IEEFA: After a terrible 2020, the oil industry’s story has turned political

It was a dismal year for oil and gas. As the pandemic sucked the wind from the sails of the global economy, oil demand slumped, stockpiles swelled, prices sagged, capital spending collapsed, debt ballooned, profits evaporated, and bankruptcies skyrocketed. After this torrent of bad news, the energy sector ended the year in last place in the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index.

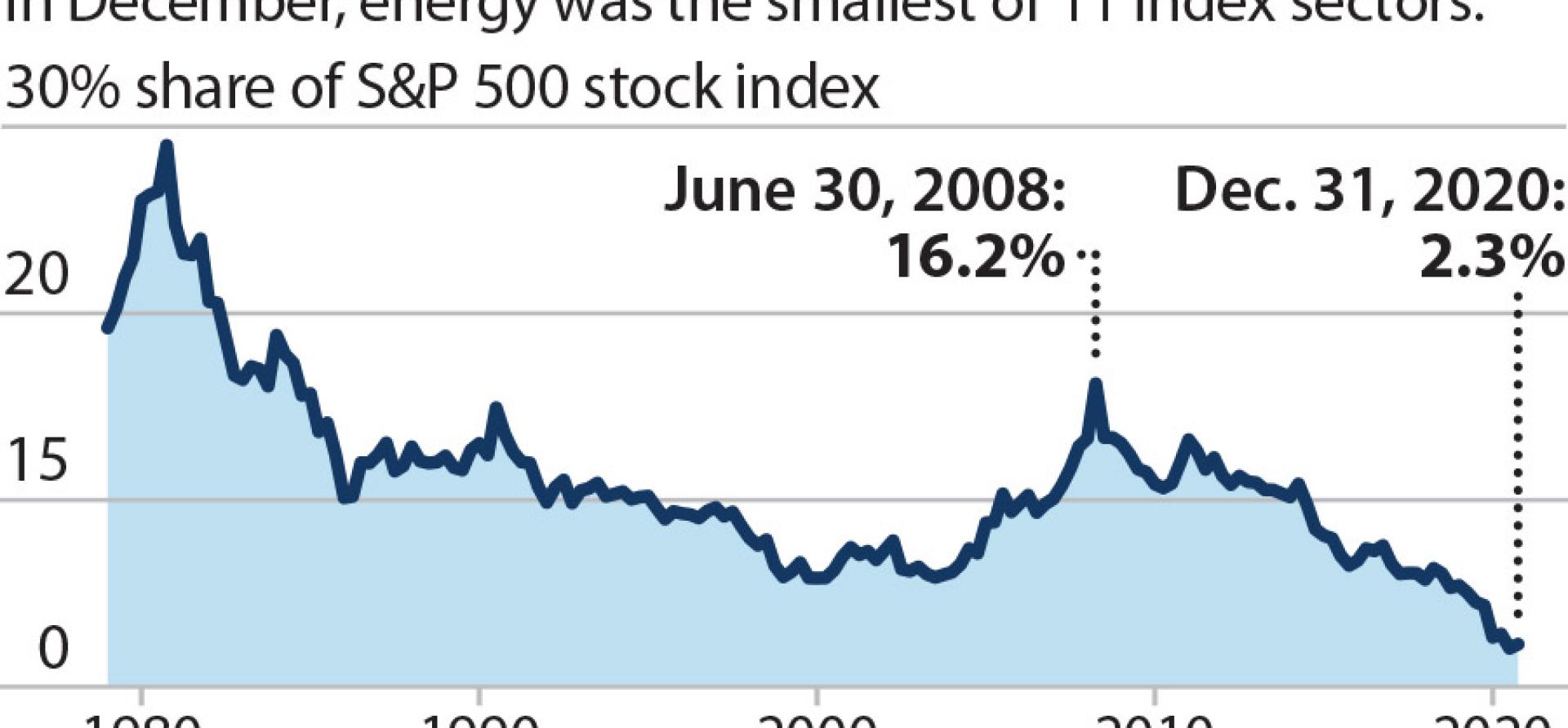

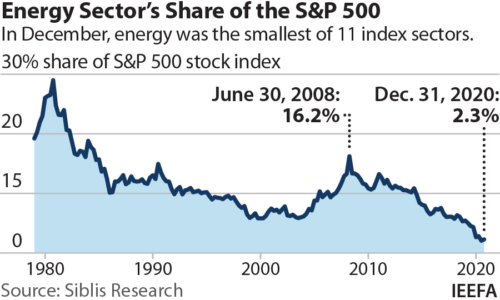

Last place is now familiar territory for oil and gas. The industry placed at the bottom of the S&P 500 in five of the last seven years, and second-to-last in a sixth. Even so, 2020 marked a new low. Within the S&P 500, the energy sector lost more than a third of its value during the year, even as the index as a whole rose by 18 percent. (The next-worst sector, real estate, lost just 2 percent.) By the end of the year, energy made up slightly more than 2 percent of the S&P 500’s value—down from 16 percent just over a decade ago, and almost 30 percent a few decades before that. Oil fell so far that ExxonMobil, once the world’s largest private company, was booted out of the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

Last place is now familiar territory for oil and gas. The industry placed at the bottom of the S&P 500 in five of the last seven years, and second-to-last in a sixth. Even so, 2020 marked a new low. Within the S&P 500, the energy sector lost more than a third of its value during the year, even as the index as a whole rose by 18 percent. (The next-worst sector, real estate, lost just 2 percent.) By the end of the year, energy made up slightly more than 2 percent of the S&P 500’s value—down from 16 percent just over a decade ago, and almost 30 percent a few decades before that. Oil fell so far that ExxonMobil, once the world’s largest private company, was booted out of the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

Yet there’s already talk of an oil and gas “rebound” in 2021. Yes, that could happen. Demand will likely pick up as COVID restrictions ease. Prices could rise. Companies that skimp on capital spending may finally generate enough cash to chip away at their debt. At a minimum, the sector should improve upon last year’s abysmal showing—and for a perennial underachiever, even mediocrity would be an improvement.

Still, the stories we’ll be watching in 2021 will transcend the question of an oil rebound, with its myopic obsessions with prices, production volumes, and quarterly profits. Instead, we believe that the real fight over the oil and gas industry’s future has shifted to a different arena: Politics.

The oil industry faces political conflicts at every conceivable level

Politics writ large, that is. In its shrunken and financially stressed state, the global oil industry now faces political conflicts at every conceivable level, from the lofty stages of international diplomacy, to the halls of Congress, to the corridors of federal agencies, to corporate boardrooms, statehouses, and the conference rooms of trade associations. Politics could even spill into the streets, in front of the banks that provide the capital that is the lifeblood for the cash-starved industry. These battles will pit portions of the industry against one another, sapping the sector’s vitality and furthering muddying its prospects.

Here’s just a taste of the political battles poised to embroil the industry this year:

- Corporate governance. We expect to see more board infighting over strategy and personnel. It’s already here: D.E. Shaw, one of the world’s biggest hedge funds, recently joined with activist investors in challenging ExxonMobil’s board over excessive spending and weak strategy, while JPMorgan Chase, the top fossil fuel financer in the U.S., ousted board member and former ExxonMobil CEO Lee Raymond after a successful campaign by outside investors. These are merely the tip of the iceberg.

- U.S. politics. Oil lobbyists are gearing up to beg for another “Main Street” bailout, even as they work behind the scenes to thwart investments in renewables and efficiency. Meanwhile, a battle over federal fracking rules could pit the industry against itself, with some firms fighting to maintain access to public lands and others looking for the pause button, with both sides hoping to see their competitors wither.

- OPEC+. Expect high-stakes dramas over quotas and price targets, as the globe’s low-cost producers jockey over market share and profits against a backdrop of low prices and fiscal instability. Saudi Arabia could continue to lock horns with Russia, Iran, and Qatar—as the U.S. oil sector watches from the sidelines, desperately hoping that the OPEC coalition reigns in production to keep prices high.

- Industry competition. In the U.S., we’ve already seen deep rifts between big and small producers over production limits and methane emissions. We may see similar conflicts between supermajors and independents; national oil companies from different nations; stockholders vs. bondholders; and oil vs. gas. The interests of different segments of the oil industry no longer align—and financial stress brings conflicts to the fore.

- Institutional investors: Last December, the New York State pension fund launched a new divestment standard, creating a blueprint for fossil-free portfolios. Questions about the fiduciary responsibility of divestment have now been answered not only by oil’s dismal stock market performance, but also by Norway, New York State and New York City, as well as BlackRock. All increasingly view fossil fuels as wealth hazards.

- Climate. Global climate and indigenous rights campaigners are notching real successes in challenging wasteful fossil fuel investments. France, for example, just dealt a blow to a U.S. liquefied natural gas project, canceling a supply contract over climate concerns.

The list goes on. In oil-producing states, shrinking oil and gas revenues will fray state budgets, while blue states are filing lawsuits to collect damages from fossil fuel companies. Venezuela’s political crisis could lead to further declines in exports, or alternatively, a revival. Even oil and gas trade associations could face renewed internal strife.

Although the oil industry is no stranger to power games, the industry once viewed politics as just another risk to be managed, or another advantage to be exploited. Global supermajors, smaller independent companies, and trade associations all sang from the same hymnal, preaching a gospel of loose regulation and low taxes.

This unity came easily because the industry’s finances seemed secure. Global demand was rising and reserves appeared scarce, so strong prices and robust profits looked assured, no matter who won the political games. In that era, technology, geology, and global demand growth occupied the main stage. Politics was mostly a sideshow.

In this new era, demand is growing slowly, if at all

But starting in about 2014, a collapse in oil prices eroded the industry’s economic foundations. In the new era, demand is growing slowly, if at all. Reserves are cheap and abundant. Oil and gas now face rising competition from low-cost renewables, electric vehicles, and plastics recycling. Meanwhile, a sophisticated and determined global climate movement grows ever stronger.

In this new reality, the former sources of value have become vehicles for destroying value. Production has become overproduction. Reserve replacement has become an unnecessary cost. The 2020 tsunami of oil bankruptcies and write-offs represent a belated reckoning with the overleveraged, free-spending ways of the previous era.

Late last year, oil guru Daniel Yergin argued that oil’s future will be dominated by the United States, Russia and Saudi Arabia, with politics setting the stage for a competition among energy choices, following scripts drawn from a mixed set of political ideologies. All of the players would fight for the largest possible piece of the fossil fuel pie.

But the smart money is now betting that the pie will keep on shrinking. That will leave lower rewards for everyone, even the victors of the political infighting. Moving forward, as long as demand for oil and gas remains weak, markets remain oversupplied, renewables get cheaper, and the climate opposition stays firm, investors will have no choice but to look elsewhere for both growth and value.

Clark Williams-Derry ([email protected]) is an IEEFA energy finance analyst.

Tom Sanzillo ([email protected]) is IEEFA’s director of financial analysis.

Related items:

IEEFA update: ExxonMobil’s financials indicate slide under CEO Darren Woods’s leadership

IEEFA: From zero to fifty, global financial corporations get cracking on major oil/gas lending exits