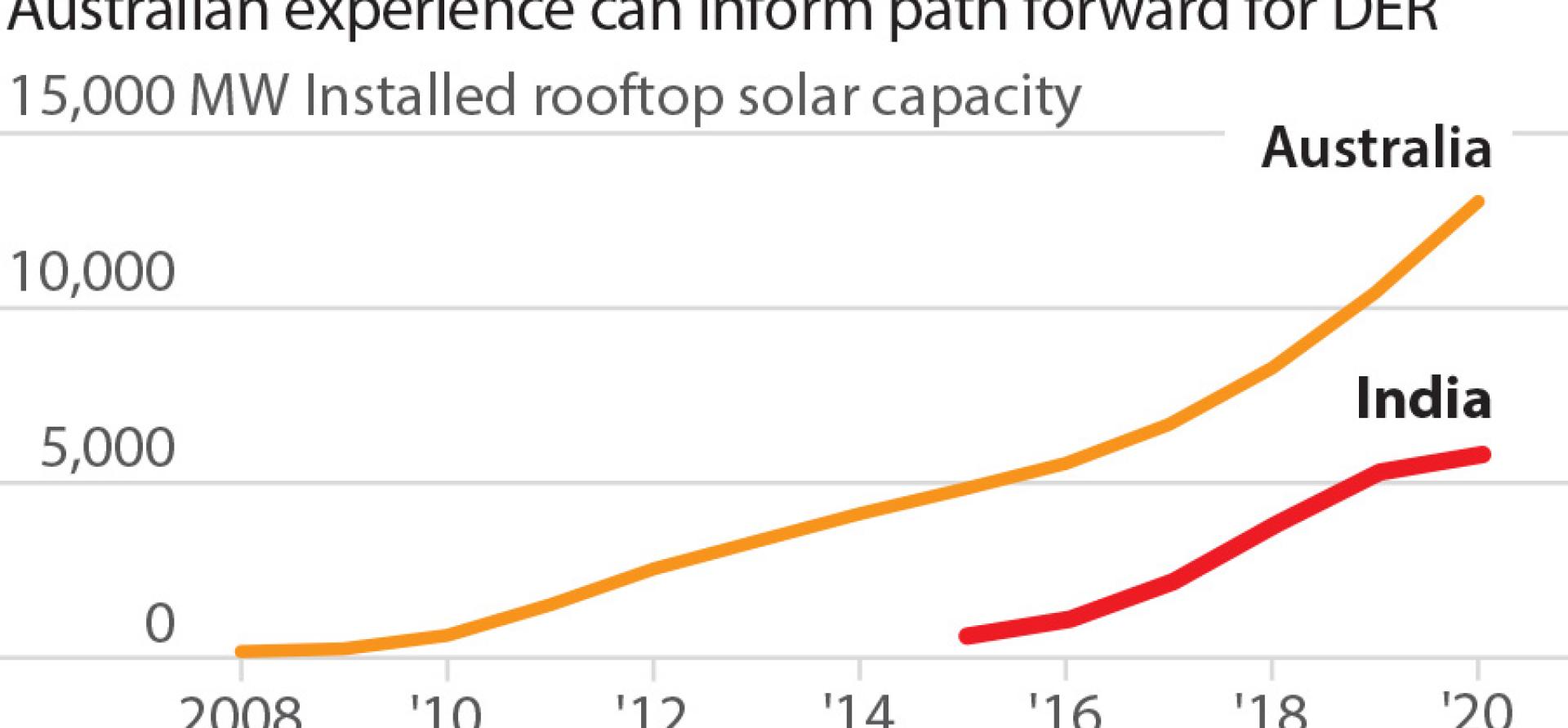

Lessons from Australia for India on integrating distributed energy resources

Download Full Report

Key Findings

The integration of Distributed Energy Resources is worthy of serious policy attention as an enormous opportunity for India.

Ensuring up-to-date technical standards are in place for technologies such as inverters, electric vehicle charging and appliance demand response is vital.

Indian distribution companies (discoms) could look at developing dynamic operating envelopes, particularly in leading areas of growing rooftop solar penetration.

Executive Summary

While most of the policy focus in India, as elsewhere, has been on large-scale renewable energy, the Government of India has set a target of 40 gigawatts (GW) of installed rooftop solar (RTS) capacity by 2022 to improve energy security, reduce land use strains, better strengthen the national grid, improve air quality and reduce user costs. The government has also undertaken significant measures to support the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) and energy efficient lights and fans. State governments are also supporting the uptake of Distributed Energy Resources (DER) including rooftop solar and solar irrigation pumps. This report puts the case that the future of RTS is rooftop solar plus storage—either in the form of batteries or electric vehicles.

For all the above reasons and more, the integration of DER is worthy of serious policy attention as an enormous opportunity for India. This report looks at what can be learnt from the integration of DER in Australia so far and how it might better inform India’s investment program. We discuss technical, regulatory and market integration of DER, arguing that technical integration is the first priority. Technical integration work is vital to support consumer and investor confidence in DER in India. This encompasses the quality of DER products and installations, integration into the distribution grid and providing certainty of return on investment.

The future will be rooftop PV with battery storage/electric vehicles.

The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) has established a DER Register which collects information on DER devices such as rooftop solar, batteries, EVs, air conditioners and pool pumps at the time of installation. Australian distribution businesses have been trialling a number of technologies and data sources to give them greater visibility of low voltage (LV) networks. Greater visibility of LV networks, including through smart meters or equivalent devices is important for the efficient and effective management of multi-way flows.

Ensuring up-to-date technical standards are in place for technologies such as inverters, EV charging and appliance demand response is vital. These standards are best set in a way that involves industry, consumers, distribution businesses, Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs), the system operator (POSOCO), the Ministry of Power and others. In Australia quality control of solar modules and installations has been regulated via subsidy schemes.

Probably the most important innovation in managing DER in Australia has been the development of dynamic operating envelopes (DOEs) which vary import and export limits over time and location, based on the available capacity of the local network or power system as a whole. Indian distribution companies (discoms) could look at developing the capacity to create DOEs, particularly in leading areas of growing RTS penetration.

In planning for DER integration, policy makers and discoms should be wary of scaremongering about the technical impacts of DER. This report details the example of how there have been considerable concerns about the potential for RTS to cause significant voltage rises on the distribution networks in Australia. Speculative concerns have not been borne out by quantitative analysis or real-world experience. India can learn to watch out for these spurious arguments and try to leapfrog into a system where DER is central, planned for and taken advantage of.

In terms of regulatory integration of DER, energy efficiency comes first to optimise the return on any investment in on-site generation or storage. Australian policies, especially for minimum efficiency standards for rental properties and minimum energy performance standards and compulsory labelling of the energy efficiency of appliances, lighting and equipment are worth noting—particularly given the expected urbanisation of the Indian population over the coming two decades.

A wholesale demand response mechanism (DRM) will commence in Australia in 2022. Demand response will need to be in a different form in India given that only a still small volume of electricity generation is traded in the real-time market, but nevertheless, it needs to be a priority for policy makers and discoms to assist in the optimal development of a national electricity market. The increase in air conditioning load predicted for India by the International Energy Agency (IEA) suggests that a clear price signal is key to ensuring demand-responsive air conditioners and converting existing air conditioners to be able to be remotely controlled by a discom is a policy ripe for development.

India can leapfrog into a system where DER is central, planned for and taken advantage of.

Next, data regulation is important, especially where consumers are able to own and easily access their data for use in choosing services or purchases, such as RTS. The introduction of a time-of-day pricing signal would be valuable because consumers could use data directly or through a third-party to vary/optimise their demand.

Performance-Based (or outcomes-based) Regulation (PBR) is a means to align the objectives of the network owners with the social and decarbonisation policy objectives and is well suited to DER integration. Australia has yet to move to PBR but has a multi-year revenue cap for discoms which could be considered for India. Other outcomes that could be contemplated for Indian discoms are promoting discom-led RTS, solar+storage and RTS+EV offerings, and financing discoms to develop EV charging stations at the most appropriate locations in their grids.

Complementary to PBR is innovation funding. The Australian Renewable Energy Agency, similar to the Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency, has developed a Distributed Energy Integration Program which has been very helpful in catalysing DER-related research, trials and policy development.

Finally, for market integration of DER policy makers should endeavour to keep a relatively steady rate-of-return for RTS and batteries as installation and financing costs fall and circumstances change.

Innovative financing models such as the First Loss Portfolio Guarantee and the Partial Risk Guarantee Fund should be explored as alternative mechanisms to de-risk the sector. IEEFA recommends that the Indian banks and financial institutions enhance the disaggregation of their portfolios between thermal and renewable energy assets and have separate lending allocations. Further, within the renewable energy sector, separate allocations should be provided to RTS and small-scale storage/EVs. In addition, banks should give concessional loans to RTS as the market is small and still needs financial support, leveraging the existing US$625m investment program of the World Bank and the State Bank of India which is nearing the end of its five-year mandate.

As the Indian duck curve develops, time-of-day tariffs could be an increasingly useful tool for balancing demand with increased low cost but variable supply.

Timely and smart technical standards are vital, especially for energy efficiency and demand response.

South Australia Power Networks introduced a new middle-of-the day ‘solar sponge’ tariff at a quarter of the standard rate from 1 July 2020. India has the opportunity to learn from the results of this and other tariff enhancements internationally, enhancing the low emissions, smart electricity grid of the future.

Likewise, there is no need for India to rush into DER aggregation policy or trials until there are higher penetrations of RTS, storage and EVs.

India has an opportunity here to learn from Australia’s mistakes and successes and focus first on the most important technical and regulatory measures for DER integration.