China’s offshore wind industry giant stimulates global growth

Mingyang’s well-funded overseas expansion could benefit the global supply of offshore wind power

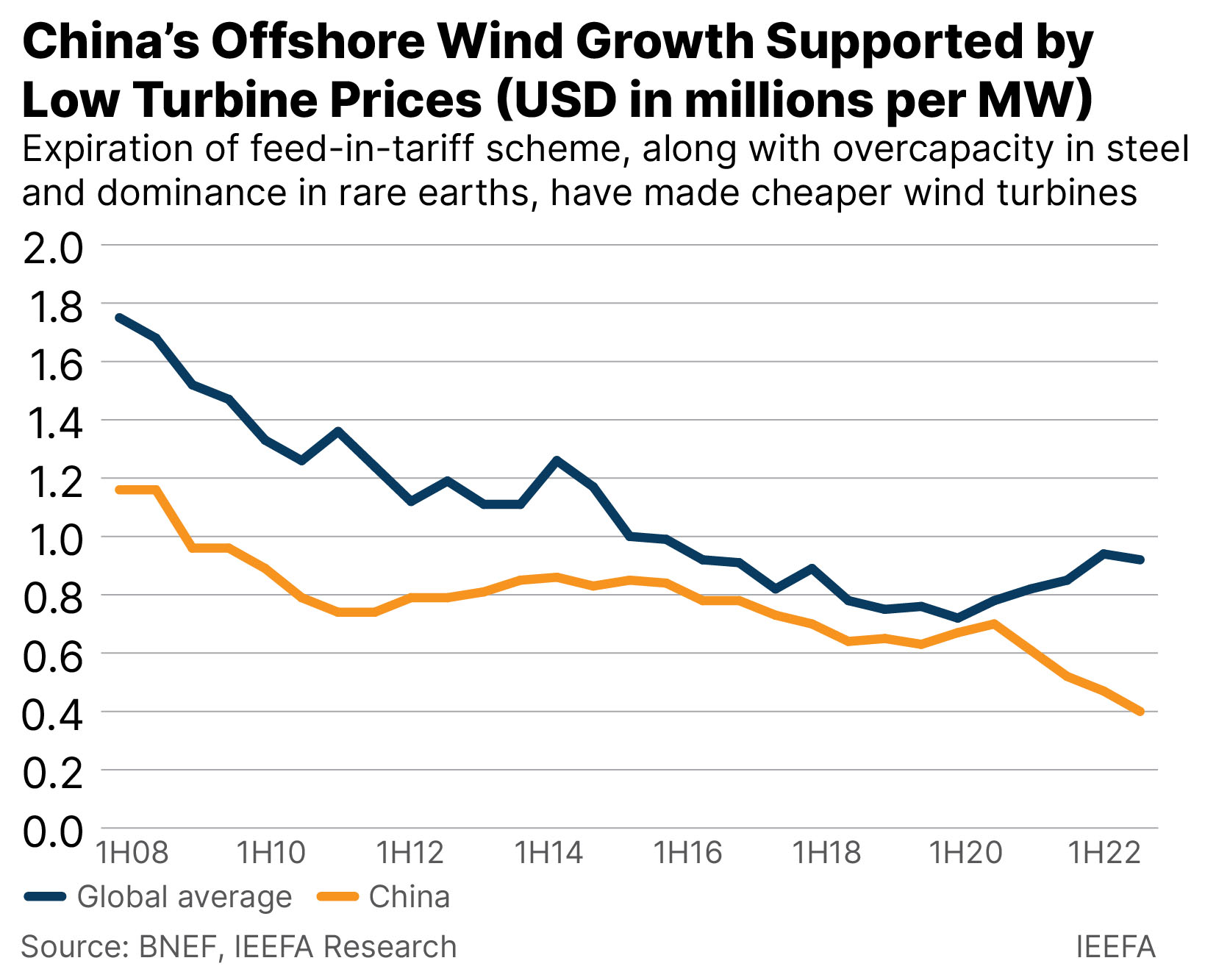

5 September (IEEFA Asia): In 2019, China announced that the feed-in-tariff scheme for offshore wind would end in 2021 and move to an auction. This policy change led to China’s 2021 addition of nearly 17 gigawatts (GW) on its own, more than the world had ever added globally in any single year.

China is currently home to the world’s largest offshore wind industry. From 2010 to 2020, the country’s offshore wind capacity growth accounted for 32% of total global expansion. Between 2020 and 2022, one out of every five turbines installed offshore is a model by Mingyang, China’s largest private wind turbine manufacturer.

A new report by IEEFA’s Energy Finance Analyst Norman Waite analyses the rapid growth of Mingyang and China.

“Mingyang’s overseas expansion could drive turbine sizes higher, wind farm development prices lower, and benefit the supply of offshore wind power in many markets around the world,” says Waite.

Cost competitiveness

Chinese turbine prices have dropped as preferential feed-in-tariff schemes expired — onshore in 2020, and offshore in 2021.

In fact, China now offers the cheapest wind turbines in the world. China’s overcapacity in steel, dominance in rare earths and competitive supply chain combine to keep gross profit margins 14 percentage points higher than international turbine players on average.

In comparison, non-Chinese turbine suppliers continue to lose money, observes Waite.

“If companies need equipment from Chinese suppliers, they face shipping bottlenecks holding freight rates three times higher than 2019,” says Waite.

This is in addition to globally higher rare earths’ prices, seen in the Shanghai price for Neodymium, which is two and a half to three times higher than pre-COVID levels.

“Non-Chinese turbine manufacturers looking for the neodymium, dysprosium and terbium – found in the strong permanent magnets necessary for wind turbines – are likely to face an even more concentrated and even more politically fraught supply structure, which seem unlikely to resolve quickly,” says Waite.

National market growth

China’s ample steel production, policy clarity, and homegrown supply chain have created a diverse market of large-scale offshore wind turbine choices.

“At present, we estimate that China has 11 turbine manufacturers, offering four types of generator technologies, with a total market of 44 models above 7 megawatts (MW),” says Waite.

Waite adds that China’s solar industry grew from European demand, its wind industry grew out of domestic demand, raw materials advantages and an import substitution effort by the government.

Geographically speaking, there are strong winds offshore, both nearby along its coast and farther out in deeper waters within China. Since 2020, seven out of ten offshore turbines have been installed in China.

“China is now the world’s largest country for solar (as of 2015), onshore wind (2011), and offshore wind (2021) energy generation equipment demand,” says Waite.

IEEFA research finds 38 offshore wind farms in China that employ multiple turbine models, frequently from more than one supplier.

“This practice of mixed model farms appears rare outside China,” says Waite. “China’s mixed model farms can accelerate learning as wind turbine technologies and designs can be compared in real time.”

Turbine engineering and new market success

The levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) is the average net present cost of electricity generation for a generator over its lifetime. In China, offshore wind now has an LCOE that is near coal (USD78MWh including transmission vs. USD76MWh).

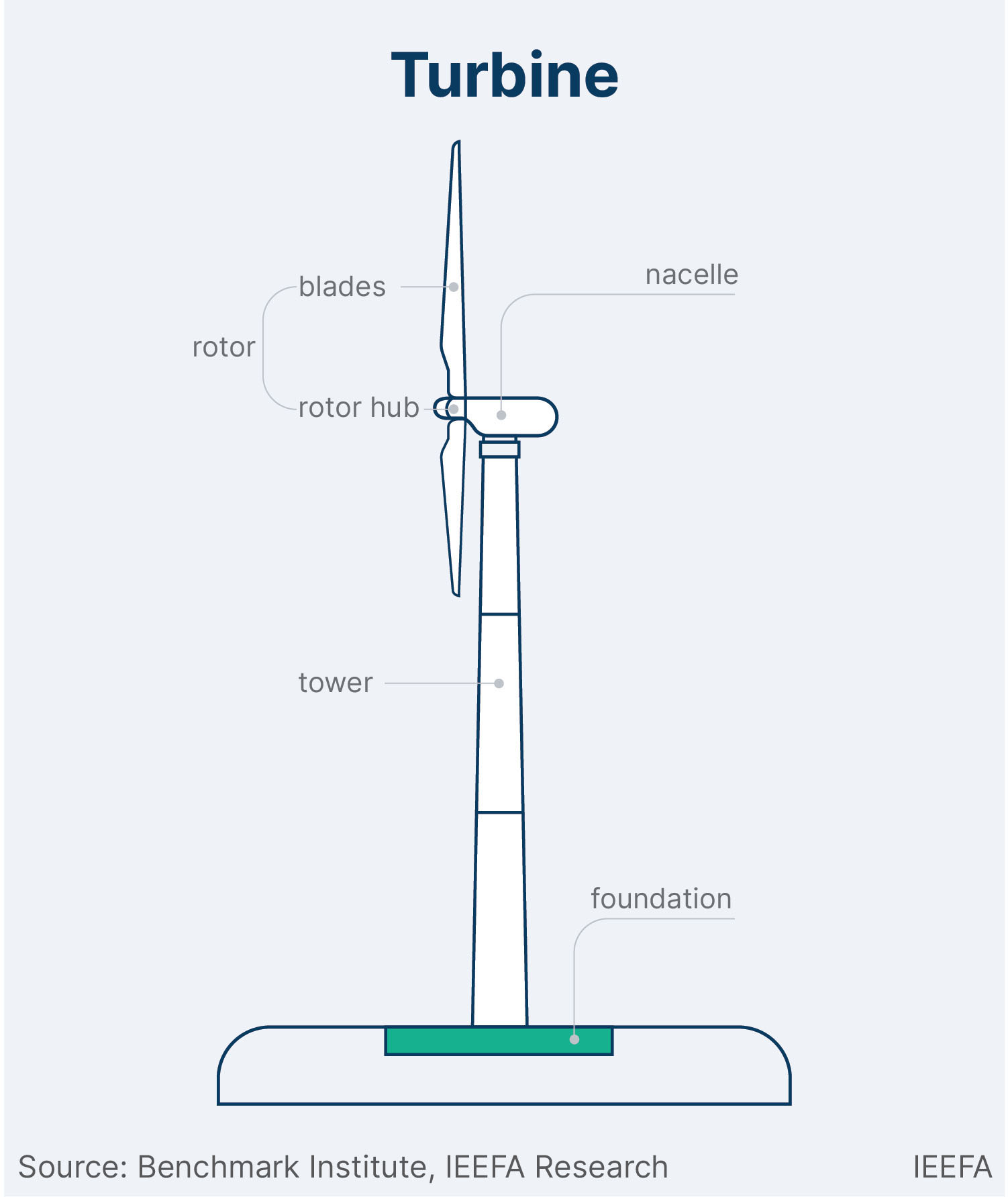

Offshore projects generally cost more because of construction and maintenance challenges that can raise the cost of capital for a project. The solution has been to build larger turbine sizes that reduce the number of turbines, as LCOE becomes lower for larger units of offshore turbines.

“Mingyang has consistently led the way toward larger offshore units in China and appears like it will continue to do so,” says Waite. “It was the first to introduce 6.5MW, 8MW, and 11MW offshore wind turbines to the local market.”

In the quest for bigger offshore turbines, Mingyang has become one of the first to gravitate toward a type of permanent magnet synchronous generator, known as medium speed hybrid gearbox (MSPMSG). To date, Mingyang has already become the world’s largest supplier of hybrid MSPMSG turbines and supplied almost 90% of hybrid drives in China last year.

In contrast to other Chinese turbine players, Mingyang has moved much of its production in-house. The company keeps external suppliers for redundancy, but does much of its production of blades, drive gearboxes, and other systems on its own to protect its intellectual property.

While the German manufacturing firm Aerodyn had partnered with many other suppliers in the mid-2000s, Mingyang had the first mover advantage to go beyond licensing Aerodyn designs to initiate joint development of new models.

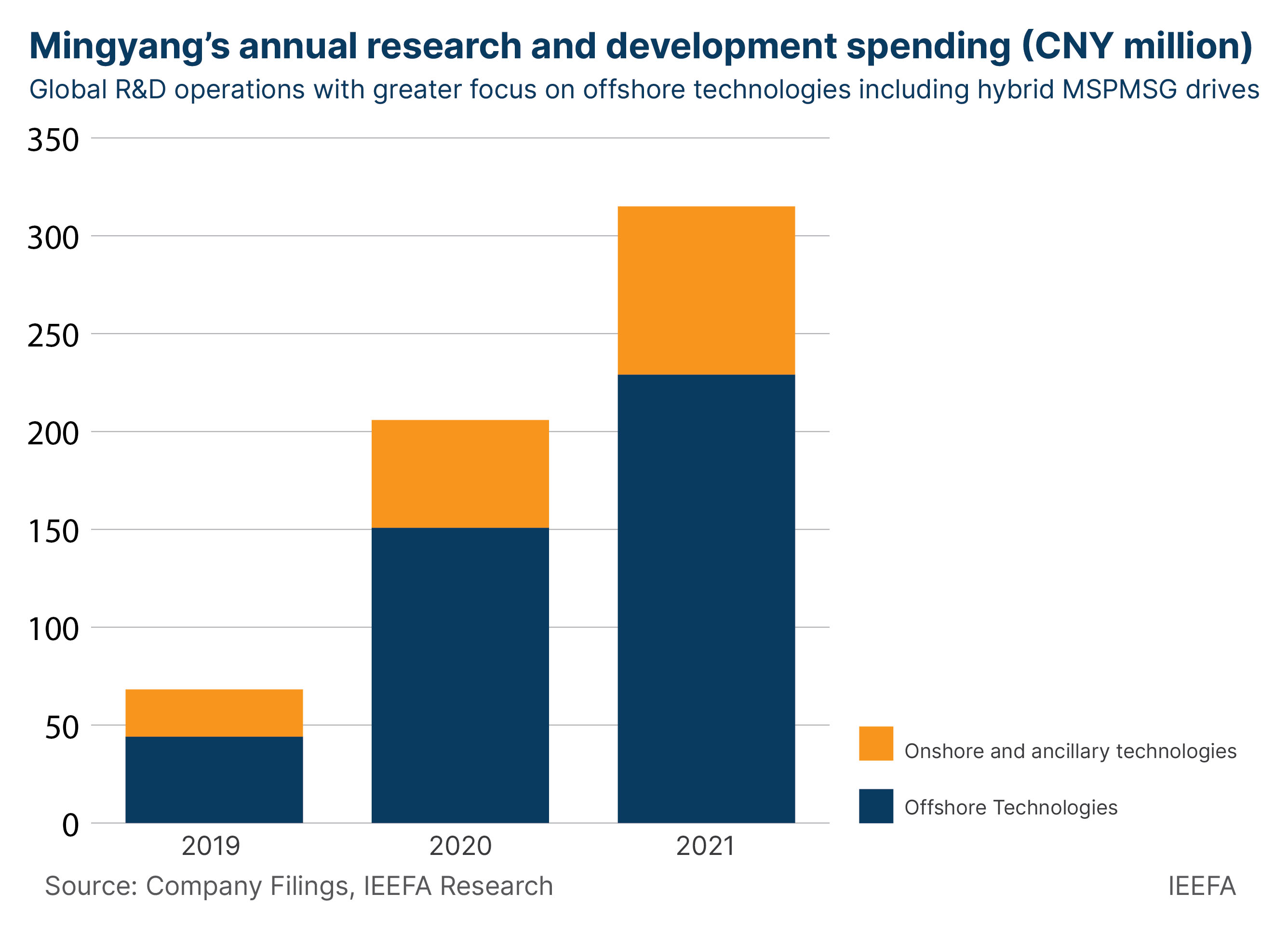

IEEFA estimates that 50-55% of Mingyang’s revenue is still sourced from onshore turbine models. However, this ratio may decline as the company’s research and development remain squarely aimed at offshore technologies.

In the report, Waite also analysed the East Asian markets of Japan, Korea, Vietnam and Taiwan, which are all mired in a degree of uncertainty for Mingyang’s expansion.

“In comparison, the UK is a mature and transparent market with more capacity growth potential by 2030 than all four of those East Asian markets put together. Mingyang’s UK investment opportunity could be a game-changer for the company and the industry.”

Read the report: Chinese Offshore Wind Goes Global

Report contact:

Norman Waite ([email protected])

Media contact:

Alex Yu ([email protected]) Ph: +852 9614 1051