Financial risk in Australia's coal ports

Download Full Report

Key Findings

Banks and credit ratings agencies’ outlook for coal terminals is outdated amid the ongoing climate transition and higher risks facing coal mining. Despite these trends, they continue to maintain positive credit outlooks and provide debt financing for Australia’s coal ports.

New coal projects are increasingly difficult to finance and approve, and new coal supply will not keep pace with declining volumes from existing mines.

In periods of depressed demand, marginal coal miners may cease production, leaving the remaining operators to cover higher port costs.

Climate change risks continue to add financial burdens to the coal export supply chain and are only set to worsen over time. The risks to ports are not independent to those faced by miners.

Executive Summary

Coal ports were once regarded as stable fixed-income investments, but this is increasingly not the case.

Investments in infrastructure like ports and railways have historically been seen as dependable, low-risk assets. Recently, credit ratings agencies have been showing renewed confidence in Australia’s coal export terminals.

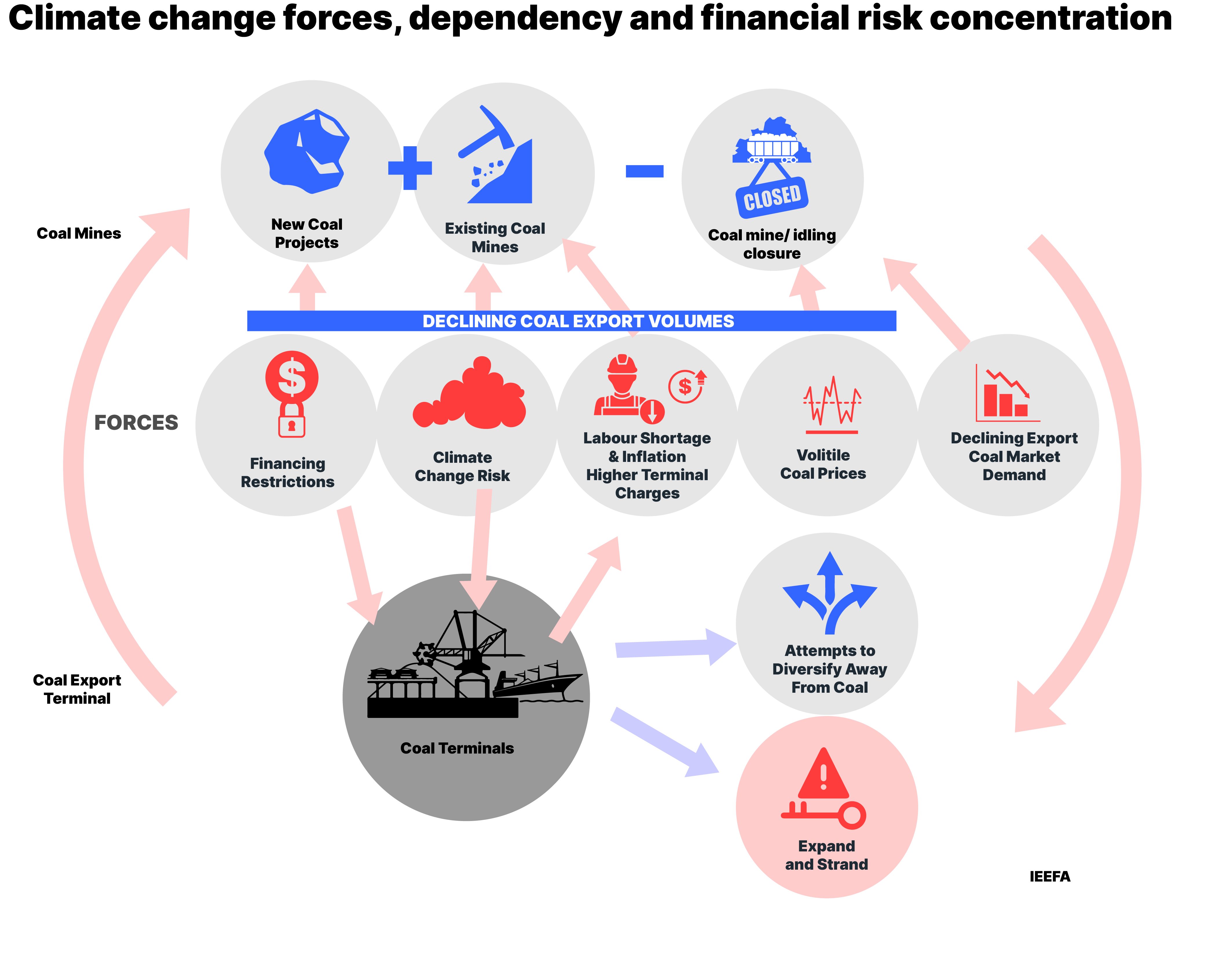

A new set of risks are arising and converging to magnify the counterparty risk throughout the entire coal supply chain, driven by high coal price volatility combined with climate change and the energy transition.

However, it’s no longer viable to treat coal mines and their export ports as distinct industries with independent cash flows and creditworthiness. A new set of risks are arising and converging to magnify the counterparty risk throughout the entire coal supply chain, driven by high coal price volatility combined with climate change and the energy transition.

The rising costs of terminal charges are adding to coal miners’ cost inflation woes. Mining labour shortages curtail expansion plans and increase unit production costs. Extreme climate events risk damaging infrastructure and disrupting supply, while trading-partner decarbonisation policy measures will reduce demand. With increased pressure to meet higher financing costs, circular dependencies are driving a concentration of risk across the sector, as shown below.

- Export coal volumes delivered to ports are a function of the addition of new mines to replace depleted or idled mine production. The Australian government expects supply of both thermal and metallurgical coal to decline. New mine approvals are constrained and some miners such as BMA, owner of Hay Point Coal Terminal, say they will not develop any new coal projects in Queensland. When served by multiple port alternatives, there are also competitive forces attracting miners to secure port capacity on the most favourable terms.

- Financing restrictions from traditional banking sources are forcing coal miners to look to higher-cost alternative lenders. The banks’ climate-policy exclusions are currently aimed at coal mines and coal power stations but could in future extend to coal infrastructure, which is highly leveraged and faces greater refinancing risks if exclusions are widened.

- Climate change risk is currently assessed separately for coal miners and for transport infrastructure such as ports. However, supply chain infrastructure from coal pit to port is geographically concentrated such that an impact to part of the chain affects the whole system. The less obvious policy-related climate change risks entail emissions reductions efforts both at a mine level and of our trading partners.

- Labour shortages and other cost inflation are impacting coal miners. Port terminal charges have also increased, adding to miners’ fixed operating costs. While recently these pressures have been masked by record prices, they will erode cashflow margins in periods of depressed prices.

- Volatile prices are being experienced in both thermal and metallurgical coal markets. A downturn would squeeze margins of the highest cost producers and risk further decline in port volumes. In the long term, the port will seek recovery of fixed costs from the remaining shippers, in turn raising their costs. It’s an interdependent system.

- Declining export coal demand risks are accelerating. Financiers and ratings agencies seem to hold the view that strong demand for Australian (premium) coals will persist well into the future. Their assumption that any gap left by a departing miner will be readily filled by a newcomer needs to be examined in the light of a structurally declining coal market.

- Coal terminals are experiencing declining export volumes in FY2023. However, the risks to coal terminals are often considered immaterial as their capacity is covered by take-or-pay contracts to coal miners, transferring the volume risk to the miner (shipper). But there is an interdependence between the two, even though banks and rating agencies appear to consider them separate industries.

- Attempts to diversify to expand non-coal future revenues in response to lower coal throughput and transition risks are being widely considered. On the rail infrastructure side, Aurizon has embarked on a strategy to grow its non-coal revenues.

- Expansion of coal infrastructure is being considered by some in light of optimistic demand regarding new coal projects. While not surprising, commitments to sign up for long-term supply contracts are no guarantee of success. At the Wiggins Island Coal Export Terminal (WICET), only three of an original eight bullish shareholders remain – the rest are insolvent or otherwise paid out their commitments.

Australia’s coal export terminal throughput is running well below capacity and declining. While the volume risk of lower throughput is generally transferred to the coal miners – through take-or-pay arrangements or shareholder agreements – this underutilsation can lead to several adverse outcomes. Ports located in urbanised areas may have more success in diversification than those in remote regional locations due to their greater flexibility to adapt infrastructure to meet growing demand for containerised shipping. Following record profits in 2022/3, established miners have paid down debts and returned funds to shareholders. This is in contrast to new junior miners, who might be expected to have a higher probability of default (PD) in the event of a downturn.

Investors are increasingly requiring companies to account for their emissions amid growing public concern over climate change. Scope 3 emissions, from the burning of our exported coal, are more extensive than Scopes 1 and 2, which occur within our domestic shores. As a visible symbol of exported emissions, coal ports in particular face an elevated risk, as Australia’s environmental accountability may encompass these downstream Scope 3 emissions in future.

Banks are increasing their climate-related disclosures; setting targets for fossil-fuel exits; sharpening environmental, social and governance goals (ESG) policies; and greenwashing. ESG policies and scores need to be reworked to reflect climate risk and financial risks. Coal ports are highly leveraged and as such face greater refinancing risks if exclusions are extended further. Banks’ coal exclusion policies need to be robustly reworked to exclude coal capacity investments along the entire value chain – mining, power generation and transport infrastructure.

How governments leverage this opportunity as well as addressing the challenge of achieving net zero emissions by 2050 remains uncertain. It seems unlikely to be accomplished by supporting developments of long-lived port assets that facilitate fossil fuel exports. Responses to these challenges by financial market regulators, banks, insurance companies, super funds and governments need to accelerate.