IEEFA Energy Swamp Watch: An Oil-Industry Bailout Is in the Works in Washington

Rex Tillerson, after 10 years at the helm of ExxonMobil, is leaving behind a company with much lower revenues than when he took over, higher long-term debt, lower payouts to shareholders and declining cash reserves.

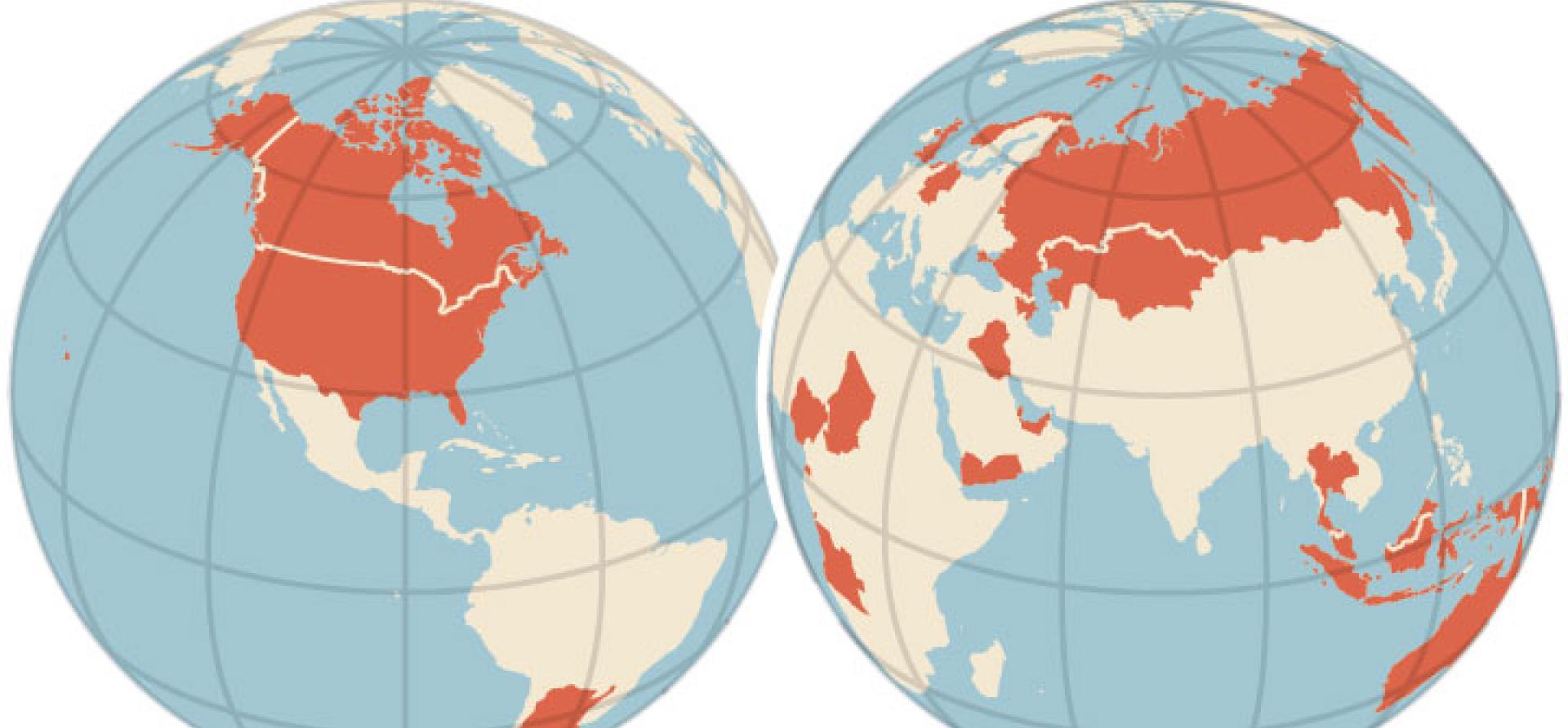

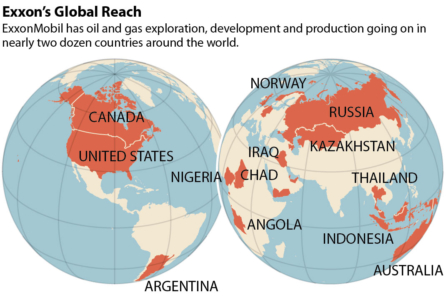

ExxonMobil during Tillerson’s tenure has also had to scale back its oil-reserve numbers as a prolonged oil price decline has rendered its Canadian oil-sands reserves uneconomic. The company, in other words, has become a smaller company under Tillerson (see our October report: “Red Flags on ExxonMobil”), who faces mandatory retirement in 2017.

ExxonMobil during Tillerson’s tenure has also had to scale back its oil-reserve numbers as a prolonged oil price decline has rendered its Canadian oil-sands reserves uneconomic. The company, in other words, has become a smaller company under Tillerson (see our October report: “Red Flags on ExxonMobil”), who faces mandatory retirement in 2017.

That’s why we see little weight in recent characterizations of Tillerson as a model of successful leadership. ExxonMobil is in difficult straits today largely because it has failed under Tillerson’s guidance to adjust to rapidly-evolving energy markets.

He is unqualified to run the U.S. State Department.

What we see in his nomination, in truth, is a de facto oil-industry bailout.

Oil prices hit a low at the beginning of 2016 when they were in the $20-per-barrel range, then rebounded to top $50, which is where they are now. The industry remains cash-starved however.

Margins were under strain even when oil was over $100 per barrel, so producer nations across the board today want a bigger increase. China, to sustain its oil industry, needs the price per barrel to be about $60. The oil-dependent economies of Russia and Iraq are battered by the effects of low oil prices (Russia has tied annual government budgets to $100-per-barrel oil), and they are desperate for a big increase too. Saudi Arabia, wholly reliant on oil, is trying through OPEC to get an increase after two years of industry bloodletting.

Oilmen everywhere want better prices than they’re getting in the current oversupplied market. Tillerson is an oilman.

That fact—combined with the state of oil markets—leaves the incoming administration facing a very important energy-policy moment.

Does it really want to prop up the global oil industry?

Or does it want to address the larger needs of the middle class in developed nations and support economic growth in oil-dependent developing nations?

With Tillerson in charge of foreign policy, Big Oil’s interests would vastly outrank national interests. But he would fail even Big Oil, which is in decline because of energy trends beyond its control, not because of low prices.

He will have failed again, just as he has failed ExxonMobil and its shareholders.

Tom Sanzillo is IEEFA’s director of finance.

RELATED POSTS:

IEEFA Exxon: Why the Abrupt Revision on Reserves?