A sustainable financial-sector roadmap for Indonesia must aggressively incorporate rigorous environmental and social standards into the credit-risk framework.

That’s one of the core takeaways from a recent symposium sponsored by the Financial Services Authority (OJK), which is Indonesia’s chief finance-sector regulator, and the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private-sector finance arm of the World Bank. While participants at the Bali event lauded Indonesia’s four-part initiative to adopt standards to support the “four Ps:”—pro-growth, pro-jobs, pro-poor, and pro-environment—it includes directives aimed at encouraging the transition to a low-carbon economy.

That’s one of the core takeaways from a recent symposium sponsored by the Financial Services Authority (OJK), which is Indonesia’s chief finance-sector regulator, and the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private-sector finance arm of the World Bank. While participants at the Bali event lauded Indonesia’s four-part initiative to adopt standards to support the “four Ps:”—pro-growth, pro-jobs, pro-poor, and pro-environment—it includes directives aimed at encouraging the transition to a low-carbon economy.

The first step in establishing how reach a destination, of course, is to know where you’re going. On this point, the OJK and the IFC agree: Indonesia’s best interests will be served by an energy economy that will meet the country’s climate change pledges, provide a pathway to more sustainable economic growth, and build the Indonesian banking sector’s project-finance capabilities.

The Indonesian government has reiterated its commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 29 percent from business-as-usual (BAU) projections by 2030—and by 41 percent if it receives international support for this transition. The bulk of these greenhouse-gas reductions would come from forestry- and peatland-mitigating measures that would include significant reforestation initiatives and would account for about 88 percent of emission-reduction commitments. Only 5 percent would come from changes in the energy and transportation sectors.

This plan, on its face, is less than ambitious than it sounds.

According to the think tank WRI Indonesia, which has developed the Indonesia Climate Data Explorer, a tool that tracks emissions, energy-sector pollutions is on the rise today in at least 10 of the country’s 34 provinces. They include East Java, West Java, Central Java, South Sulawesi, Banten, DI Yogyakarta, the Riau Islands, North Sulawesi, Maluku and the capital province, DKI Jakarta.

If Indonesia were to adopt a proportional response to the broader economic threat posed by carbon-intensive sectors, it would be aiming now to transform its energy mix and diversify away from coal dependence.

To its credit, the Indonesian government seeks to derive 23 percent of its energy mix from renewable sources by 2025, a sizeable increase from the current percentage, which is in the low teens and comes mostly from hydro and geothermal. It cannot get there, however, unless it moves more assertively.

Here are three ways by which Indonesia can hasten its energy transition:

- By restricting funding for the dirtiest types of coal power.

This will require curtailing the dominance of coal-fired combustion technology in the power fleet and by retrofitting where appropriate to technology that emits far fewer pollutants for each unit of electricity generated.

In developing sectoral environmental and social standards to govern lending power-sector lending, OJK and Indonesian banks would do well to consider referencing new Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) guidelines governing export-credit financing for coal-fired power plants. The new rules, which came into effect Jan. 1, discourage the financing of the dirtiest coal-fired power projects.

Financing is still allowed for the most advanced “ultra-supercritical” plants, and for some other plants in the very poorest countries. Very small projects (<300MW) that use outdated subcritical technology will still be eligible for export-credit support. - By equipping domestic banks with project finance capabilities.

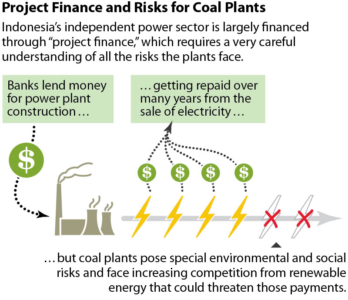

Indonesia’s independent power sector is financed today largely by international, commercial banks—mostly Japanese—through project finance deals. This arrangement excludes Indonesian banks, whose capabilities remain underdeveloped and underutilized.

Project finance is essentially a leveraged transaction in which lenders fund a substantial portion of the capital cost of establishing a new business that will construct, own and operate an asset. It is non-recourse in nature, meaning that the lender is entitled only to repayment from the revenue generated by the project the loan is funding, not from assets of the borrower. The reliability of project revenues is heavily dependent on the underlying commercial viability and appropriate risk allocation. As repayment is entirely predicated on the viability of the project, every aspect of any project finance deal needs to be bankable.

Environmental and social risks, including risks arising from climate change, will significantly alter the risk profile of new energy projects in Indonesia. Erratic weather events can disrupt power plants at every stage of a project cycle, increasingly stringent regulations on greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution and water utilization will limit the lifespan of operations, and competitive renewable energy will lower utilization rate of coal plants.

Domestic banks, being the “boots on the ground,” clearly have an advantage over outside banks. There’s also the fact that foreign- currency-denominated loans (a considerable portion of which are project finance loans made by international banks) supported about 30 percent of Indonesia’s gross domestic product as of mid-December, according to Capital Economics, which leaves the country vulnerable to an appreciating U.S. dollar.

Building domestic-bank capacity to understand the myriad of risks involved in new power projects will enable them to assign risk allocations in the best interest of project sponsors, lenders and the the electricity buyer—the state-owned utility Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN). - By requiring that environmental risk management profiles cover corporate loans.

Banks will do well also to apply broader environmental and social risk management profiles to proposals when extending corporate loans to power developers. The size of such loans are quite often determined by the capacity of the power project for which the borrower intends to use the proceeds. While this may not be “project finance,” strictly speaking, the risks associated with coal power projects loans are usually similar.

All in all, banks—domestic and foreign—play a critical role in supporting Indonesia’s drive to achieve universal electrification, and will be instrumental in directing capital toward lower-emission, affordable and accessible forms of power generation.

By increasing their capabilities in robustly assessing risk, domestic banks, especially, can cultivate new business in financing independent power projects. Such inclusion will translate into less foreign-exchange risk for Indonesia by reducing its dependence on financing through long-tenor loans denominated in U.S. dollars—and will help hasten sustainable economic growth.

Yulanda Chung is a Southeast Asia-based IEEFA energy finance consultant.

RELATED POSTS:

IEEFA Asia: Rosy Prospects in Indonesian Coal?

IEEFA Update: In Emerging Economies, New Forms of Renewable-Energy Financing Are Taking Root

IEEFA Asia: At a Crossroads, and Where Much of the Energy-Transition Action Is