IEEFA Europe: Weak Carbon Prices Are Fracturing EU Energy Policy. Here’s a Remedy.

Weakness in carbon prices—what industries are willing to pay for the right to pollute—are fracturing energy policy in Europe and hardening an East-West divide that puts regional unity and progress at risk.

The gist of the rift can be distilled in the current state of the European Union emissions trading scheme, which was supposed to reduce pollution from factories and power plants by requiring them to buy one “EU allowance” (EUA) for every ton of carbon dioxide emitted.

The 11-year-old scheme is faltering today and indeed has become increasingly irrelevant ever since the global financial crisis eight years ago, which damaged industrial output and effectively created a lingering glut in EUAs.

The program is in such limbo that EU member states last year agreed to by some 900 million EUAs and put them in a “market stability reserve” that will skim off surplus EUAs—but not until 2019 and at a rate that won’t see a return to supply-demand balance some time after 2030.

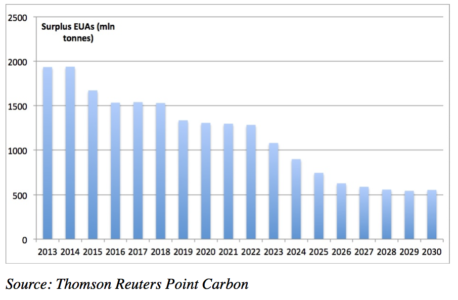

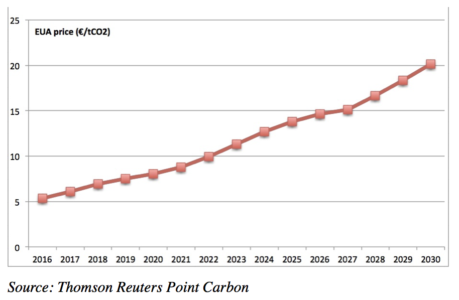

That means low carbon prices through the 2020s, which means there will be less incentive to modernize than there could be.

FIGURE 1. Forecast EUA prices, 2016-2030 (real 2015 prices)

FIGURE 2. Forecast EUA surplus, 2013-2030

Some European countries are simply taking matters into their own hands, independent of EU policy (a splintering that a referendum favouring a U.K. exit from the European Union will only make worse).

In the past 12 months, for instance, several better-off,, less coal-dependent countries in Western Europe have taken unilateral policy action to cut coal emissions. France will impose a carbon price floor (a quasi-tax on carbon) in January, and is mulling a complete coal phase-out by 2023. Britain has announced its intentions to phase out coal by 2025. Germany has introduced a limited phase-out of older lignite-fired power plants. Sweden plans to buy and retire EUAs as a way to limit their availability and increase their price, in effect making coal-fired electricity more expensive.

Meanwhile, coal-addicted countries in Eastern Europe, especially Poland, are going the opposite way. Poland is so emboldened by low carbon prices that it has mounted a well-funded campaign to defend coal, the government has urged state-controlled utilities to prop up loss-making miners, and the country is now developing nearly as much coal-fired power as the rest of the EU combined.

The growing nationalization of energy policy only thwarts progress to cut emissions and unify electricity markets, risking a disjointed, inefficient approach that would put countries at loggerheads. If, for example, French carbon-pricing policy works in France, it may only reduce broader EUA demand (and prices), making it cheaper for coal-fired generation to flourish elsewhere in Europe within the EU emissions trading scheme.

THE GOOD NEWS IS THAT A WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY TOWARD GREATER UNITY HAS JUST OPENED BY WAY OF an initiative through which the EU is embarking on a new round of changes to the directive that frames the European Union carbon market. It takes into account last year’s Paris accord on climate change.

While a pan-EU floor on carbon prices would be the best course of action, the European Commission would oppose such a move as too far-reaching. And because it would require unanimity across all 28 states, such an initiative would be dead on arrival owing to the fact that Poland would surely block it.

That leaves three realistic ways forward:

- Tweaking the rules on the market stability reserve program so that it will kick in before 2019, hastening the effects of the current plans

- Withdrawing more EUAs from circulation to reflect national coal phaseout and retirement plans

- Requiring certain egregious polluters to buy more than one EUA for each ton of carbon dioxide emissions, and in particular lignite-fired power plants.

All three options make sense and would have a collective immediate impact.

No. 3, originally proposed by Germany last year, could be especially useful. Requiring older coal- and lignite-fired power plants to pay more would accelerate plant retirements and coal phase-outs, helping Europe stay abreast of the fast-moving new global energy economy. One plus in that particular wrinkle is that it would spare from higher carbon prices industries like steel, which must compete in international markets.

By acting soon to update the EU emissions trading scheme, the European Commission would be offering much-needed leadership in a time of grave uncertainty.

Gerard Wynn is an IEEFA energy analyst.

RELATED POSTS:

IEEFA Europe: ‘Capacity Payments’ Provide a Lifeline to Costly Coal-Fired Generators

IEEFA Europe: Turkey at a Crossroads—Invest in the Old Energy Economy or the New?