FirstEnergy Brings Its Bailout Show Back to West Virginia

FirstEnergy is opening a new front in its regional campaign to shift the risks of running uncompetitive coal plants from shareholders to captive ratepayers.

The latest offensive: in West Virginia, where the company revealed on Wednesday that it wants its regulated West Virginia subsidiary, Mon Power, to buy Pleasants Power Station, one of its struggling unregulated coal-fired electricity generators.

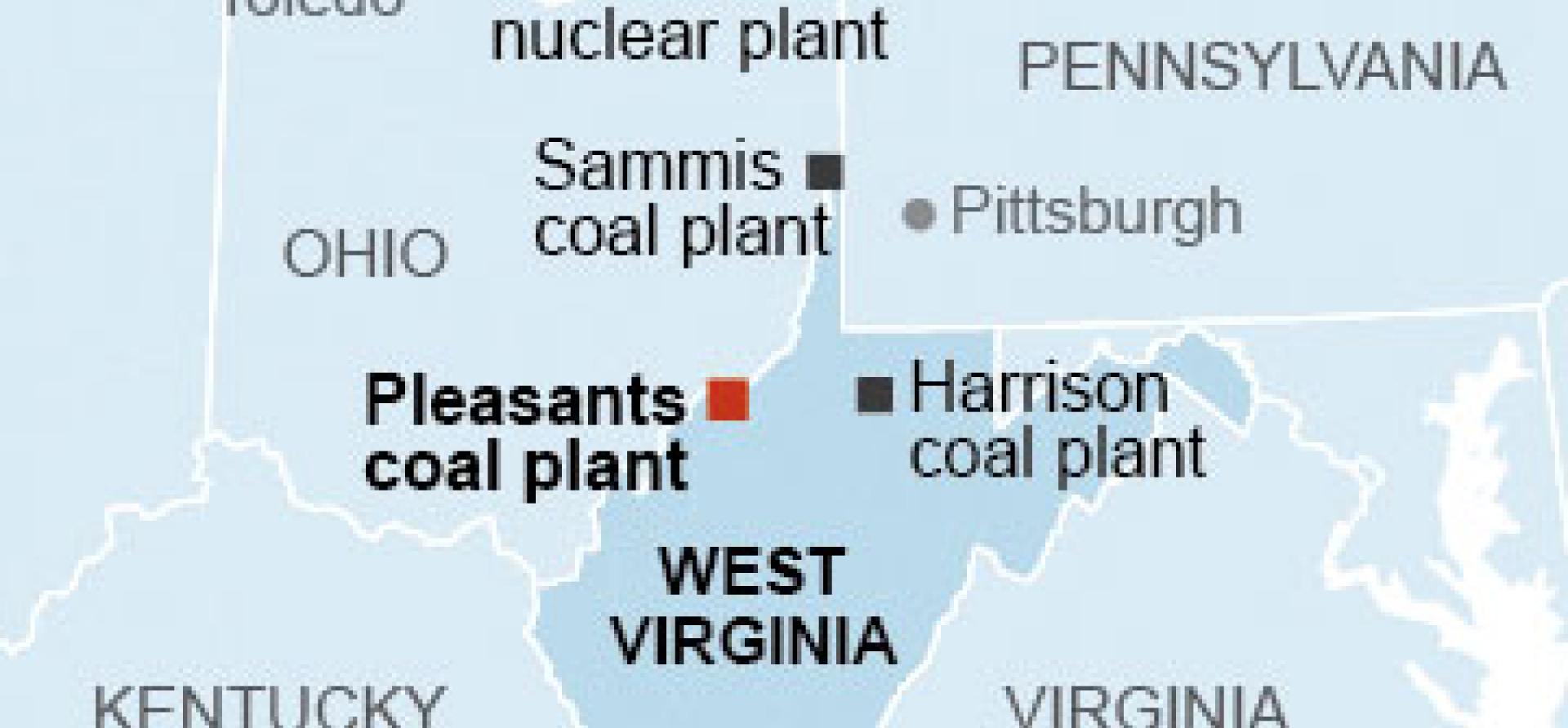

The maneuver would mean a ratepayer-subsidized lifeline for the Pleasants plant, which is on the Ohio River near Belmont.

The maneuver would mean a ratepayer-subsidized lifeline for the Pleasants plant, which is on the Ohio River near Belmont.

FirstEnergy is not new to this game. It began its shift-the-risk-to-ratepayers push three years ago when it transferred the Harrison Power Station near Haywood from one of its deregulated subsidiaries to Mon Power—at an inflated price. FirstEnergy followed up in Ohio by pushing there for state-regulated distribution companies (ratepayers) to pay for the costs of operating its Sammis coal plant, Davis-Besse nuclear plant and its shares of the OVEC coal plants through an eight-year power purchase agreement. And now FirstEnergy is back in West Virginia, proposing Mon Power buy yet another coal-fired plant.

All of these deals are transparent attempts by FirstEnergy to us ratepayer bailouts to save it from its bad business decision a few years ago to invest heavily in unregulated coal plants. That decision left FirstEnergy with a large number of such plants at exactly the time when low energy market prices and stagnating energy demand were making those plants unprofitable.

The current proposals in Ohio and West Virginia are coming under increasing scrutiny. On the same day FirstEnergy unveiled its Pleasants Power Plant scheme on its first quarter earnings call, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission announced that it would be reviewing the Ohio power purchase agreement. That blocks the deal from going into effect even though it has been approved by the Ohio Public Utilities Commission.

And in West Virginia, FirstEnergy is trying to pave the way for its Pleasants maneuver through its integrated resource plan, a long-term planning document filed with the state Public Service Commission that asserts that Mon Power needs to purchase additional capacity and that the most cost-effective option is to purchase an existing coal plant. But there’s a flaw in that approach: Mon Power doesn’t need another coal plant. For most of the year, the company’s coal-fired plants produce more energy than Mon Power customers need, making the company a net seller of energy into the regional electricity market known as PJM.

In fact, there are only a few hours in the year when Mon Power’s peak electricity demand exceeds what Mon Power’s plants produce, and Mon Power fills that gap by purchasing energy from PJM’s energy markets.

So it rings hollow when Mon Power argues that it needs another coal plant.

According to the company, its peak electricity demand in 2020 will exceed generating capacity by 739 megawatts, but 95 percent of the time customer demand will be within its generating capacity. For those 5 percent of hours when demand exceeds the capacity of its existing plants, Mon Power argues that it needs to purchase an 850-megawatt coal plant that will run 67 percent of the time. If the Pleasants Power Station deal goes through, Mon Power will be generating surplus energy for decades to come.

While Mon Power argues that customers will benefit because the excess energy will be sold into PJM and the revenues credited back to ratepayers, all that tactic does is effectively make captive ratepayers into speculators in PJM’s energy market. That play hasn’t worked out very well so far. With energy market prices low, revenues from Mon Power’s sales of its existing surplus energy into PJM have declined, leading to a recent rate hike for Mon Power customers to cover the gap. Forcing ratepayers to shoulder the burden of even more excess energy makes no sense.

Finally, it appears that FirstEnergy’s already-feeble justification of the need for this coal plant has been overstated. In comments filed at the West Virginia Public Service Commission this week, lawyers from Earthjustice noted that Mon Power overstated its capacity shortfall by several hundred megawatts. Instead of facing a 749-megawatt capacity shortfall by 2020 (and supposedly growing to 850 megawatts by 2027), Mon Power is likely facing a substantially smaller shortfall. This makes it all the more reasonable to assume that such a shortfall could be met through a combination of energy efficiency, demand response and renewable resources—all resources ignored by FirstEnergy in its integrated resource plan.

Cathy Kunkel is a West Virginia-based IEEFA energy analyst.