Australia’s coalmine methane mirage: The urgent need for accurate emissions reporting

Key Findings

Major coalminers in NSW reported lower methane emissions after updating reporting methods.

Australia’s open-cut coalminers do not measure their methane emissions directly, relying instead on one of three methods to estimate them.

There are multiple opportunities to improve the available estimation methods in Australia’s National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (NGER) scheme.

The first emissions reporting under the reformed Safeguard Mechanism from Australia’s Clean Energy Regulator (CER) reveal a contradictory trend in the coalmining sector.

On the surface, the coalmine sector’s Scope 1 (direct) emissions in the CER’s Safeguard Mechanism reporting for FY2023-24 were unchanged from the prior year at 31.6 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e). Volume-led increases in open-cut mines were offset by lower production volumes from emissions-intensive underground coalmines.

Underground coalmine production across Queensland and NSW fell by 10.6% in FY2023-24, causing an 8.5% decline in underground coalmine Scope 1 emissions.

Overall coal production grew in 2024 yet coalmine emissions were static, in line with a long-term trend highlighted in a recent report by Ember. It found that while coal production has tripled since the 1990s, emissions reported by the industry have flatlined.

This counterintuitive result stems from shifts in production methods towards open-cut operations and the chosen method of reporting emissions. The governing NGER regulations aim to resolve this, with potentially far-reaching consequences for the industry’s carbon liabilities and net-zero ambitions.

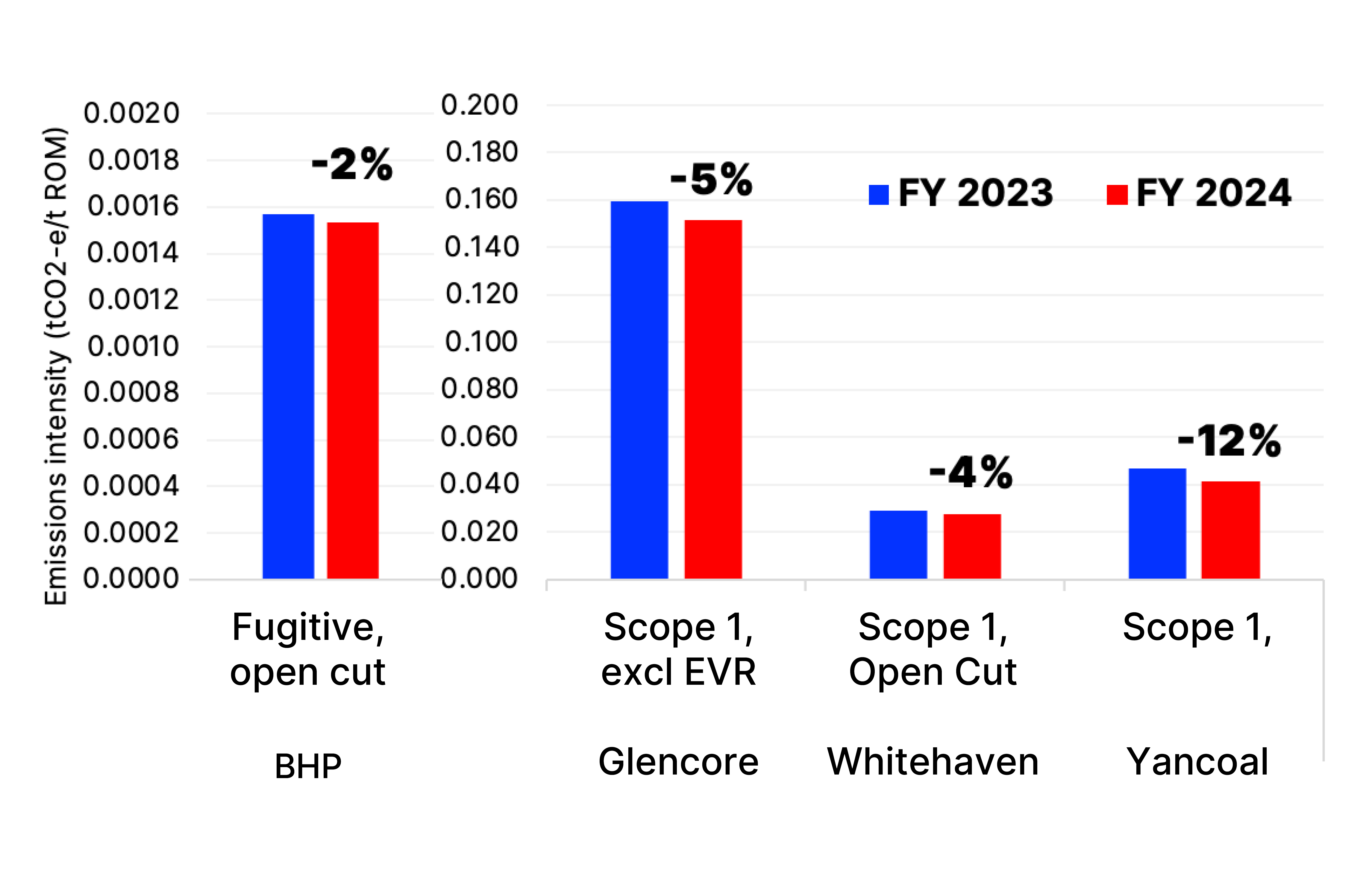

Major miners including BHP, Glencore, Whitehaven and Yancoal have all reported decreasing emissions intensities from their open-cut operations, creating an impression of environmental progress despite increased production (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Reported emissions intensity – major coalminers (tCO2e/t ROM*)

Source: Company annual reports. Note: *Tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per tonne of run-of-mine coal produced. Only BHP separately reports fugitive emissions by mine; all others report total Scope 1 emissions. BHP (Mt Arthur, Peak Downs, Saraji and Caval Ridge) and Whitehaven (Maules Creek, Tarrawonga and Werris Creek) mines. Glencore and Yancoal report all mines in aggregate.

This apparent success story masks a critical issue – significant uncertainty in how fugitive methane emissions from open-cut mines are reported. Unlike in underground coalmines, gas emissions are not directly measured from open-cut coal mines. Instead, the gas in the ground around the coalmining footprint is estimated as a proxy for what will be released when the coal is mined.

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) recently moved to phase out Method 1 reporting for large miners from FY2026-27, following recommendations from the Climate Change Authority. (Method 1 has been the default method of estimating coalmine emissions based on state average, benchmark levels.)

The review also recommended, “as a matter of urgency, review Method 2 with respect to sampling requirements and standards”. It found the sampling requirements misrepresented real mine emissions. The major coalminers in Australia – BHP, Glencore and Whitehaven – have confirmed they have switched to Method 2 reporting for all open-cut facilities, except Whitehaven’s Blackwater mine in Queensland. (Method 2 relies on self-assessed gas sampling and analysis.)

Method 2 outcomes at state level

All open-cut mines in NSW have moved to Method 2, and some have dramatically reduced their reported emissions by doing so. In Queensland, about half of its open-cut coalmines have moved to Method 2, with a further 17 required to do so in coming years. (Method 3 has higher levels of assurance but is not used.)

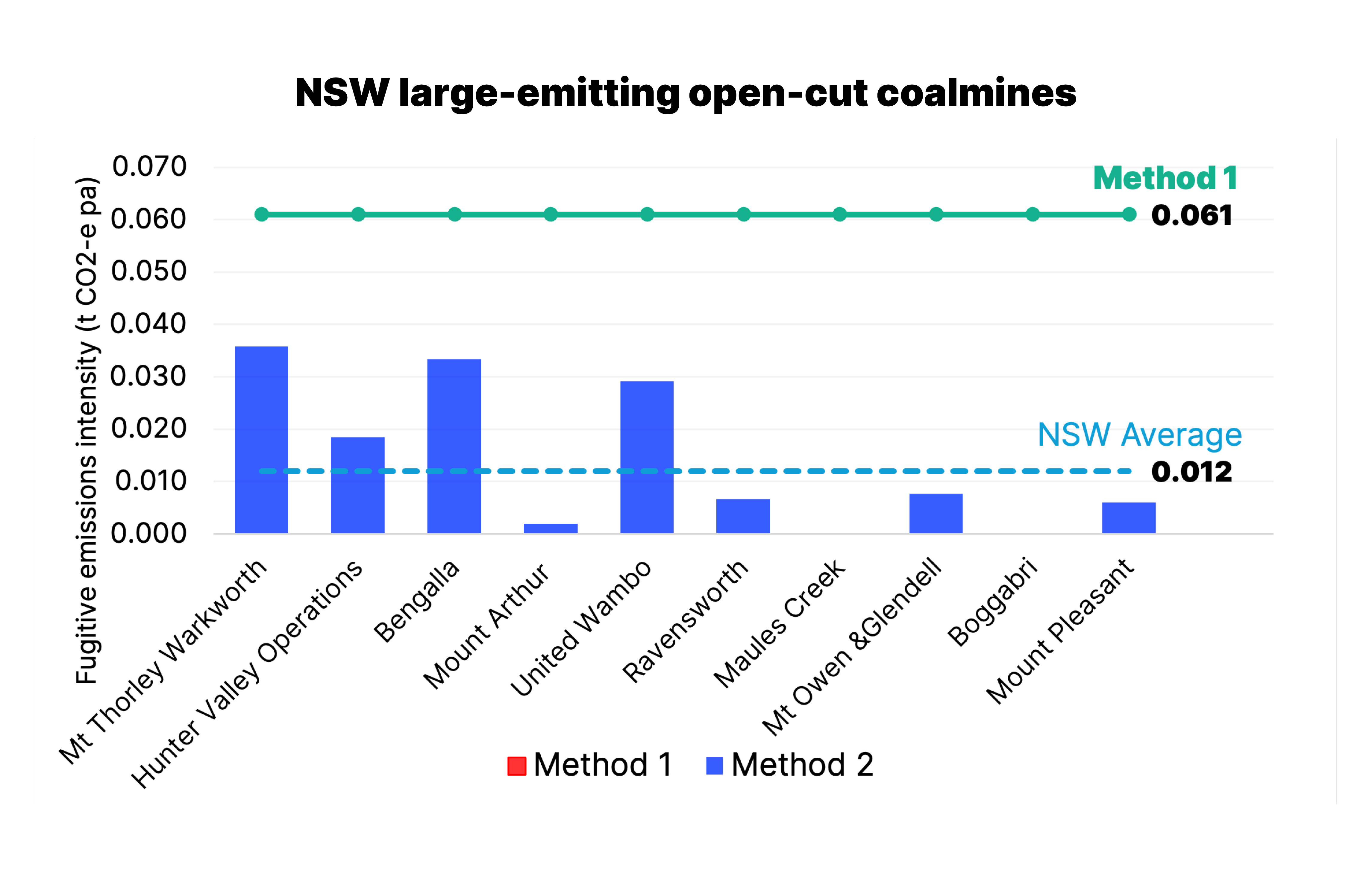

Under Method 2, the reported methane emissions intensity rates for large mines across NSW have fallen dramatically (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Method 2 actual reported methane emissions intensity vs Method 1 standards

Sources: Clean Energy Regulator, IEEFA

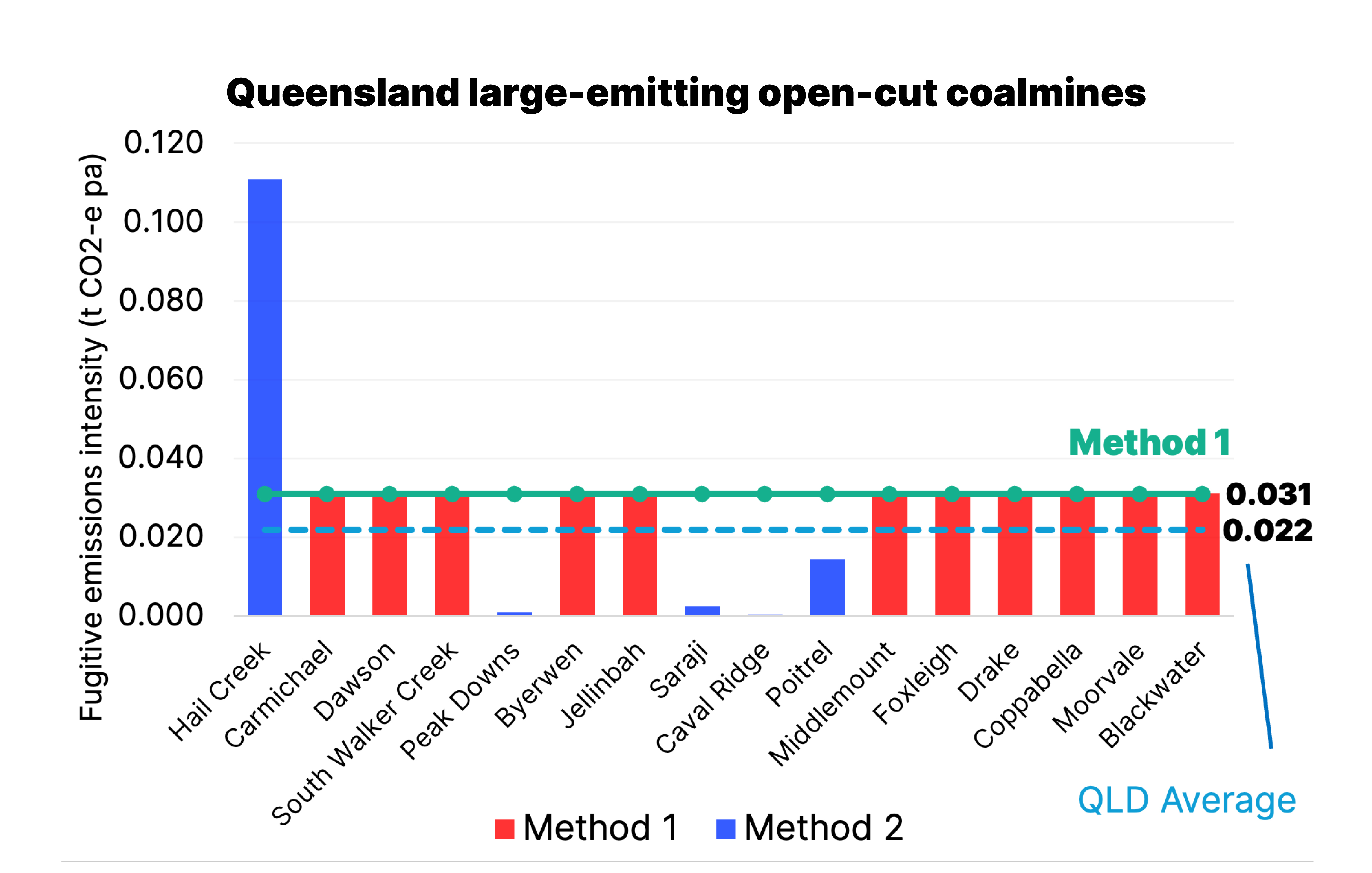

In NSW, reported methane emissions per unit of coal produced are 80% lower under Method 2 estimations compared with Method 1 default factors, based on the FY2023-24 Safeguard Facility data. In Queensland, they were 38% lower.

There is a curious discrepancy between the states. In Queensland, only half of open-cut coalmines have moved to Method 2. Only one mine – Hail Creek – has reported increased emissions from doing so. Other mines, such as BMA’s Peak Downs, Saraji and Caval Ridge, have reported near-zero methane emissions.

Method 2 outcomes at mine level

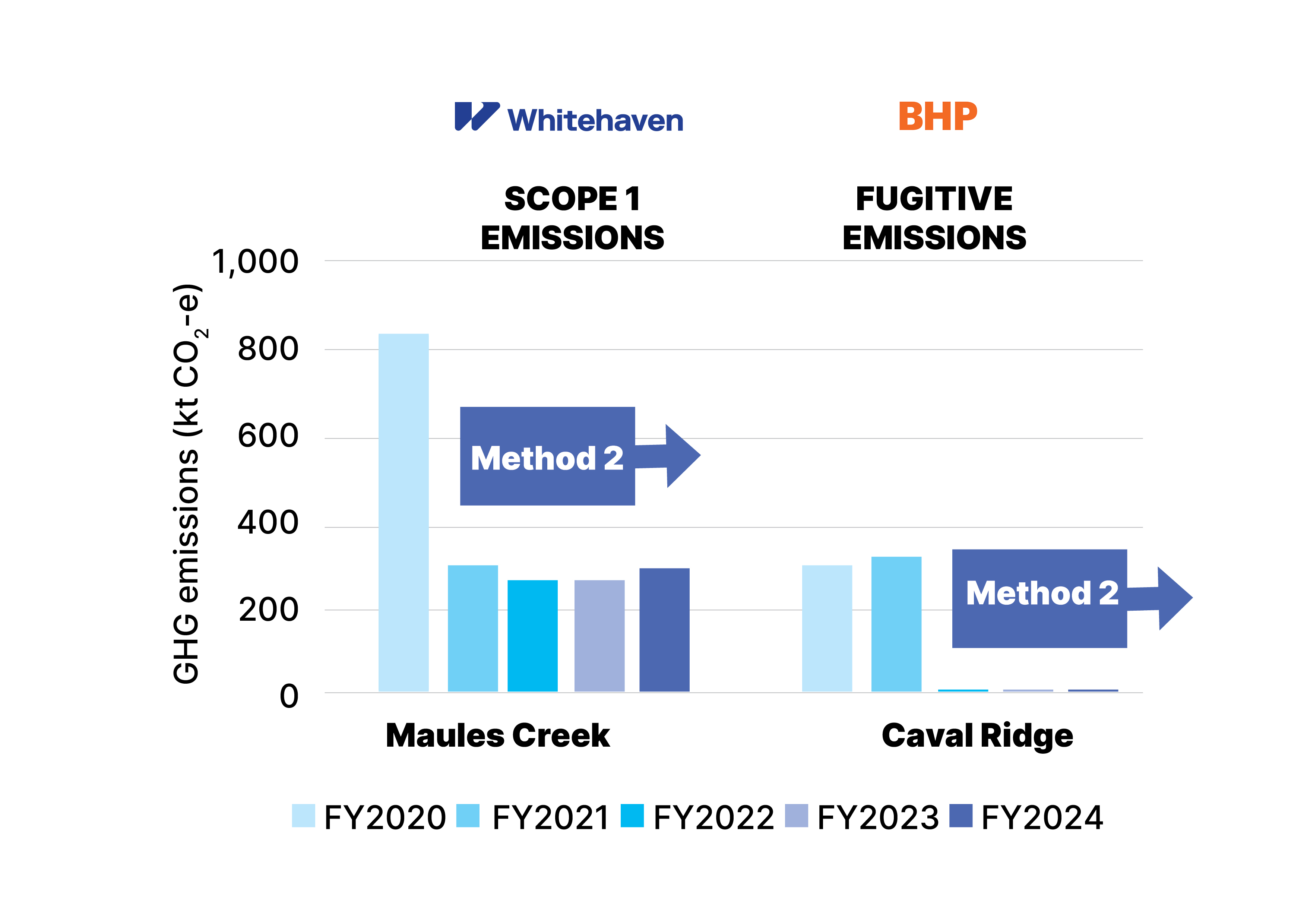

Whitehaven and BHP’s reported emissions from mines that have switched to Method 2 during the past five years fell dramatically. For example, reported emissions for the Caval Ridge and Maules Creek mines dropped by 90% and 60%, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Changes to reported fugitive emissions intensity, Method 1 vs Method 2 (tCO2e/tROM)

Sources: BHP and Whitehaven sustainability reports. Note: Shows emissions reported based on 100% operational ownership. Caval Ridge is operated by BMA with 50% equity from BHP.

Glencore stated in its 2024 annual report, “During 2024, we transitioned three of our open-cut mines (Hail Creek, Clermont and Collinsville) to the most accurate regulated method available in Australia for open-cut fugitive emissions measurement, Method 2.” despite Method 3, which is the highest order method available in the NGER scheme, not being used.

Glencore’s Hail Creek mine reported increased methane emissions from the switch, by more than 3.5 times to 0.111tCO2e/tROM. This result is not surprising, given that this mine has been the subject of recent research by the International Methane Emissions Observatory and the University of NSW. They used aerial surveys to measure methane being emitted from the mine. It was the first study to use high-resolution top-down verification of methane. They observed emissions, which, if extrapolated over an entire year, could be three to eight times greater than reported for FY2022-23.

A further study by the University of Queensland’s Gas & Energy Transition Research Centre estimated methane emissions from open-cut coalmines in the Bowen Basin. It found coal-seam gas content typically ranged from 5-12 cubic metres per coal tonne (m3/t) of coal for surface mines. This is far higher than the default value of 1.21m3/t for Method 1, implying significant under-reporting of methane emissions using Method 1.

Challenging the paradigm

The Safeguard data reveals Bowen Basin mines all reporting vastly different methane emissions intensities. Hail Creek reports 3.5x higher than Method 1. The BMA mines (Peak Downs, Saraji and Caval Ridge) reported average emissions intensity 96% lower than Method 1. Many other mines are yet to make the switch.

South Walker Creek continues to use Method 1, but its owner, Stanmore Resources, reported in its 2024 Sustainability Report: “By harnessing the methane that would otherwise be released as fugitive emissions, we will convert it into on-site power for the mine.” It confirmed sufficient methane gas is present to fuel a 20 megawatt (MW) power station for 15 years.

Whether the scientific studies and these anomaly results will be sufficient to challenge the notion that open-cut mines contain only negligible gas remains to be seen.

The issuance of Safeguard Mechanism Credits (SMCs) to Adani’s Carmichael coalmine in Queensland represents a noteworthy development in Australia’s carbon reduction framework. Using Method 1, this thermal coalmine earnt 351,232 SMCs worth $12.3 million (at an assumed $35/t) for operating below its assigned baseline in FY2023-24. That it could earn these credits without undertaking activities to reduce emissions points to vulnerabilities in the scheme.

Issues with Method 2

At BHP’s Mount Arthur mine in NSW, the methane intensity rate reported is 0.0019 (tCO2e/tROM) or 97% below the Method 1 factor of 0.061. In 2023, BHP applied to extend mining at Mount Arthur to 2030 under Modification 2. NSW Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) correspondence noted that the gas model BHP used should be adjusted to a higher rate of methane, at a fugitive emission factor of 0.00398, if correcting for nitrogen present in gas samples. Although an increase on the current mine emissions rate reported, it remains 93% below the Method 1 factor. The NSW EPA, after considering expert advice, concluded that it “cannot be confident that the revised fugitive emissions provide a suitable estimate for Modification 2”. Nonetheless, the extension was approved on 16 April 2025, with a condition that the gas model be updated and a Greenhouse Gas Mitigation Plan be prepared.

The Hunter Valley Operations (HVO) mine reports methane emissions intensity 70% lower than Method 1. It is also planning a mine extension (North Modification 8), whose greenhouse gas assessment reveals near-zero levels of emissions in the mining area.

In July 2024, the independent expert advisory panel for mining provided advice to the NSW government on the HVO Continuation Project. It highlighted accuracy risks associated with the Method 2 approach to fugitive gas estimation used in the Hunter Valley North “Domain 2 low gas zone”:

- Nitrogen was found in the reported gas test results – which could indicate potential contamination of test samples, and potentially underreporting of methane gas levels.

- Additional gas sample(s) were warranted in the low gas zone, due to samples having come from affected coal adjacent to a dyke.

Research by the University of Wollongong found the Method 2 approach to determining such “low-gas zones” flawed. This is due to the standards containing an artificially high gas detection threshold and an associated low amount of gas assumed for the low-gas zone, effectively underreporting gas considerably. This is most pronounced when high levels of methane are found in the gas (due to gas density differences). The study recommended lowering the threshold gas factor used in Method 2 by an order of magnitude.

Opportunities for improvement

Miners get to choose how they measure methane emissions and how they model the gas coming from their coalmines. Regulatory reporting is a misnomer. In fact, Hail Creek coalmine’s plan to control fugitive emissions falls under its Tailings Management Plan.

There are a number of changes that could be introduced relatively quickly to strengthen Method 2. The number of gas samples required could be increased – such as is the requirement under Method 3. Method 3 also requires asset level independent verification. Addressing the shortcomings with gas sampling and analysis identified by the experts is also required. Finally, verification with aerial or satellite observations would help.

Improved reporting standards can benefit many, from carbon markets to investors, financiers, governments, taxpayers and coal users. They all required verifiable emissions. Without them, carbon emissions will be reported, credited and traded with little grounding in reality.