Investment Bank Blindness to Risk in Fossil-Fuel Sector

When did the finance industry abandon basic long-term business and investment principles?

And why does an environmental organization have to play the role of canary in the coal mine?

A new report by Rainforest Action Network shows just how deep the banking sector is buried in fossil fuel investments with shrinking returns. The RAN research is striking because it shows that investment banks appear to have abandoned any concern for even short-term returns, much less long-horizon results. Remarkably and inexplicably, these investors have chosen to maintain their robust ties to coal, oil and gas, sectors dripping all with red ink and trapped in a steady, downward spiral.

As a former government official with responsibility for a very large pension fund, I have been alarmed to see the financial collapse of coal and the erosion of profitability in the oil and gas sectors without seeing mainstream institutional investors raise red flags.

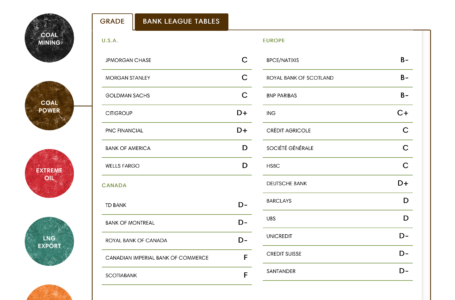

Coal markets have crumbled, and today’s oil markets are severely troubled. The numbers don’t lie: Most of the major coal companies in the U.S. have lost 100 percent of their value and over 50 coal companies have declared bankruptcy. Although most of the relevant research from large investment banks has in fact sounded the alarm on coal, the same banks that produce this research continue to service the coal industry. RAN reports $42 billion of investment bank activity in coal mining and $24 billion in coal-powered generation between 2013 and 2015. The leaders in this questionable commitment are Citigroup and Deutsche Bank.

The oil industry isn’t doing much better than coal. It has seen 77 bankruptcies since the start of 2015, and both small and large oil companies have cancelled billions of dollars worth of oil-sands projects in Canada. Around the world, oil and gas capital expenditure budgets are being slashed due to weak markets that characterized by low prices. Yet RAN has identified $308 billion in bank investments in high cost oil production from 2013 through 2015.

The RAN report highlights dubious bank support for a proposed coal plant in Rampal, Bangladesh, for example. Many other instances of institutional investors making bad bets included one involving bank support for a scheme by the Obama administration and the World Bank to build a costly new coal plant in Kosovo, contrary both to U.S. government and World Bank climate policy and in the face of financial warning signals indicating that such projects are badly out of stop with modern energy markets.

Investment banks to some extent have been able to shrug off coal-investment losses, since coal was not much of a customer for their services to begin with, given its small size, its history of marginal returns and it sub-investment-grade credit ratings. But shrugging off much larger losses in oil and natural gas will be more difficult.

Ironically, bankers seem more interested in moving forward with oil and gas deals—because the deals generate fees for them—than do the oil and gas companies themselves. Oil companies, in particular, are terminating projects based on what they see coming down the pike. What the oil companies know, and what the banks seem to be missing, is that the former long-term cornerstones of growth—oil sands, natural gas and conventional oil—face a future of limited profitability. The issue transcends climate-change debate per see, and part of the folly of banks is captured in this passage from the RAN report:

“The continued financing of fossil fuels is also becoming a risky strategy for banks, even on purely self-interested grounds. With a grassroots global climate movement gaining strength daily, the unprecedented pressure on global political leaders to act on climate and transition away from fossil fuel-based energy will only grow in strength and urgency in the coming years.”

Long-term capital expenditure decisions in fossil fuels require an outlook that sees past the daily fluctuations of commodity trading to the bigger picture of industry profitability. Oil prices were down to $28 per barrel earlier this year, and the current much discussed “market recovery” is placing prices somewhere in the $50-dollar-per-barrel range. That’s not much of a recovery because $50 oil is far below break-even pricing for oil sands and other expensive forms of development.

Overleverage in the natural gas industry is also being checked now by a host of bankruptcies, a trend that reflects recognition of a low price outlook for natural gas. Investments based on short-term price fluctuations will only add volatility to oil and gas markets, something that was once—and still should be—anathema to sound banking practices.

Any up-cycle in fossil fuels is not likely to be as long or to push prices as high as previous cycles did, meaning that less capital will be available to weather the next financial storm. Bankers who fail to heed the market warnings are likely to end up with far worse than bad grades from the Rainforest Action Network. They will probably end up sporting severely diminished balance sheets (and dunce caps) as they are outcompeted by investment alternatives to fossil fuels.

Tom Sanzillo is IEEFA’s director of finance.

RELATED POSTS:

15.5% Drop in China Coal Production Shows Transition Gaining Speed

IEEFA Data Bite: Renewables, in U.S. Government’s Latest Snapshot, Are Closing In on Coal