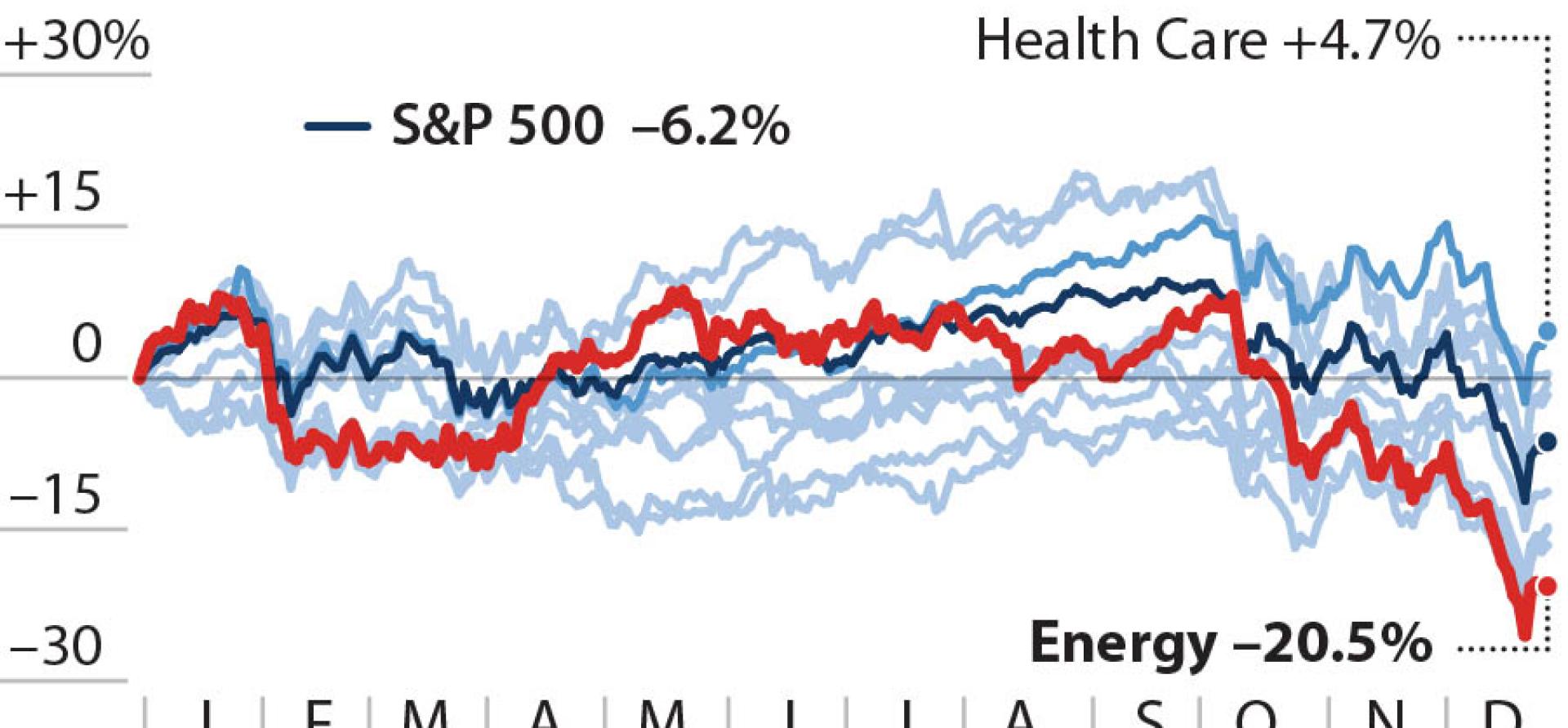

IEEFA update: 2018 ends with energy sector in last place in the S&P 500

The stock market went to hell in December. And when it got there, it found that the energy sector had already moved in, signed a lease and decorated the place.

One cannot minimize the impact of the overall year-end market decline on energy sector stocks, which went down along with every other sector. For example, Apple’s market cap declined from $1.1 trillion in June to $750 billion at the end of the year. That loss alone is more than the current market cap of ExxonMobil, the largest U.S. oil and gas producer.

But here we are taking a look at the full year of 2018, including where the impact of the market downturn ends and where instead oil and gas sector fundamentals explain the sector’s poor investment performance.

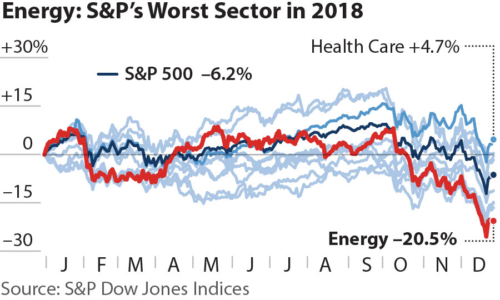

The bottom line: for the second straight year, the stock performance of the energy sector was at or near the bottom of the S&P 500 – and in 2018, it was solidly in last place.

The bottom line: for the second straight year, the stock performance of the energy sector was at or near the bottom of the S&P 500 – and in 2018, it was solidly in last place.

In early 2017 and 2018, the industry buzz had oil and gas primed for a comeback. The oil price rise, which started in early 2016, sent Brent crude oil prices from $29 per barrel in January 2016 to a peak of $85 per barrel in January 2018. And the chatter was that it was going to reach $100 soon thereafter.

During this oil price run-up, it looked like the energy sector would show overall improvement. Integrated oil and gas companies posted cash gains and many quarterly profit reports topped estimates. If you invested $1,000 in ExxonMobil on March 28 and sold it on October 9, you walked away with a $131 gain.

No lift from rising oil prices.

But October brought an early frost in the oil market and the Brent limped off at $54 per barrel at the end of the year. So if instead you had invested $1,000 in ExxonMobil on January 1 and held it the whole year, you were looking at a $200 loss. Even at its high point, ExxonMobil never meaningfully surpassed the S&P 500, although the industry index as a whole did so for part of the year.

Developments in 2016 had suggested that maybe oil and gas companies would mount a comeback to their former place of global leadership. But 2017, and now the end of 2018, have shown us something different: oil and gas would lead the way down. In the last quarter of 2018, oil and gas stocks fell more steeply than the SP 500 and ultimately more than any other sector.

Within the energy sector, the integrated oil and gas companies were not the only ones having a hard time. In 2018, the stock of the unconventional oil and gas companies that specialize in hydraulic fracturing (fracking) lost 30% of value, and the oil and gas supply companies lost more than 40% . The fracking boom has produced a lot of oil and gas, but not much profit. Complaints by the industry that their poor performance is in part related to pipeline capacity constraints were contradicted recently by Wall Street Journal coverage that there is no shortage of pipeline capacity, in fact there is too much capacity. The problem is that industry planners spent hundreds of millions putting pipelines in the wrong place.

The down cycle for oil and gas suppliers means that development costs are lower now, which has been a key driver of the rationale for ExxonMobil’s subsidiary Imperial Oil’s decision to reinvest in Canadian oil sands. On the other hand, weak profits are putting the brakes on oil service provider interest in Argentina’s Vaca Muerta shale play.

Analyzing the short term gyrations of the oil markets these days quickly leads to analyzing the deteriorating quality of oil and gas investments. Short-term gains in the industry would be acquired with all the certainty of buying a winning lottery ticket. The medium term strategy of squeezing every last nickel out of existing reserves offers slightly better odds, more like playing poker. And OPEC, Russia and U.S. producers disrupt as they posture for dominance.

BEHIND THE CURRENT TUMULT LIES A LONG-TERM DOWNWARD TRAJECTORY. THE OUTLOOK IS DECIDEDLY NEGATIVE.

OPEC is consistently hampered by its own internal contradictions and weaknesses. Cutting production is the only way to prop up prices, even a little. $50 and $60 per barrel is better for the government budgets and “oil-garchs” than $30 or $40 per barrel. But flirting publicly with pushing for higher prices – and then failing to do so — only reinforces the weaknesses of authoritarian leaders and company balance sheets. For OPEC and other players, a larger investment in activity that generates lower profits is about as good a result as it can expect these days.

U.S. oil producers on the other hand are now the biggest oil suppliers globally, with capacity exceeding 12 million barrels per day. They can quickly fill supply gaps, profit from rising prices, and just as quickly tamp down price spikes with supply gluts. OPEC has already tried to do an end-run on U.S. producers with a glut of Mideast oil, expecting lower prices to diminish U.S. producer profitability and investment. But it hasn’t worked. For better or worse, U.S. capital markets manage the mass investor casualties of sector-wide bankruptcies with the skill of a battlefield MASH unit, with triage techniques that allow the drilling and pumping in the U.S. to continue.

OPEC’s bullish potential resides with the political destabilization of Venezuela and Iran, but this is not a very promising strategy. In the short term, U.S. producers can fill any gap in supply, frustrating OPEC’s quick cash ambitions. Long term, the potential for extended political destabilization and market disruption in both countries is not at all clear, despite tweets, OPEC’s internal politics, and domestic political tumult in each country. Although each scenario comes with the vagaries of political intrigue, the results will be to push production up and prices down.

The demand side has historically given the oil and gas sector a happy face. But demand is now increasingly roiled by slower and less energy-intense economic growth, by market penetration from renewable energy alternatives, by energy efficiency, by new storage technology and by more limited use of automobiles.

The industry’s rush to invest in petrochemicals to maintain demand for oil and gas is likely to continue, but the profit potential in this sector is more limited than oil and gas exploration, and is likely to keep the energy sector at or near the bottom of the S&P 500.

THE ROAD FORWARD WILL NOT BE SMOOTH. Despite the general pressures toward downward prices, there will be price spikes and thus the potential for short term profits for some producers. On the other hand, expect stronger political responses to higher prices from consumer countries with high oil dependencies. Some will object; some will promote policies to accelerate away from fossil fuels. And those countries that are both producers and consumers may face renationalization initiatives as global demands disrupt stabilization of domestic energy markets.

2018 saw oil and gas stocks act like highly speculative, commodity niche investments. The investment pitch to investors now is quick cash, quarterly payouts and fast talk. Given the sector’s volatility, the loss at the end of the year could just as easily have been an uptick. Either way the stocks lack a long-term value rationale.

Oil company investments used to be blue chip stocks – characterized by steady, stable profit generating companies, who push the market up during periods of growth and slow the market’s trajectory on the way down. But the low-priced, volatile, oil and gas market, punctuated by significant geopolitical realignment, greater competition, a weak business model and public opposition, is no longer a blue chip investment.

2019 will probably begin with a call to “buy,” as the oil and gas market has gone to hell and, it will be said, is therefore likely to rebound. But investors would be wise to remember that the energy sector has a long-term lease on that location.

Tom Sanzillo ([email protected]) is IEEFA’s director of finance.

RELATED ITEMS:

IEEFA Update: The Many Risks in Rising Oil Prices

IEEFA update: Whether prices are high or low, the oil and gas industry is freighted with risk

IEEFA U.S.: ExxonMobil goes back large into risky Canadian oil sands