IEEFA India: Thermal coal flatlines in faltering economy, power from non-coal sources continues to grow

In the space of just a few days, India’s slowing economy has attracted the attention not only of the domestic press, but of international media including the Financial Times and an Economist special report, which noted that “with alarming speed, India has gone from being the world’s fastest-growing large economy to something more like a rumbling Indian railway train.”

When economies stumble, slackening electricity demand is a very common symptom.

A host of economic indicators have received attention, ranging from the official (World Bank and Indian government growth downgrades) through indices such as Fitch Ratings or LiveMint’s Macro Tracker, to the flippant but nonetheless informative (including the New York Times’ story on underwear sales, or Neilsen’s report of declining toothpaste purchases in rural India).

TO THIS LIST MAY BE ADDED AN ECONOMIC HEAVYWEIGHT: THERMAL COAL.

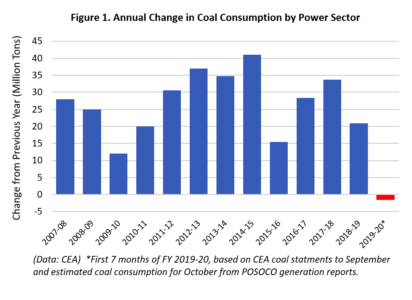

Having held up throughout the summer when other signs of a relative downturn were already apparent, the amount of thermal coal burned for power fell precipitously in September and October. So steep has been the decline that the annual increase in coal consumption by the power sector, which has averaged 6.3% or 27 million extra tons each year for the last 12 years, fell to zero not only for the financial year to date (Figure 1), but also for the full 12 months to 31 October 2019, compared to the previous year.

When economies stumble, slackening electricity demand is a very common symptom. In India’s case, the current decline is quite specific to coal. This is most readily seen by comparing how power generation from different sources has changed across the course of this year relative to last.

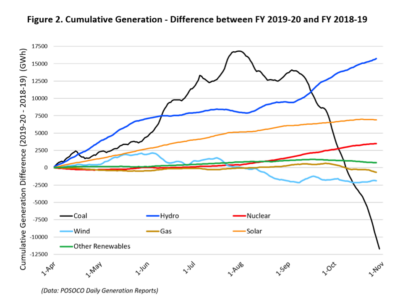

Hydro, solar and nuclear have added substantially to their generation levels of the previous year and continue upwards. Wind started well but the monsoon period was disappointing, resulting in less cumulative generation than at the end of October in FY19. Gas, a minor player, also lagged slightly.

Collectively, power from all non-coal sources grew by about 24,000 GWh or 8.4%, to the end of October. (See Figure 2 showing the cumulative excess (+) or deficit (-) calculated daily from April 1, the start of FY20)

The obvious exception is coal, which had made the largest contribution to extra energy as of late July, only to falter in August and collapse in September and October. As of the time of writing, coal had produced about 12,500 GWh less electricity than it had by the same date in FY19, roughly the amount, for perspective, consumed by Delhi and its 24 million residents in five months.

GIVEN THE SCALE AND SPEED OF COAL’S DECLINE AND ITS DOMINANT GENERATION ROLE IN INDIA, it is noteworthy that overall electricity generation growth remains positive for the year so far, showing the continuing success of the Government of India’s plans to diversify and decarbonise.

Coal’s decline is not primarily the consequence of any shortage of coal, despite claims to the contrary.

Three related points can be made about this abrupt fall. Firstly, it is not primarily the consequence of any shortage of coal, despite claims to the contrary. Power plant stocks are now 8.5 million tons (66%) higher than at the end of October last year when generation was much higher, despite 29 plants having ‘critically low’ stocks (only three plants are in that position today). Not only have the Rail and Coal Ministries succeeded in increasing power plant stocks overall, they have evened out the distribution to reduce the number with only a few days’ supply (even though these now include more high capacity plants).

More to the point, the 77 plants that generated less energy in late October this year than they did a year ago had on average 7.8 more days of stock on hand (using October 28 as the day for comparison and only plants whose capacity was the same in both years).

Thus while specific individual plants clearly do have supply problems because of strikes, weather (e.g. Talcher STPS), the Dipka mine flood, and others (such as Tuticorin JV TPS) are receiving less coal than a year ago, this is not typical. Nationally neither unmet energy nor unmet peak demand has increased. Warnings that a supply crunch threatens to restrict India’s economy by 2024 may or may not eventuate, but they are not today’s reality. Rather, India’s economy appears to be limiting the use of available coal.

The second point is that the duration of the thermal coal downturn cannot be accurately forecast. To the extent it is driven by India’s economic conditions, it could be relatively brief if the economic optimists are correct (such as Gaurav Dalmia, interviewed at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton Business School), or longer-lasting, if we rely on those who see more intractable and structural factors at play. The Economist’s take is that higher growth will largely depend on whether India adopts appropriate economic reforms: “With luck, in a few years’ time, the present slump may be regarded as a useful catalyzing moment.”

THE THIRD OBSERVATION IS THAT THE COAL SLUMP OFFERS INDIA AN UNUSUAL OPPORTUNITY. While not under pressure from burgeoning electricity demand growth, India could fortify its necessary energy transition plans, reduce the country’s 1.2 million annual air pollution-related deaths, and stimulate urgently needed rural job growth, all while enhancing India’s energy security through greater domestic capacity.

This could include a revival of large-scale renewable infrastructure investment in preparation for sustained higher growth, while accelerating the HVDC Green Corridors and plans for the Flexible Operation of Thermal Power Plants, as well as new projects built on the comprehensive and collaborative Grid Integration studies India has developed.

As India presses forward with its renewable energy transition, as and when higher economic growth does resume, it will be fueled by substantially cleaner energy than in the past.

Charles Worringham is a guest contributor with IEEFA South Asia. He edits India Power Review.