Pakistan must rebuild Chinese investor confidence in its energy transition

Key Findings

There has been minimal foreign direct investment in Pakistan’s troubled power sector despite repeated attempts by the government to open the market and de-risk new projects.

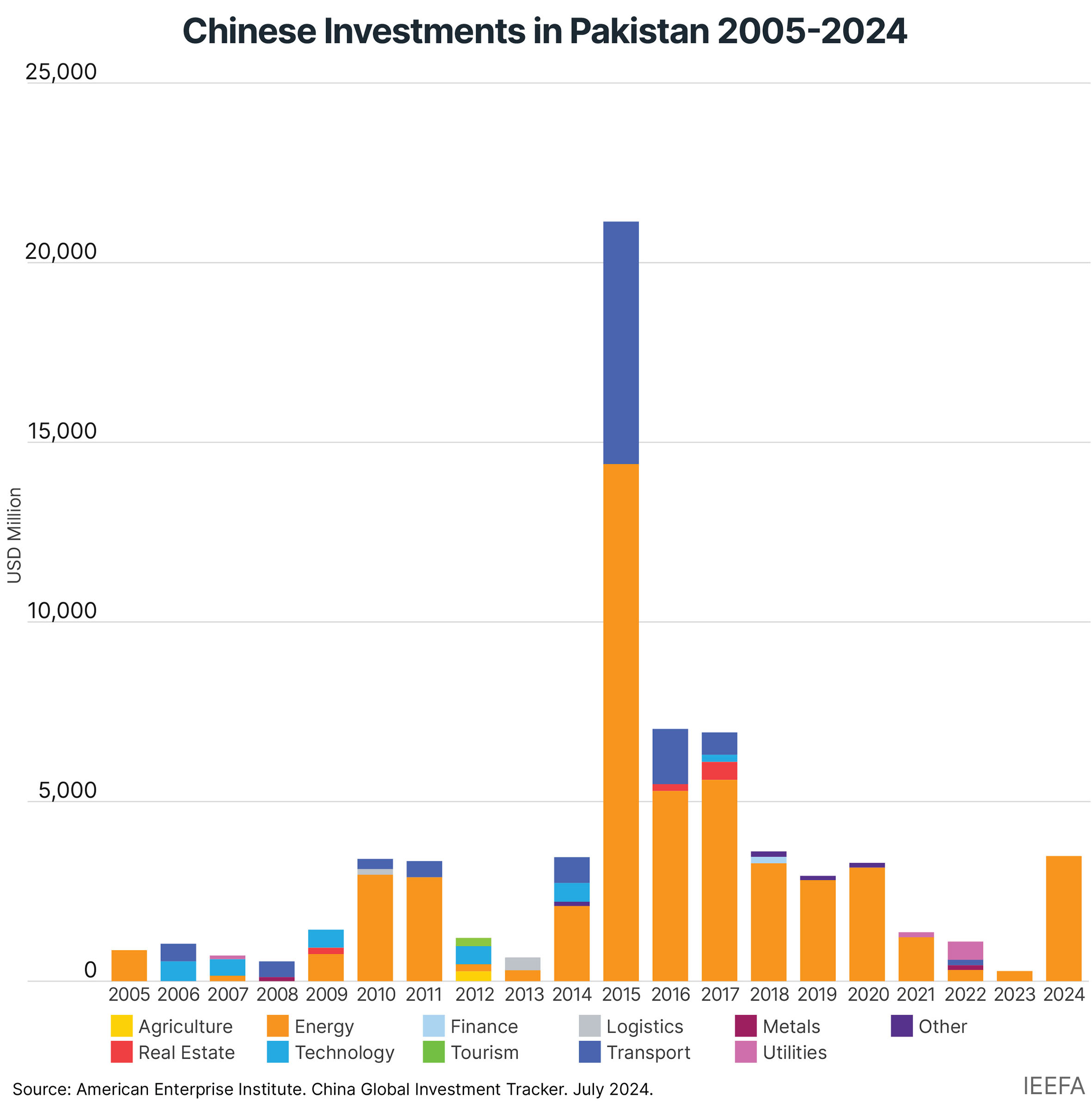

China has been Pakistan’s largest investor in the energy sector. Between 2005 and 2024, China invested almost USD68 billion (bn) in the country’s economy, with energy dominating 74% of the investment portfolio under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project.

Security concerns, lengthy permitting processes, frequent regulatory changes, and the accumulation of large arrears for CPEC power plants are some of the challenges faced by Chinese investors in Pakistan.

In the second phase of CPEC, Pakistan can benefit from China's advancements in solar PV modules, lithium-ion batteries, and electric vehicles amid tightening Western trade policies. However, success hinges on resolving security concerns, ensuring policy stability, and upholding contractual commitments.

Pakistan’s energy sector investments are on a complex trajectory. Despite government efforts to attract foreign capital and de-risk new projects, investor confidence remains low. In January 2024, a 600-megawatt (MW) solar project in Muzaffargarh failed to attract any bids. Developers cited Pakistan’s high-risk profile and political turmoil as key deterrents. Even China, a longstanding geo-strategic ally and the largest investor in Pakistan’s energy sector, showed no interest.

Between 2005 and 2024, China invested almost USD 68 billion in Pakistan’s economy, with energy dominating 74% of the investment portfolio. These investments peaked in 2015 as part of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC); a flagship project under President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative.

With an energy portfolio worth USD 21.3 billion, CPEC initially prioritised power generation projects heavily reliant on coal. Of the 13 gigawatts (GW) of power capacity added, 8 GW came from coal-fired power plants, while solar and wind energy cumulatively contributed just 1.4 GW.

Now, as CPEC enters its second phase, CPEC 2.0, unresolved issues from the first phase are slowing progress on the second.

In 2021, President Xi committed to halting greenfield investment in overseas coal projects, presenting an opportunity for cleaner energy development. However, new Chinese investments in Pakistan have faced problems recently. According to our analysis at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), since Covid only USD 4.86 billion of Chinese capital has been invested in Pakistan’s energy sector. Of this, USD 3.7 billion has been allocated to a nuclear power plant in Chashma, likely just a down-payment on a project requiring significantly more funding over time.

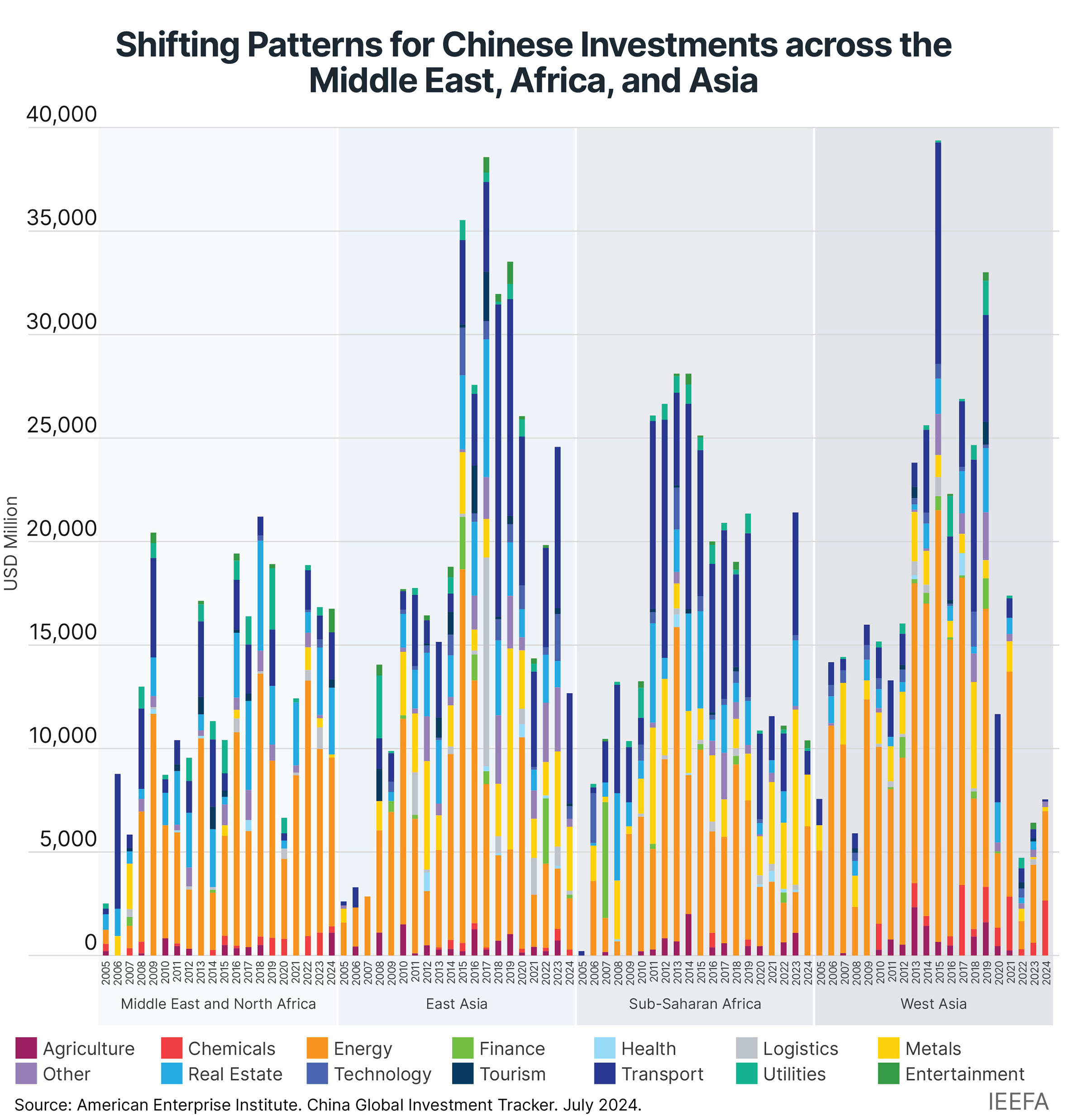

Shifting Chinese investment patterns

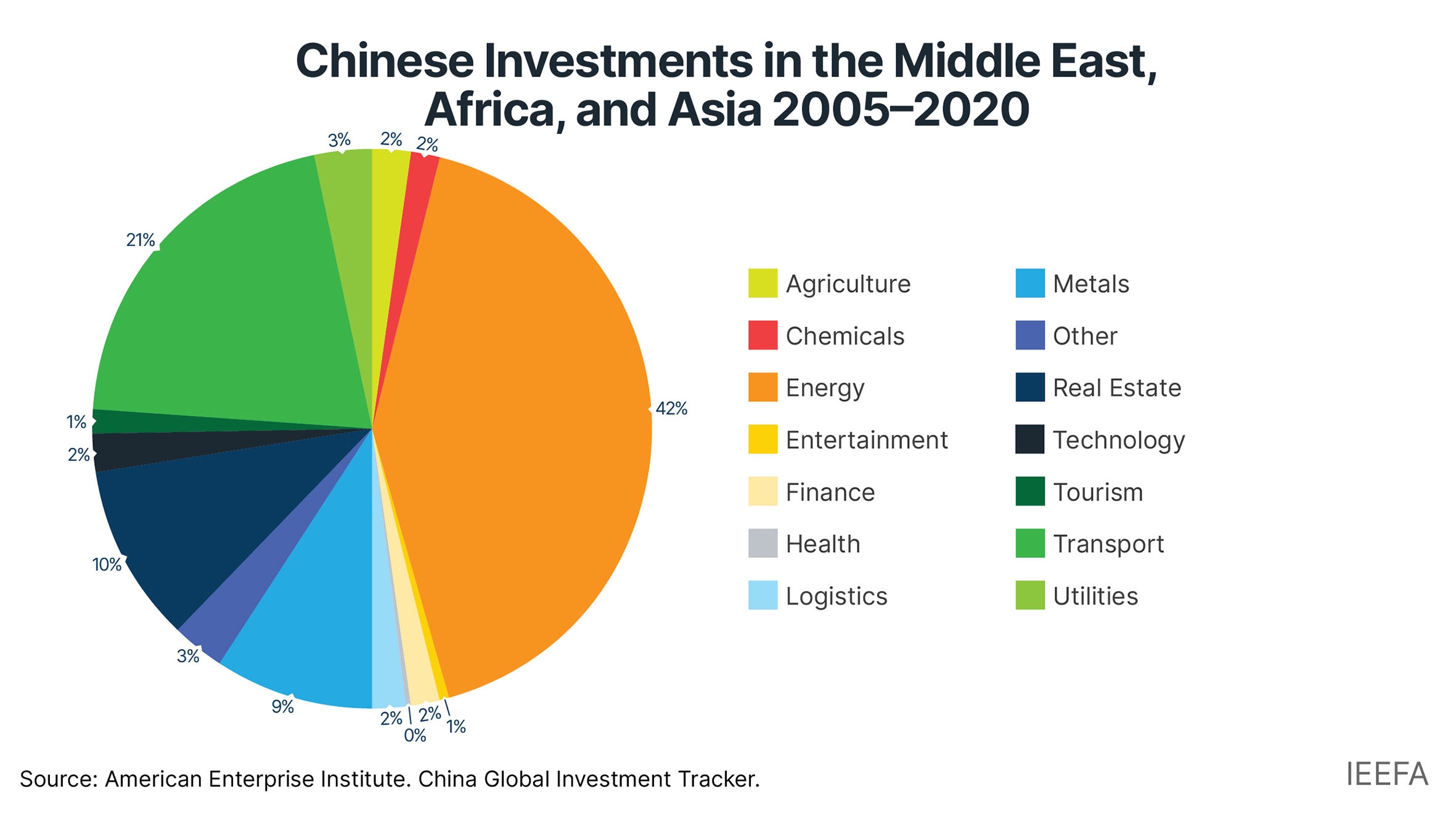

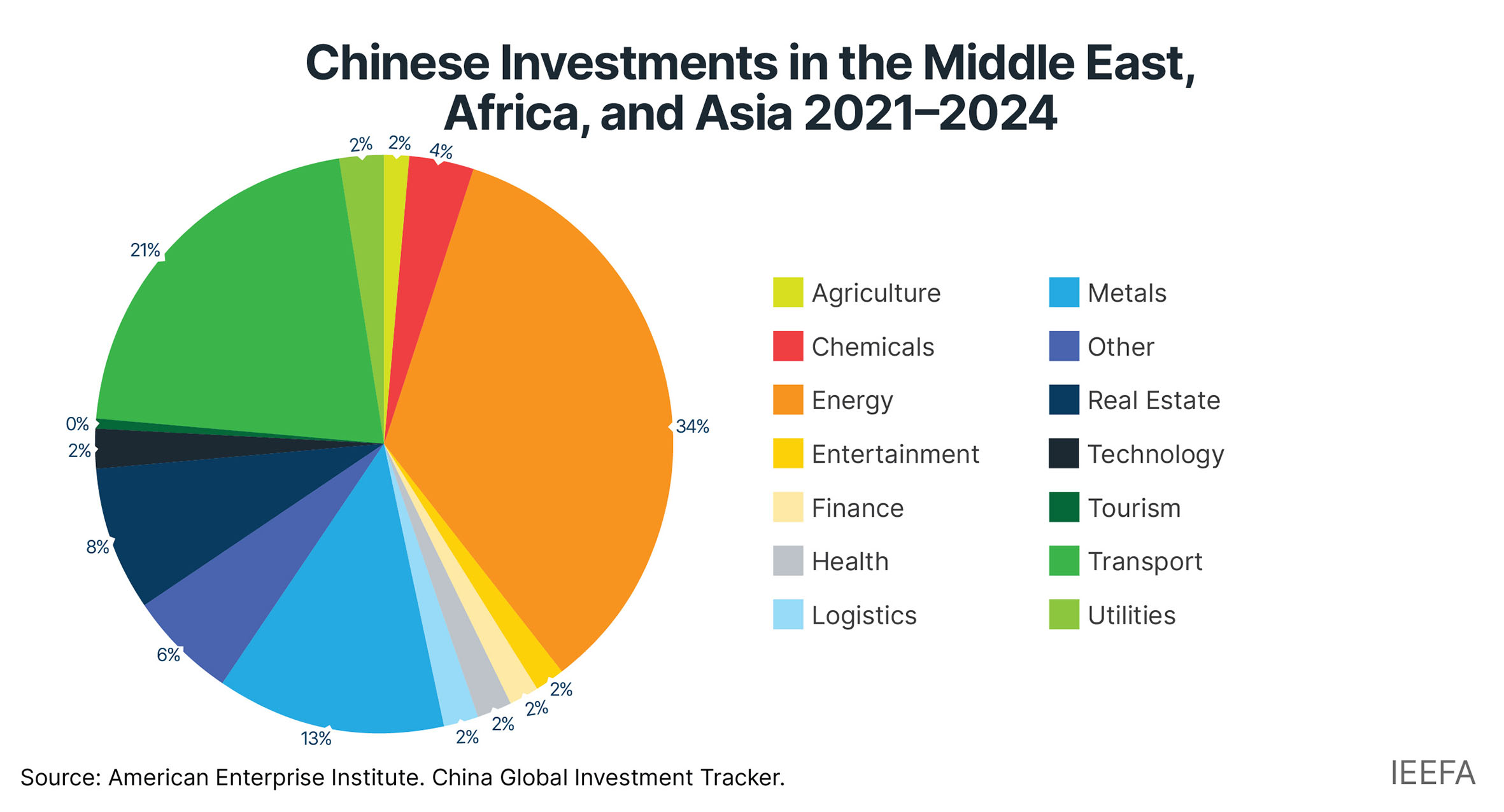

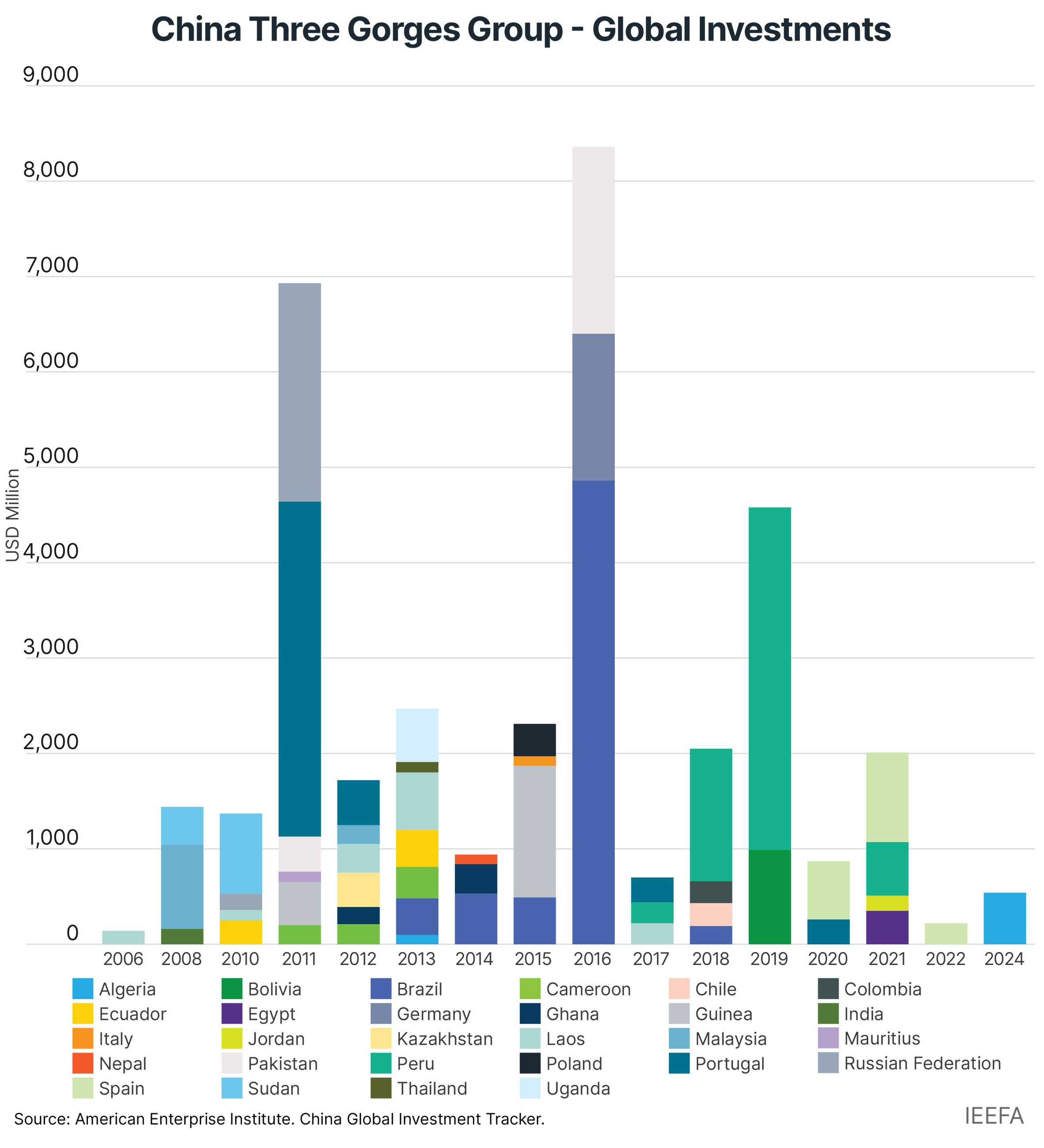

China has diversified its investment interests in recent years, reallocating capital away from Pakistan, favouring the Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa and East Africa, where post-Covid investments have resumed or surpassed pre-pandemic levels. According to the China Global Investment Tracker, between 2021 and 2024, energy investments amounted to just 34% of China’s global investment portfolio, down from 40-50% in previous years. Instead China is prioritising the metals and chemical industries, particularly in countries like Indonesia, where regulatory stability and value-added manufacturing policies have attracted investment in nickel smelting and battery production.

China’s growing interest in the Middle East reflects deepening economic ties with Gulf countries, which are seeking to diversify beyond oil-based infrastructure development. Gulf nations have welcomed Chinese expertise in infrastructure, technology and renewable energy. While China views these relationships as crucial for securing energy resources and expanding its Belt and Road footprint. Similarly, Iraq and Iran, like Pakistan, have received Chinese investments in port development and energy infrastructure.

Contrastingly, Southeast Asia has used its vast mineral reserves and industrial ambitions to attract Chinese capital. Indonesia’s export ban on unprocessed minerals forced Chinese companies to invest in local nickel smelting, boosting value-added manufacturing and strengthening its role in global supply chains for critical minerals. Various tax incentives, flexible land ownership regulations and steady economic growth have further cemented Indonesia’s appeal.

Pakistan has attempted to attract Chinese investors with tax breaks of its own, along with special economic zones (SEZs), but deeper issues persist. Industrial stagnation, high electricity and gas costs, and weak infrastructure continue to hinder competitiveness.

Investor concerns in Pakistan

Security threats remain a significant barrier to Chinese investment in Pakistan. Between 2021 and 2024, increased militant attacks targeting Chinese nationals working in the country, led Chinese firms and diplomats to call for tighter security measures. The incidents included an attack on Chinese staff from Port Qasim Power Plant in October 2024.

Even before this uptick in violence, in 2017, Pakistan’s National Electricity Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA) had introduced a security surcharge of up to 1% of total project cost, passing the additional cost onto consumers. This surcharge currently amounts to an estimated USD 216 million distributed annually, of the operational CPEC portfolio. A heavy cost one may assume, but still not adequate to prevent the loss of life.

Foreign investors also complain about lengthy permitting processes and frequent regulatory changes. Project permits require numerous approvals from various agencies, and navigating red tape leads to delays that stall progress, further discouraging investment.

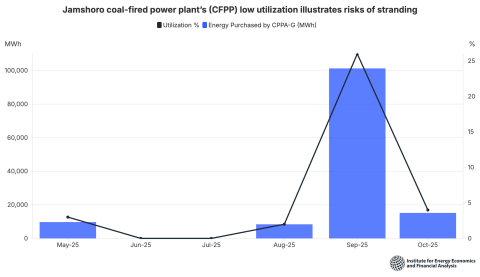

CPEC power plants in Pakistan are accumulating substantial financial arrears, with outstanding receivables reaching USD 1.4 billion. The Central Power Purchasing Agency (CPPA) has struggled to recover payments from distribution utilities, impacting liquidity and reducing the ability of project sponsors to reinvest. Fossil-fuel-based power plants are particularly vulnerable to payment delays. The Sahiwal coal-fired power plant and the Port Qasim Electric Power Company (PQEPC) have repeatedly threatened shutdowns due to non-payment. In May 2023, PQEPC served a formal default notice to CPPA for overdue payments of PKR 77.3 billion (USD 276 million). By October 2024, this figure had ballooned to PKR 88 billion (USD 315 million).

While the government periodically clears the backlog of outstanding dues, Pakistan’s structural problems will likely continue for the foreseeable future due to weak macroeconomic conditions and an inefficient electricity distribution system, discouraging new investment.

For example, the China Three Gorges Group was once Pakistan’s largest clean energy investor. It’s portfolio included three wind farms (150 MW capacity) and the Karot hydropower project (720 MW). But the group has not reinvested since 2016. Instead, its South Asian investment arm, China Three Gorges South Asia Investment Limited (CSAIL), has shifted focus to Egypt and Jordan, where it recently installed 400 MW of solar and wind projects.

AAlthough CSAIL has two upcoming hydropower projects in Pakistan – the 1,124 MW Kohala and the 640 MW Mahl projects – progress remains slow. The Kohala project has secured initial approvals but lacks authorisation from Sinosure, China’s state-owned export credit insurer, which covers investor losses in case of a default. Moreover, the Pakistan government’s recent decision to exclude these projects from its energy generation planning has further dampened investor enthusiasm.

Such regulatory challenges pose an uncertain future for pending and new investments in the energy sector and highlight an urgent need for policy realignment. Given Pakistan’s current struggle with excess power generation capacity, it may be prudent to diverge from investing in the energy sector for the present and focus on de-risking other avenues for new financing.

What will CPEC 2.0 look like?

CPEC’s first phase prioritised extensive infrastructure and power generation. The second phase, CPEC 2.0, aims to develop industrialisation, agriculture, and technology transfer through SEZs. Pakistan could benefit from China’s advancements in clean energy and electric mobility, especially as Western markets impose trade restrictions on Chinese exports. A recent meeting between the presidents of Pakistan and China in Beijing reaffirmed their commitment to further bilateral cooperation under CPEC 2.0 and mutual support on issues of core interest. However, unless Pakistan resolves its security risks, ensures policy stability and honours contractual obligations, it will struggle to attract further investment. Unlike the Middle East and Southeast Asia, which offer greater regulatory predictability and economic stability, Pakistan must work harder to rebuild investor confidence.