IEEFA update: The investment rationale for fossil fuels falls apart

For decades, the fossil fuel sector literally fuelled the global economy and powered the world’s investment markets.

This is no longer the case. The long-standing and now outdated investment thesis around fossil fuels—that such holdings would make large and reliable annual contributions to institutional funds—has crumbled.

The sector now lags the broader market, and the one-time assumption that an oil and gas company’s value equalled the number of barrels of oil, or reserves, it owned has collapsed alongside the core steady-returns rationale for investing in the sector.

A new paradigm is emerging: Cash, revenue, and profits matter, and risks cannot be ignored. Fossil fuel companies are responding in different ways to this shift, some more responsibly than others. But some companies (and their investors) ignore what’s happening, and they do so at their peril.

The absence of a coherent and honest industry-wide value thesis today places fossil fuel investors at a true disadvantage. The days of powerhouse contributions by such companies to investment fund bottom lines are over. The risks of continuing to invest in coal, oil and gas are formidable and unlikely to abate.

Given the industry’s lackluster rewards and the daunting risks it faces, responsible trustees and investors must ask: “Why are we in fossil fuels at all?” (See our recent report on that question here).

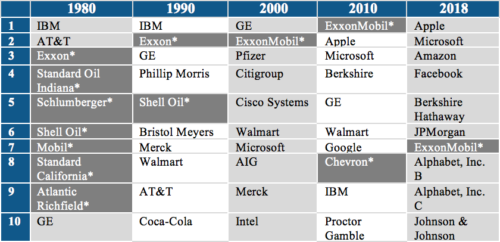

In the early 1980s, fossil fuel stocks comprised seven of the top 10 companies in the Standard and Poor’s 500 Index. Today, only one, ExxonMobil, is in that class, where it ranks seventh after having been number one as recently as 2010.

Table 1: Standard and Poor’s Top 10, 1980-2018

* Oil and Gas company. Source: https://us.spindices.com/indices/equity/sp-500

For the past five years, the energy sector has lagged almost every other industry globally. Instead of bolstering portfolio returns, energy stocks dragged them down, and investors lost billions of dollars.

Paradoxically, the fossil fuel sector’s fall was caused largely by a drop in prices that grew out of a major technological innovation: hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, which increased the supply of cheap oil and gas and emerged as a new source of supply that disrupted the dominance of OPEC. After 2014, oil prices crashed, oil company revenues plummeted, expensive capital investments failed, massive amounts of reserves were written off as no longer viable, and major bankruptcies occurred.

THE SECTOR’S DECLINE EXPOSED WEAKNESSES IN THE OLD INVESTMENT RATIONALE, part of which was built on the assumption that a company’s value was determined by the reserves it owned.

According to this thesis—one promoted by the industry and supported by many analysts and investors —oil and gas companies had to maintain an abundant portfolio of reserves, no matter the cost. These reserves would allow companies to deliver returns in any investment climate, specifically by weathering price declines that were viewed as temporary, and then profiting from relentless global economic growth that would forever spur demand for more oil and gas. Hydrocarbon reserves thus became a key metric of long-term value (see “Private Empire: Exxon Mobil and American Power,” New York: Penguin Books, 2012, pps. 186-193).

This rationale worked for decades, and, as a result, many investors assumed that new reserves, even those acquired at great cost, would ultimately yield handsome rewards.

The shale boom encouraged the oil and gas sector to double down on the reserve growth thesis, and Wall Street—long accustomed to viewing oil reserves as a key metric of financial value—bought into that mindset.

But fracking undermined the old reserve-based investment mindset in two ways. First, it rendered old estimates of total global reserves meaningless, as supplies of oil and gas were now viewed as abundant and no longer in short supply (at least not on a time frame that mattered to Wall Street).

Second, the price collapse caused by the new abundance of oil and gas actually destroyed the economic value of many reserves. Accounting rules define proven reserves in both geologic and economic terms: a reserve represents the amount of oil and gas that could be profitably extracted at expected future prices. But as expectations for future prices fell, many “reserves” were seen as suddenly unprofitable, forcing the industry to write off many of them as worthless.

As the old, reserve-focused investment thesis withered, oil and gas became just another commodity investment subject to the same short-term variables—prices, profits, cash flows, debt, dividends, and asset quality.

Cash is king now. And risk can no longer be ignored.

AS THE REWARDS OF INVESTING IN THE SECTOR HAVE DIMINISHED, RISKS HAVE RISEN—and will likely continue to rise. The sector is ill-prepared for a low-carbon future because of the many idiosyncratic factors of individual companies and an industry-wide failure to acknowledge—and plan for—the energy transition that is gaining momentum.

The global economy is shifting toward less energy-intensive models of growth, geopolitical tensions are creating near-daily volatility, fracking has driven down commodity and energy costs and prices, and renewable energy and electric vehicles are gaining market share.

Add to all that the fact that litigation on climate change and other environmental issues is expanding and campaigns in opposition to fossil fuels have matured. Such forces are now a material risk to the fossil fuel sector and an argument unto themselves for the reallocation of capital to renewable energy and electric vehicles.

These risks, taken cumulatively, indicate that the old investment rationale for investing in the coal, oil and gas sector has lost its validity. Successful investing in these industries now requires deep expertise, strong judgment, a hefty appetite for risk and a robust understanding of how individual companies are positioned with respect to their competitors both inside and outside the industry.

Where passive investors could once choose from a broad basket of oil and gas industry securities with little reason to fear they would lose money, that assumption no longer holds. Blue-chip stocks with stable returns are far more appealing, and—simply put— coal, oil, and gas equities are no longer worth the risk.

Tom Sanzillo is IEEFA’s director of finance. Kathy Hipple is an IEEFA financial analyst.

RELATED ITEMS:

IEEFA report: Fund trustees face growing fiduciary pressure to divest from fossil fuels

IEEFA update: New oil price volatility will help drive transition from fossil fuels

IEEFA Update: How Gas and Oil Companies Are Starting to Look Like the Yellow Pages (Remember Those?)