Key Findings

The Philippines has a long history of incomplete LNG import projects and to date a large diversity of industry players with extensive financial capacity and project management expertise—including international oil and gas majors, commodity traders, state-owned oil companies, and regional utilities—have been unable to bring LNG-to-power assets online.

Since there are no available government-backed power purchase agreements (PPAs) or guarantees, investors in LNG-fired power plants will be highly exposed to market risks arising from changes in the commercial and regulatory landscape.

High uncertainty in the Philippines market contradicts the nature of the natural gas industry.

Executive Summary

Natural gas industry players have their sights set on Southeast Asia. The International Energy Agency expects emerging liquefied natural gas (LNG) importers in the region to be the main drivers of global demand growth behind China and India, raising suppliers’ hopes for a tighter global market and higher prices. Many Southeast Asian countries have subscribed to the industry-driven narrative that natural gas presents a viable transition fuel from coal-fired generation capacity to a clean energy future.

The Philippines is no exception. Burdened with the highest electricity prices for residential consumers in the region, a high exposure to volatile global coal prices, and increasingly severe natural disasters caused by climate change, the government has signalled its commitment to transition from coal-fired power. And with the expected depletion of the Malampaya deepwater natural gas development—the country’s only domestic source of natural gas—officials have endorsed a rapid buildout of LNG import infrastructure.

The race to develop LNG facilities in the Philippines has gone from a marathon to a sprint.

The race to develop LNG facilities in the Philippines has gone from a marathon to a sprint. Malampaya is nearing depletion sometime in the mid-2020s, meaning existing gas-fired power plants will need to find a replacement fuel source in the near-to-medium term. Moreover, the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to grow at a high rate of 5-8% over the next decade, adding urgency to the search for new power capacity.

In this context, it is easy to assume that the Philippines’ LNG demand will grow rapidly, and that with government support, investments in LNG-fired power plants and other related infrastructure will face negligible development risks and reap all-but-guaranteed returns.

But the picture is much more complicated. The country’s long history of incomplete LNG import projects should beg the question: What changes have been made recently to overcome regulatory and financial hurdles that have beset conventional projects in the past? To date, a large diversity of industry players with extensive financial capacity and project management expertise—including international oil and gas majors, commodity traders, regasification operators, state-owned oil companies, and regional utilities—have been unable to bring LNG-to-power assets online. Many have made it to advanced stages of project development but to no avail. One project has been over 90% complete for at least five years but has remained offline and stranded due to regulatory delays.

Policymakers have tried increasingly to iron out lower-level administrative hurdles and incentivize investment by issuing permitting rules, publishing investor guides, and proposing legislation to govern the midstream and downstream natural gas sectors. The United States Department of State, through its Asia EDGE (Enhancing Development and Growth through Energy) Initiative, has pushed legal and regulatory reforms to stimulate the creation of a new Philippines market for US LNG exports. Yet the higherlevel legal and regulatory regimes for LNG are still in their nascent stages and could take years to refine and implement, adding uncertainty to the future market environment.

High regulatory and financial uncertainty in the Philippines market contradicts the nature of the natural gas industry.

For the midstream natural gas industry, which is characterized by low profit margins and long payback periods for high-cost infrastructure, stability is crucial to minimizing gas developers’ market risks. Such high uncertainty in the Philippines market contradicts the nature of the industry, especially with almost no existing infrastructure in place.

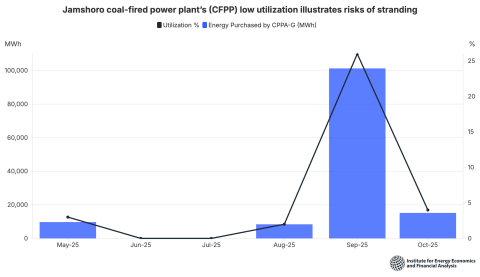

Moreover, the case of the Philippines shows clearly how LNG importers’ reliance on traditional, long-term project financing terms is incompatible with deregulated power market structures being reshaped by rapid technological innovation. Since the country’s landmark 2001 Electric Power Industry Reform Act (EPIRA) banned government involvement in power plant contracting, there are no available government-backed power purchase agreements (PPAs) or guarantees, leaving investors in LNG-fired power plants highly exposed to market risks arising from changes in the commercial and regulatory landscape. As more zero marginal cost renewables come online, gas-fired power plants are expected to be dispatched much less frequently, limiting the predictability and continuous need for large volumes of imported gas.

Given rapidly changing market structures and evolving regulatory regimes, project sponsors and financiers must carefully assess the high risk of stranded assets for LNG projects resulting from idle capacity and reduced operating cashflows.

This dynamic is reflected in the ongoing implementation of Retail Competition and Open Access (RCOA), which allows large and medium power offtakers to choose their electricity providers. As the threshold for consumer choice is lowered, increased competition will put pressure on distribution companies to reduce costs for end-users and could ultimately lead to a reduction in contracted capacity required by large utilities. As a result, distribution companies—now competing with retail suppliers—have become increasingly wary of locking-in long-term LNG price volatility and infrastructure costs.

Imported gas has a small role to play in meeting existing demand from anchor gas plants and possibly for additional peaking capacity from open-cycle gas turbines (OCGT). Large baseload LNG-to-power projects, however, will have diminishing opportunities to win conventionally bankable offtake agreements and will have to bear significant market risk. Although some new LNG-to-power facilities are likely to come to fruition over the next decade, success on a project-byproject basis does not signal a national strategic commitment to gas or guarantee sustainable natural gas demand growth in the medium-to-long term.

There is no existing gas transmission and distribution infrastructure to supply non-power sectors.

Meanwhile, there is no existing transmission and distribution infrastructure to supply non-power consumers. Industrial, commercial, residential, and transport sectors will require massive investment in gas transportation infrastructure, as well as more complicated contracts for smaller gas volumes. Actual LNG demand is therefore highly likely to undershoot analyst forecasts for rapid growth, leaving investors on the hook for unused mid- and downstream capacity.

History rhymes, and barriers to past LNG ambitions in the Philippines are likely to plague the new wave of projects. Similar to Vietnam, unresolved legal, financial, and structural questions are only now coming into focus for LNG project sponsors, even those that appear to be well advanced. These questions will need to be settled before sustainable sources of funding can flow. Potential investors in LNG projects must proceed at their own risk.

Please view full report PDF for references and sources.