Arch Coal, the Second-Biggest U.S. Producer, Is in Trouble

Arch Coal has posted significant losses for three years running now and as 2015 unfolds it appears its performance will remain in the red.

Arch Coal has posted significant losses for three years running now and as 2015 unfolds it appears its performance will remain in the red.

Last week the company announced it had lost $553 million in 2014, which is an improvement over 2013, when the company lost $736 million, but not very promising. A deeper look, beyond just the loss column, reveals a company in distress.

Arch executives say they expect coal markets this year to perform about the same as they did last year, which was a brutal 12 months for U.S. coal producers. This admission—that 2015 will bring no upturn— suggests that whatever initiatives Arch pursues this year will be geared solely at reducing losses. The company is in hunker-down-and-survive mode.

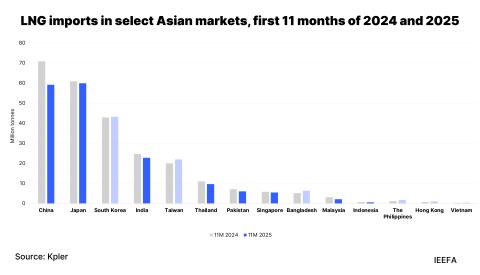

Arch’s situation has an industry-wide familiarity. Declining prices for coal both in the U.S. and internationally have frustrated all efforts by U.S. producers to improve revenues. Historically unprecedented pressure at home from natural gas and renewable energy and abroad from Indonesian, Australian, Colombian, South African and Russian coal suppliers combined with new policy and coal-market direction in China and India are forming the perfect storm.

Arch CEO John W. Eaves has conceded dormancy in near-term opportunities, expressing a sunny belief instead in future markets. This optimism was expressed on the very same day that Wood Mackenzie, a key industry consultant and previously one of the most bullish firms on coal exports, signaled its downgrade of international coal markets. WoodMac joins Bernstein Research, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, UBS, Citigroup and a host of others who have lost faith.

Arch is burning money. It is spending millions of dollar per year to stay the course in its proposal to develop its Otter Creek, Mont., export mine despite diminished market expectations. It will shell out $50 million this year to make yet another payment on its federal lease for coal reserves that underpin the South Hilight project, another Montana property Arch wants to turn into an export spigot. In 2015, it will incur $50 million in contract costs incurred in part by weak export markets.

The company’s hope of having investors and taxpayers build a Seattle-area coal-export port for its U.S. mines remains elusive. The State of Washington should wonder whether Arch will be the ultimate operator of the port or if they are just granting future rights to an unknown owner. Others who must partner with the company must be wondering how serious its expansion plans are when Arch’s Black Thunder mine in Wyoming produces barely 100 millions tons of coal annually (it has the capacity to yield 130 million tons). The company’s long-term razor-thin margins in the Powder River Basin of Montana and Wyoming should also be a cause for skepticism.

Arch executives say they see its problem as a cyclical phenomenon that it can afford to wait out, so its strategy is a purely cost-reduction one: cutting capital expenditures, eliminating investor dividends, reducing pension contributions and tightening production. This has helped the balance sheet in the short run. In the long run, it’s a road to nowhere.

Company executives say also they’re comfortable with Arch’s liquidity position, stating that it has $1.2 billion in cash, short-term investments and borrowing facilities and that this will pay the bills until markets turn around. Will it?

Arch said this time last year that it had $1.4 billion in liquidity, so by its own accounting, it has seen significant erosion in liquidity. And the definition of “liquidity” today can be dubious. It’s a wonder of corporate finance that short term-credit lines are now counted as liquidity (credit lines create debt, which of course much be paid back). It’s also a wonder of corporate finance that short-term investments, traded on the market and subject to discounts, diminution and other deductions by bankers and other intermediaries are treated the same as balance-sheet cash.

Arch’s year-end disclosure of cash and cash equivalents is $774 million, which is down substantially from $911 million this time last year. If you add up missed pension payments, missed dividends and the like, you might wonder how liquid the company actually is.

Cash on hand will become increasingly and more painfully relevant in the next few months. In June, Arch must show $550 million in liquidity to comply with its debt covenants. If, for argument’s sake, the company were to do a little better in 2015 than last year, and lose, say, only $450 million instead of $514 million, by June it could be very close to that $550 million test. One or two bad weeks would be the final straw in the company’s fast-deteriorating revenue position.

These short-term problems are only worsened by the $600 million in market capital losses as Arch stock has tanked, sending the company’s debt-to-equity ratio to troubling levels. With $5.1 billion in outstanding debt due beginning in 2018, investors are surely doubting the company’s future.