Resource firms show transition in exploration and capex spending

Key Findings

The Australian government’s call for renewed oil and gas exploration to enable increased output runs counter to a decade-long trend of declining spending on gas exploration.

Gas exploration has been overtaken by spending in metals exploration and production capacity, at a time when global investment in renewable energy has exceeded investment in new fossil fuel capacity.

The industry’s limited spending on exploration undermines its claims that Australia needs more gas, while a looming global LNG supply glut may further deter future gas exploration and development.

Australia is a significant producer of metals used in renewable energy infrastructure, and government policies should prioritise exploration spending for these critical minerals, rather than oil and gas.

This analysis is for information and educational purposes only and is not intended to be read as investment advice. Please click here to read IEEFA Australia’s full disclaimer.

In its Future Gas Strategy, the Australian government underlines the importance of exploration to enable new sources of gas supply.

It sees increased output as a way to address the energy challenges of the coming decade, following 10 years of declining spending on oil and gas exploration. The decline in petroleum exploration has come at a time when the world is awash with gas, and the global energy sector is investing almost twice as much in clean energy as it does in fossil fuels.

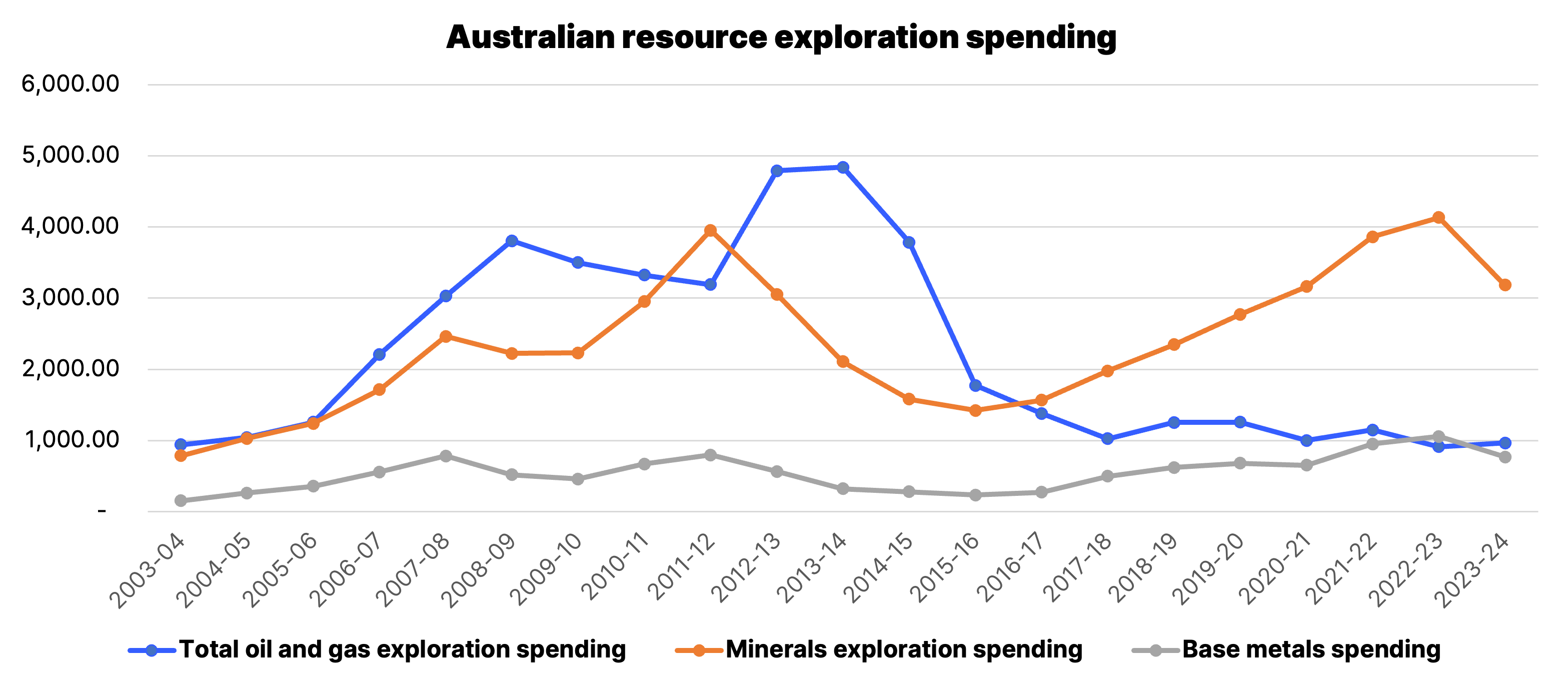

The investment transition to a more sustainable energy system has also been reflected in exploration spending by extractive industries. Minerals exploration spending has exceeded oil and gas exploration expenditure for the past seven years, while capital expenditure (capex) on minerals projects has exceeded oil and gas capex since 2018-19.

Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) shows that petroleum exploration across Australia dropped to a 21-year low of AU$912.90 million (US$602 million) seasonally adjusted in the 2022-23 fiscal year to 30 June. It was the lowest expenditure on the search for new gas and oil prospects since the AU$879.60 million spent in 2001-02, and down 81% from the record AU$4.84 billion spent in 2013-14 – when Australia was in the midst of its largest-ever liquified natural gas (LNG) expansion.

Petroleum exploration spending has rebounded in the first nine months of 2023-24, totalling AU$964.50 million. If spending levels are maintained in the April-June quarter, total spending will reach the levels seen in 2019-20 of around AU$1.25 billion. Nonetheless, this expenditure remains dwarfed by the spending on minerals exploration.

The money moves into minerals and metals

For companies mining metals that are pivotal to the energy transition, exploration budgets are on the rise. Exploration spending on copper, nickel, cobalt, lithium and other critical minerals have exceeded petroleum expenditure for the past four years based on ABS data. This in turn has contributed to the record exploration of AU$4.13 billion in the 2022-23 fiscal year.

Figure 1: Australian resource spending, AU$m

Source: ABS.

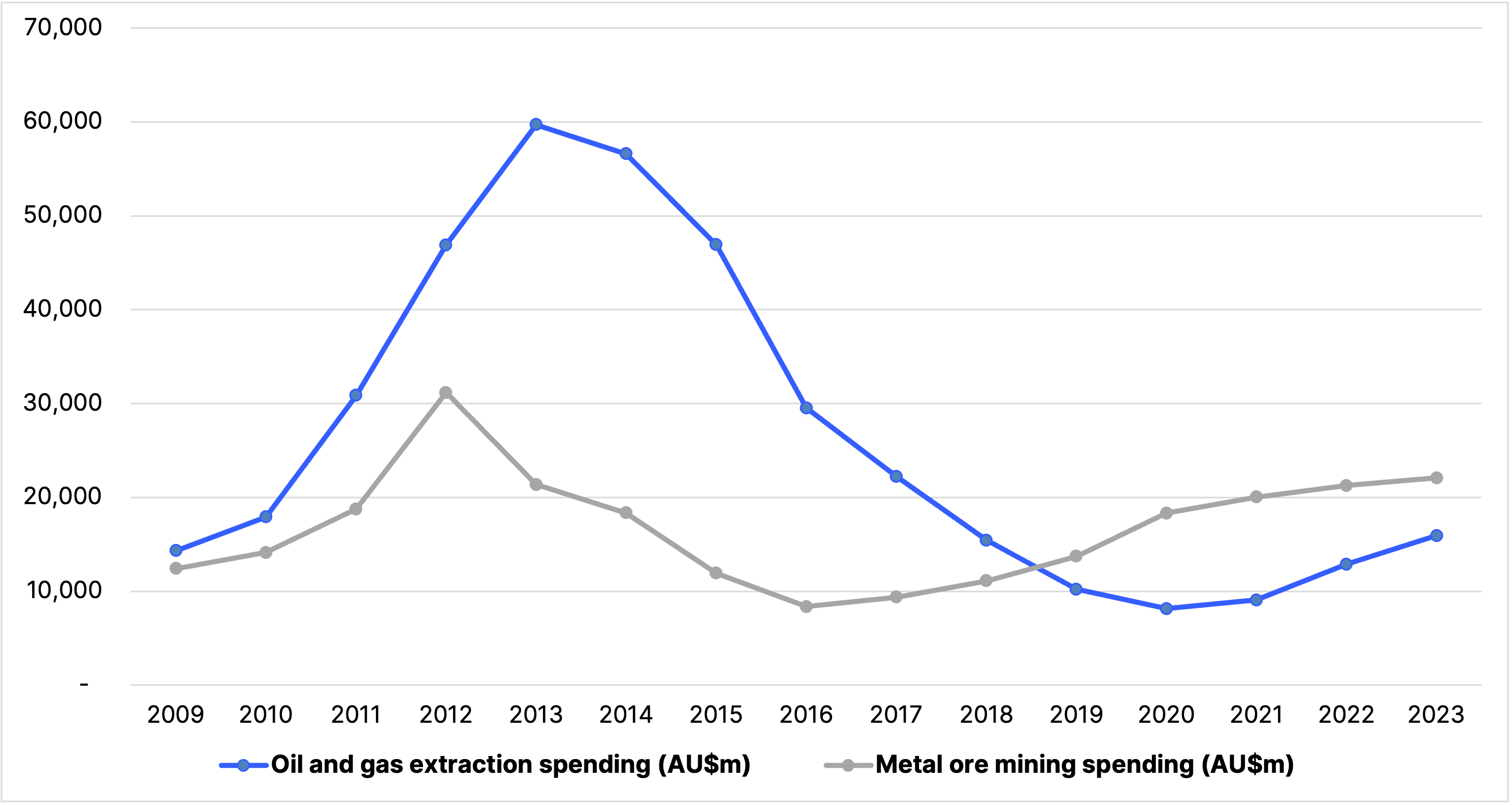

The higher spending on minerals exploration has led to development of new supply of metals needed in the energy transition, with an increase in capex spending. For the past five years, capex on metal production capacity has exceeded spending on oil and gas output capacity. The change in capex spending has been dramatic. In 2013-14, capital expenditure on new oil and gas production capacity, which overwhelmingly reflected new LNG capacity, was AU$60.71 billion. This subsequently fell to a 12-year low of AU$7.42 billion in 2020-21, and was AU$12.41 billion in the first nine months of 2023-24, according to the ABS.

Figure 2: Metals project spending outstrips oil and gas projects, despite rising costs

Source: ABS.

The record spending on new LNG capacity in the first half of the last decade resulted in a tripling of production nameplate capacity to 88.2 million tonnes per annum (Mtpa). The record spending on additional gas supply in the 2013-14 fiscal year was three times the metals sector capital expenditure of AU$19.21 billion in the same period. Nine years later, the metals sector spent AU$20.97 billion on new production capacity last year, compared with AU$14.41 billion on oil and gas production capacity. In 2023-24, spending on metals production capacity is on track to exceed oil and gas spending for the sixth successive year (see Figure 2).

Demand for renewable energy stimulates metals investment

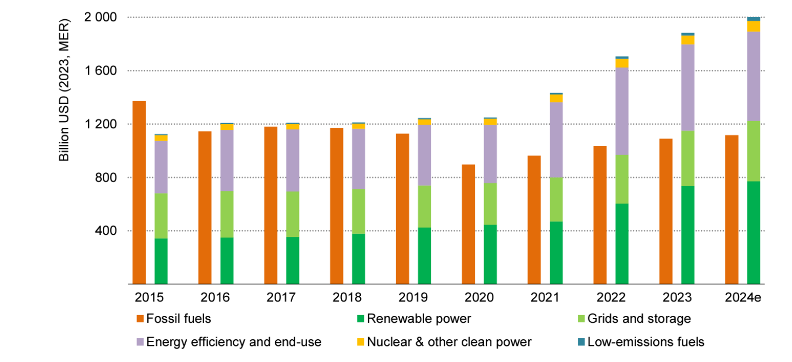

The rise in metals exploration and capital expenditure comes at a time when global investment in renewable energy generation capacity, which are big users of copper, nickel, lithium and critical minerals, has exceeded investment in new fossil fuel capacity.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global energy investment is set to exceed US$3 trillion for the first time in 2024, with US$2 trillion going to clean energy technologies and infrastructure. In its World Energy Investment 2024 report, the IEA states: “Investment in clean energy has accelerated since 2020, and spending on renewable power, grids and storage is now higher than total spending on oil, gas, and coal.”

Figure 3: Global investment in clean energy and fossil fuels, US$bn

Source: IEA.

Industry says one thing, does another

The decline in petroleum expenditure – largely on gas in Australia as we rely on oil product imports for road transport fuel – runs contrary the industry narrative that Australia needs more gas. If this were the case, presumably gas producers should be spending more on exploration.

This is a point Australia’s Office of the Chief Economist (OCE) made in its latest Resource and Energy Quarterly (REQ) report in March 2024: “Gas exploration has been persistently low for the last five years and there is a risk that the current pipeline of gas projects under development becomes insufficient to offset declining reserves. Several projects are likely to start running short of reserves in the next 5-10 years, including the large North West Shelf project in Western Australia. There is potential for the North West Shelf to be supported by third party gas, which operator Woodside and its partners are attempting to secure. However, falling reserves will affect a wider array of projects over time, and higher domestic gas use (driven by the closure of domestic coal plants) could put pressure on supply.”

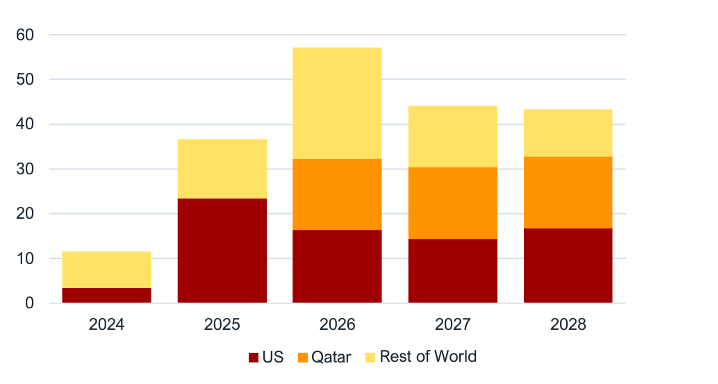

There is also the prospect of a global LNG glut from 2026, given the world is undertaking its largest-ever expansion. IEEFA estimates that 193 Mtpa of new LNG supply capacity could be added globally from 2024 through 2028, a 40% increase over the period. Furthermore, the IEA forecasts an oil glut by the end of the decade, which in turn would impact gas prices as most of the world’s LNG contracts have an oil price link. A scenario of weaker gas prices and surplus supply may influence future gas exploration and development spending.

Figure 4: Global LNG supply additions 2024-2028, Mtpa

Source: IEEFA estimates, based on data from the International Gas Union, the International Group of Liquefied Natural Gas Importers, Independent Commodity Intelligence Services, Kpler, Global Energy Monitor, company announcements and financial filings, and news reports.

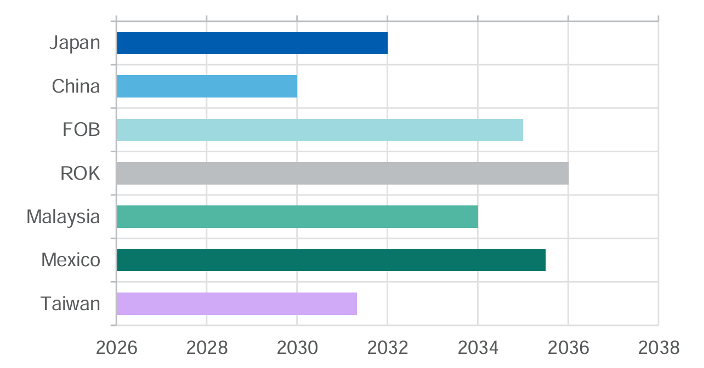

The gas producing sector has shown reluctance to embrace the energy transition, instead advocating for more gas production in Australia – even though around 80% of its output is either exported as LNG or used to produce LNG. However, the government’s Future Gas Strategy Analytical Report notes that Australia’s LNG exporters will see much of their existing long-term LNG contracts expire by 2036 (see Figure 5).

The timeline associated with developing LNG projects from discovery to production is often measured more by a decade. Therefore, the lack of exploration spending suggests one of two possibilities. Either LNG producers are confident they have sufficient undeveloped gas resources within their portfolios to meet existing contractual obligations and an option to continue producing beyond the estimated contract expiry dates. Or they are looking elsewhere since Australia has less than 2% of the worlds gas reserves, and perhaps the best fields have already been developed.

Figure 5: Average end date of Australian contracts by trading partner

Source: Australian government, Office of the Chief Economist. Note: Only includes contracts that are publicly known.

Perhaps the resource sector is taking the advice from the IEA, which says new gas fields are not needed if the world is to meet its emissions targets – limiting global warming to 1.5°C by 2050. Hence, they are investing more in metals that will be used in the energy transition.

Australia is a key player in metals for energy transition

Australia is a significant producer of metals used in renewable energy infrastructure, including iron ore that is used for wind farms and transmission line towers. Australia is the world’s eighth largest copper producer; the fifth largest nickel producer; and the largest, third largest and fourth largest producer of lithium, cobalt and rare earths respectively.

The Queensland state government noted the increase in base metals spending in its recent 2024-25 Budget. Base metal exploration expenditure in Queensland has been elevated in recent years, particularly for copper, as well as several new or expanded operations that are awaiting a final investment decision.

The Australian government intends to stimulate metals exploration and development spending further through its 2024-25 federal budget measures under its ‘Future Made in Australia’ policy. The government is investing a 10% production tax credit totalling AU$7 billion over a decade for all 31 minerals nominated in its critical minerals strategy, to drive critical minerals processing in Australia.

Given the challenges of the energy transition, Australia’s exploration spending on metals should remain firm to meet strong underlying demand. Therefore, it is important that government policies to encourage further exploration should prioritise these vital metals over oil and gas exploration.