IEEFA Update: A Rush to Subsidies as Power Plants in Europe Face an Existential Threat

So-called capacity markets are driving what appears to be a major new trend in energy policy across Europe: More public subsidies for electric utilities.

So-called capacity markets are driving what appears to be a major new trend in energy policy across Europe: More public subsidies for electric utilities.

Utilities may get—but not necessarily need or deserve—high-level government support for a variety of reasons, including for their role in equity markets, where they supply returns and dividends for pension funds and municipalities. This is notably true especially for RWE in Germany. Utilities are also important employers and lobbyists.

Recent examples of the kind of support we’re talking about include the proposed nationalization of long-term nuclear waste disposal liabilities in Germany; payment of some €1.6 billion for the mothballing of ageing lignite power plants (also in Germany); the reduction of property taxes on hydropower in Sweden; and, of note for its momentum and sweep, the pan-European push toward capacity payments for coal and gas-fired power.

Capacity markets reward power plants simply for being available, even before—or if—they generate any electricity, and they cost billions of euros annually in ratepayer or taxpayer-funded support. Many European countries are implementing such schemes on the rationale that traditional thermal power plants—those that burn coal or gas, for example—are under existential threat from recent growth in renewable power.

To be sure, wind and solar power have pushed conventional power plants off the grid, and contributed to lower wholesale power prices. But does this justify handing out billons of euros?

Two instructive examples come to mind: Those of Spain and Britain.

IEEFA, as it happens, has just published a report digging into the capacity market in Spain, one of the longest-running in Europe, while Britain last week disbursed £1.2 billion of ratepayers’ funds in its latest auction for capacity to be delivered in 2020.

In both cases, we think wholesale power market reforms would achieve much or exactly the same thing capacity payments do by securing grid integration of high levels of renewable power at a fraction of the cost. The potential savings amount to hundreds of millions of euros in several countries.

First, to Spain, where we note in our report—“Spain’s Capacity Market: Energy Security or Subsidy”—how the country sets the price for capacity rather than for the quantity it actually needs. Allowing a competitive auction to determine the price would achieve a true market price and eliminate the subsidized bias favoring national gas and coal and hindering the inclusion of battery storage, interconnectors and competing generation in France and Portugal. Allowing wider participation in an auction-led scheme would increase transparency and cut costs.

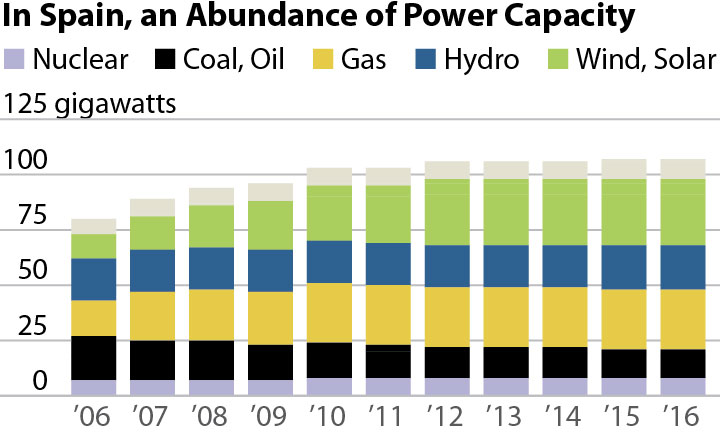

We address in our report several other flaws in the country’s electricity markets. Among them are that Spain’s electricity system is suffering from massive over-capacity, exacerbated by the capacity market itself, which has reduced returns in wholesale power markets. There are also quirks such as price caps in regular power markets, and a regulation preventing mothballing of idle power plants. Spain is lacking a powerful, independent energy regulator that could close surplus capacity, reduce or eliminate price caps, and create a less costly market.

Reforms, alongside greater efficiencies in Spain’s capacity scheme, would greatly reduce and maybe eliminate capacity payments, presently costing the country about €1 billion annually.

MEANWHILE, THE U.K. LAST WEEK COMPLETED ITS LAST AUCTION FOR GENERATING CAPACITY FOUR YEARS OUT, contracting some 52.4 gigawatts at a cost of £1.2 billion for delivery in 2020-2021.

In the U.K.—as in Spain—IEEFA sees a better way, by which full pass-through to suppliers of the cost of balancing wind and solar could replace the capacity market. Such an approach would punish imbalances more severely and better reward fast-response generation. It could achieve the same outcome as a capacity market, but more cost-effectively, by addressing actual system scarcity rather than theoretical future scarcity.

Granted, there are changes in the pipeline to increase the value of electricity at times of scarcity, arguably making the capacity market less relevant or perhaps even redundant. At present, National Grid’s balancing costs are not passed fully to parties participating in electricity markets. One key reform, to be implemented in November 2018, will double the value that the energy regulator, Ofgem, places on avoiding a blackout.

This and other planned changes will see a corresponding rise in imbalance charges, thus incentivizing suppliers to remain in balance by contracting spare capacity themselves, or by agreeing to contracts with their customers to reduce demand at times of system stress.

Such changes are a step in the right direction.

They raise the question, however, of why Ofgem isn’t introducing more ambitious action sooner. This is a touchy point but very worth exploring, given the ongoing annual disbursement of billions of pounds in capacity payments and the outsize lobbying muscle of utilities to keep such giveaways in place.

Gerard Wynn is an IEEFA energy finance consultant.

RELATED POSTS:

IEEFA Europe: Can Coal Power Hang On?

Europe: ‘Capacity Payments’ Provide a Lifeline to Costly Coal-Fired Generators

IEEFA Europe: Seeds of an Industrial Alternative to Germany’s Regional Lignite Economies