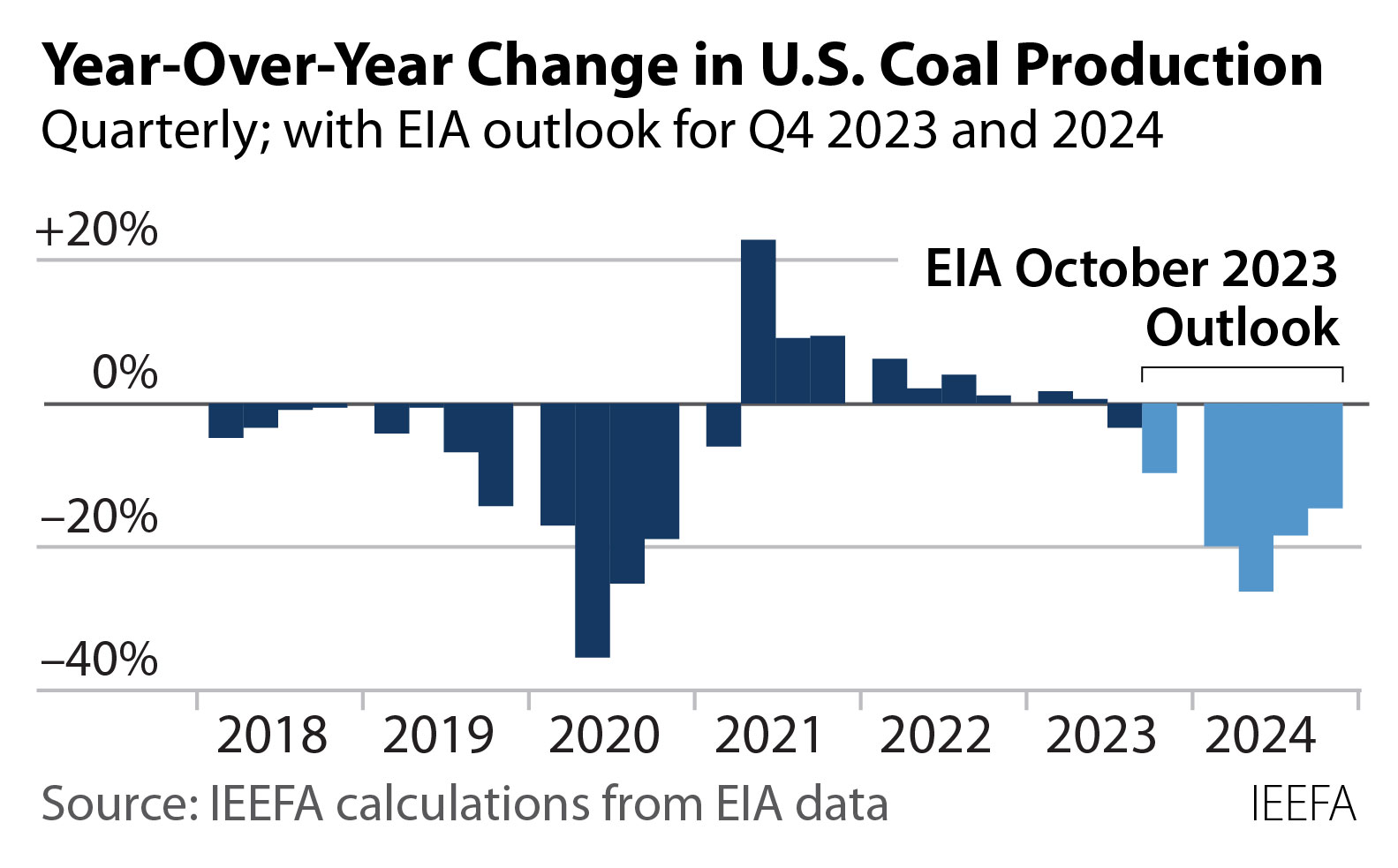

A temporary reprieve in declining coal mine production has ended—coal companies are now staring at a substantial new downturn driven by an accelerating decline in domestic demand.

This year, the use of coal by the U.S.’s power producers has been so anemic that the fuel has not achieved a 20% market share in any month so far, and the current outlook predicts low levels for the rest of the year. To put that into perspective, coal’s power market share had never been less than 20% in any month before 2020, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

In July 2023, for example, coal hit its high point for the year so far, providing 19.1% of the country’s power; in August its market share was 19.0%. That performance stands in stark contrast to 2021, when coal’s market share in both July and August was more than 25%—roughly 6 percentage points higher. The low point this spring occurred in April and May, between the winter heating and summer cooling seasons, when coal’s market share slumped to just 13.8%—the first time it has ever fallen below 15%.

Despite hotter summer temperatures and increased power demand to run air conditioning in some parts of the country this summer, the use of coal has fallen. This is a result of lower prices for gas—coal’s primary fossil-fuel competitor—and a surge in utility-scale solar generation, which was up 20% in July from July 2022, and up 23% in August from a year ago.

The EIA’s current outlook suggests even more deterioration for coal power in the coming months. The energy agency not only sees coal’s November market share returning to the record-low market share in the spring, but also dropping even more in 2024, to as low as 10 to 13% in both the spring and fall.

The decision by plant owners to scale back their use of coal can be seen in at least two measures. First, power generation at coal plants has fallen every single month in 2023 compared to the same months in 2022, both at those owned by utilities and those owned by independent power producers (IPPs)—and by a lot. Through August, utility coal generation has dropped an average of 19.7%. At IPP coal plants, which are more sensitive to competitive pressures, generation has fallen even more—declining an average of 29.7%, a sign that the economics of selling coal-fired power have deteriorated significantly this year.

At the same time, coal stockpiles have surged, to almost 130 million tons in June, and remain high. That’s enough to run coal plants for 113 days, or almost four months, based on the average amount of coal used over the previous year. This measure, called “days of burn,” is more useful than simply looking at the size of the coal piles, since there are fewer coal plants than in the past, and the ones that are still operating are running less. In fact, the amount of coal used each day in the U.S. has fallen from about 2.8 million tons a day in 2008 to roughly 1.1 million tons a day this year—a 62% drop.

It can take a long time to bring such large stockpiles down to levels power producers are more comfortable with—historically around 50 to 60 days’ supply. It took 16 months to lower stockpiles from the May 2020 peak of 120 days of burn, and it took 34 months—almost three years— to lower stockpiles after a May 2016 peak of 105 days of burn. The speed of the drawdown will also be influenced by other factors like warm winter weather, the health of the U.S. economy, and gas prices.

To cut stockpiles, coal-plant owners are likely to turn to a straightforward solution: Buy less coal.

That, of course, would directly affect coal mining in the U.S., and the EIA is already warning that a significant production downturn is coming for the remainder of 2023 and throughout 2024. Overall, coal output could fall to 466 million tons in 2024, a 25 percent decline of 115 million tons from 2023 levels, the EIA says. If that figure holds, it would be the smallest annual U.S. coal production since 1962—but most of the years between 1936 and 1957 also had higher output.

Western producers, which include the nation’s largest mines in the Powder River Basin, could be hardest hit. The EIA is anticipating output in the region to slump 30% next year, or 73 million tons, to just 246 million tons. That would be the region’s lowest production in at least 40 years. Appalachian production doesn’t fare much better. There, the EIA expects production to fall almost 22%, or 29 million tons, to just 132 million tons. For comparison, when coal output in Appalachia peaked in 1990, almost four times as much of the fuel was mined.

After a sharp drop in coal demand in 2020 due to the pandemic, output from U.S. coal producers moderately rebounded and stabilized in 2021. Then, in 2022, coal prices soared after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which broadly improved the financial health of U.S. coal companies—but provided only a modest improvement in the volume of coal produced, which declined again this year.

That temporary reprieve has ended. Coal companies are now staring at a substantial new downturn driven by an accelerating decline in domestic demand.