IEEFA U.S.: Cloud Peak bankruptcy reflects the coal industry’s slippery slope

In yet another sign of steep decline and restructuring across the coal sector, Cloud Peak Energy, the fourth-largest U.S. coal mining company in 2018, filed for bankruptcy on May 10. It is the second major coal producer to do so in less than a year, following Westmoreland Coal, which was the 10th-largest U.S. coal producer in 2018 (now called Westmoreland Mining after emerging from bankruptcy in March).

Cloud Peak’s three mines—Antelope Coal, Cordero Rojo and Spring Creek—are all located in the Powder River Basin (PRB), the country’s most productive coal region, which straddles eastern Montana and Wyoming. But this area, which produced more than 40 percent of all U.S. coal last year, is also facing serious and growing economic challenges and technological competition that will likely alter the industry fundamentally in coming years (see our March report, Powder River Basin Coal Industry is in Long-Term Decline).

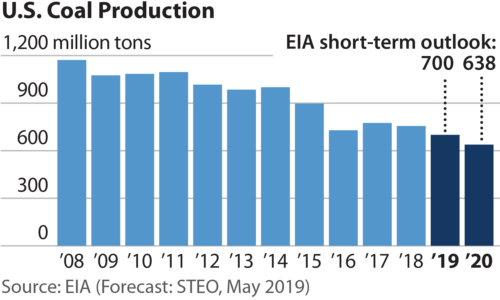

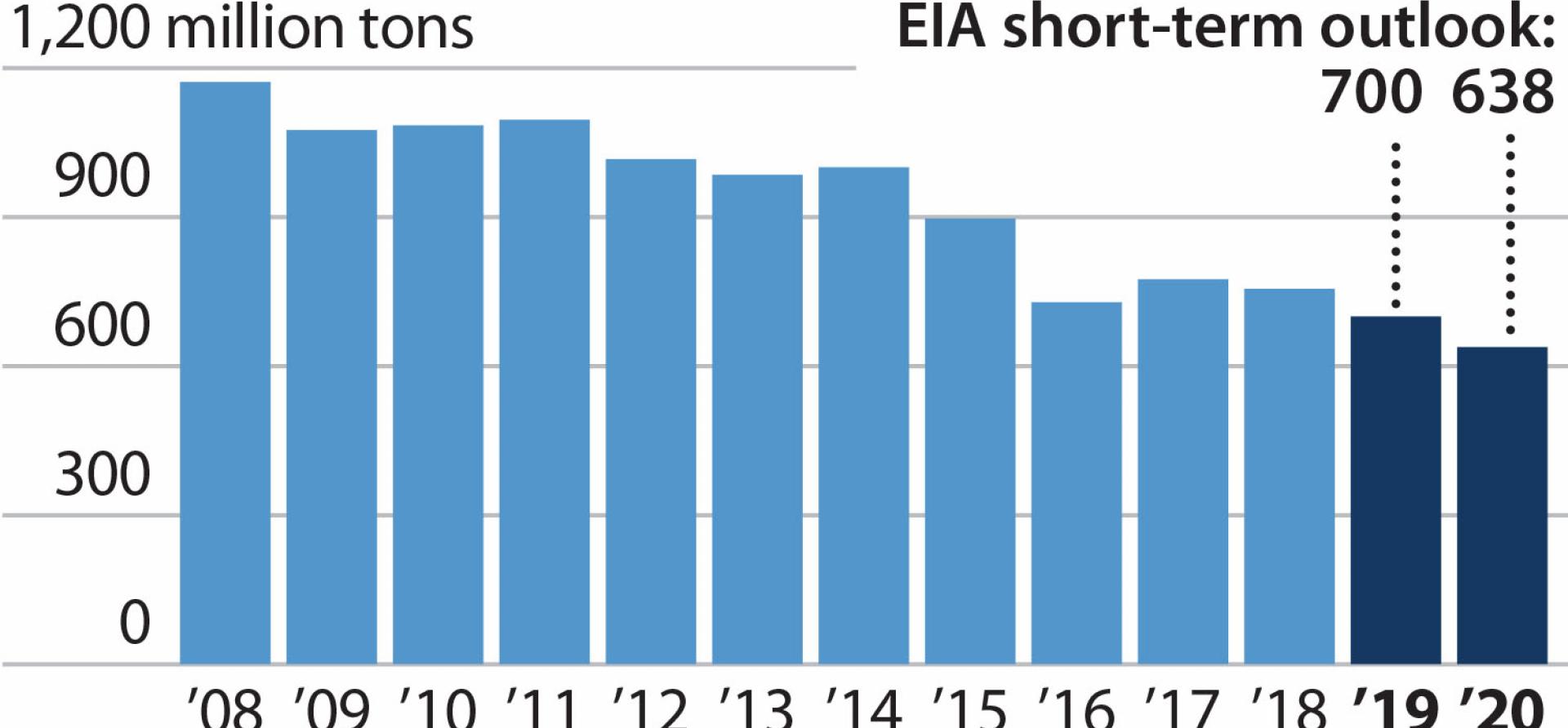

The decline of PRB mining has been rapid, and is set to accelerate. Only a little more than a decade ago, in 2008, output at PRB mines reached 496 million tons —nearly 80 percent of all coal mined in the Western U.S. and 42 percent of the record 1,172 million tons produced in the U.S. that same year.

Plants are closing at a record pace and existing units are operating less and less frequently.

But that production peak came just as generation from wind and solar was starting to take off; the boom in natural gas from fracking was getting under way; a decade of flat demand for electricity was on the horizon; and power customers both large and small were beginning to demand cleaner sources of energy.

The result of all these trends? Coal’s market share for power generation halved, from close to 50 percent in 2008 to a projected 24 percent this year.

THIS DRAMATIC DECLINE IS SIGNIFICANT TO THE INDUSTRY, since the vast majority of American coal is burned to generate electricity. Utilities retired coal-fired power plants at a record pace last year and have been using many of the remaining coal units less and less frequently, a trend likely to continue, and one that will perhaps even speed up. As a result, analysts at the Energy Information Administration (EIA), part of the U.S. Energy Department, expect total U.S. coal production to fall to just 638 million tons by 2020—a decline of 120 million tons in just two years, down 534 million tons from the 2008 peak. Coal consumption is forecast to fall even further, by nearly 130 million tons, to 560 million tons in 2020.

This year alone, American coal production will fall by 7.2 percent, by the EIA’s latest assessment.

THE ECONOMICS OF BURNING COAL FOR POWER GENERATION ARE WEAKENING, a trend driven by several forces and made obvious across a host of metrics. Among them:

- The cost to build new solar and wind generation continues to plunge, to the point where shutting existing coal-fired capacity and replacing it with new renewables could save tens to hundreds of millions of dollars, as shown in a recent PacificCorp0 study of its coal fleet.

- Existing solar and wind is almost always the lowest-cost generation source in competitive markets now, pushing out higher-cost resources like coal and nuclear—and sometimes even natural gas-fired generation. In Indiana, state regulators recently rejected a proposal by the utility Vectren to build a new gas-fired plant to replace an old coal-fired plant, ordering the conglomerate to get in better step with “rapid technological innovation” that is propelling the growth of renewables. Even more recently, Southern California Edison scrapped plans for a natural gas-peaker plant, replacing it with a 100-megawatt solar farm that will charge what will be one of the two biggest utility-scale batteries in the world.

- Continuing low natural gas prices and lower operating costs often make gas generation units more competitive than coal units. In Florida, Lakeland Electric recently confirmed that its coal-fired unit at the C.D. McIntosh Jr. Power Plant costs $20 a megawatt-hour more than its nearby combined-cycle natural gas-fired unit.

- New coal plants are far more expensive than other options. Lakeland Electric, for instance, said that replacing the coal unit at McIntosh with a new one would cost at least three times as much as a new natural gas unit.

- The majority of coal-fired units operating in the U.S. were built between 1965 and 1985, making most of them 35 to 55 years old, and experience has shown how operating costs at aging plants tend to rise over time. Further, some long-deferred costs, such as cleaning up coal ash, are under greater scrutiny by utilities as they evaluate the true cost—externalities included—of their traditional generation mix.

These and many other factors are pointing to momentum in the national shift in electricity generation that is leaving coal behind. With demand constantly shrinking and the number of customers dwindling, it is unlikely that Cloud Peak’s bankruptcy, like Westmoreland’s before it, will be the end of the stark restructuring that the sector is facing.

Seth Feaster ([email protected]) is an IEEFA data analyst. Karl Cates ([email protected]) is an IEEFA research editor.

RELATED ITEMS:

IEEFA U.S.: Seeds of a just coal transition policy in Colorado

IEEFA U.S.: April is shaping up to be momentous in transition from coal to renewables

IEEFA U.S.: Post-coal cleanup could be a job-creating lifeline for Colstrip, similar communities