A Test Now for the Western Balkans: Adhere to the Past or Embrace a New Energy Economy?

Emerging still from the civil wars that followed the collapse of Yugoslavia a generation ago, the six countries of the Western Balkans today face an unprecedented energy-policy moment.

The essential question facing Albania, Bosnia, Kosovo, Macedonia and Montenegro, and Serbia: Whether to adhere to a costly coal-fired electricity-generation past or embrace the new global energy economy.

Opportunity knocks by way of reforms that include the wider introduction of competitive electricity markets and greater trans-border renewable-power interconnections. The framework for progress—and the stepping-stone to membership in the European Union—is in place already in the 2005 Energy Community Treaty. That pact, if properly enforced, could prove a modern-day equivalent of the 1951 European Coal and Steel Community, which founded a common market between France and Germany and led to the creation of the EU.

Indeed, the Energy Community Treaty is already driving greater electricity-market integration, regional cooperation, interdependence, and trade—all in service of a pan-European “energy union” that aims to deliver security of supply, lower costs and fewer carbon emissions.

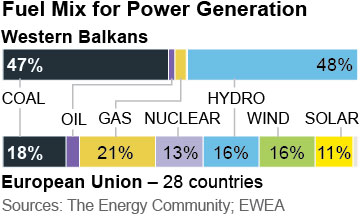

Coal-fired generation is on the wane across the EU, and the nations of the Western Balkans are in a position to follow that trend.

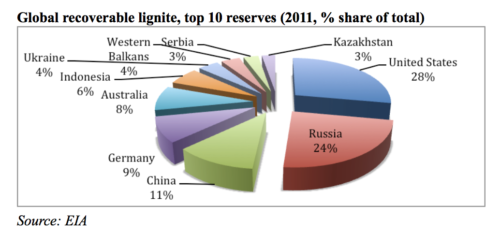

Yet regional leaders seem hobbled by a lingering attachment to big lignite reserves in Serbia, Bosnia and Kosovo, a region that ranks eighth globally in such reserves. Complicating the issue is the reality that the region’s Soviet-era power plants need replacing, a fact that is driving a tilt toward new projects and that is being used as an opening by national elites who have entrenched interests in developing coal assets.

Powerful outside forces are also on the wrong side of history on this point, as the World Bank, for example, offers support for the construction of a new national coal plant in Kosovo in violation of its own policies and oppositions to new coal plants.

THE GOOD NEWS IS THAT THE ENERGY COMMUNITY TREATY IS PULLING GRADUALLY IN THE OPPOSITE DIRECTION, creating integrated, liberalized energy markets and supporting standards on energy, the environment, renewables and electricity-sector competition.

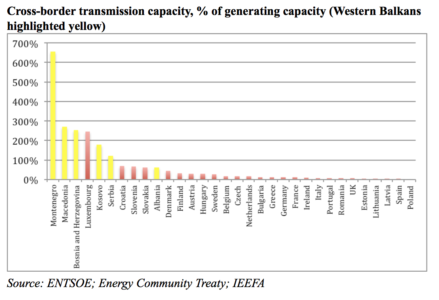

In electricity markets, Western Balkans nations have not just the legal framework but the hard infrastructure in place. They have cross-border transmission assets that exceed most existing EU member states: while the EU has targeted interconnector capacity at a minimum of 10 percent of national power generation assets, the Western Balkan collectively has nearly 200 percent.

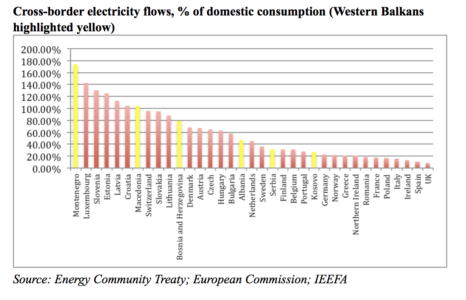

What the region lacks is the soft infrastructure—liberalized power markets that encourage competition and cross-border regimes that can match power demand with grid capacity. By directing electricity to flow from less expensive to more expensive markets, such coupling would cut average power prices, saving consumers money. Instead, the region’s electricity supply remains highly regulated, protecting the status quo and lacking transparency. The situation perpetuates corruption, and the end result is poor use of existing assets as cross-border electricity flows fail to capitalize on available capacity.

Full enforcement of the Energy Community agreement would wrest control of competitive electricity markets from the grip of existing state-owned enterprises and would link national markets, much as the EU has done across Europe.

The benefits of Western Balkans reform are clear:

- First, greater transparency will deprive corrupt middlemen of the persistent opportunity to cream off sales between murky state-owned generators and suppliers.

- Second, as markets are linked, consumers will see lower wholesale power prices (the European Commission estimates that market coupling saves electricity EU consumers some 2.4 to 4 billion euros annually).

- Third, better integration will allow more efficient use of existing grid and power generation that, combined with market integration, will favor the development of clean renewables by creating a wider network to reduce the intermittency effects of wind and solar power. This benefit has special resonance in a region where electricity generation is so concentrated: in Albania, 95 percent of generating capacity comes from hydropower; in Kosovo, 98 percent comes from coal. The average for non-hydro renewables across the region is less than 0.5 percent.

The nations of the Western Balkans are at an electricity-generation crossroads. Will they cling to the past or step into the future?

Gerard Wynn is IEEFA’s energy-finance consultant, Europe.

The Western Balkans region contains significant lignite reserves, a fact that helps explain its lingering attachment to coal.

… as are cross-border electricity flows, trends that indicate the strong potential for further modernization.