European oil: Navigating credit risk towards net zero

Download Full Report

Key Findings

A long-term credit ratings view should be applied to oil and gas companies to account for the unprecedented sector-wide exposure to transition risk, as observed from the case of European firms.

Credit rating agencies’ methodological approach does not systematically integrate asset stranding risk and competition from low-carbon technologies faced by the European oil and gas sector.

Despite the short-term focus of credit financial modelling, rating agencies are well-placed to better utilise their qualitative levers to account for rising climate-related credit risks.

Integrating assessments of oil and gas company transition plans into final credit ratings will help ensure the relevance of ratings as investors navigate climate-related transition risks.

Executive Summary

The oil and gas value chain is one of the most exposed sectors to energy transition risk. This view is increasingly echoed by the big three credit rating agencies (CRAs): Fitch, Moody’s and S&P. In Europe – this paper’s region of focus – technological, market, societal and regulatory trends add structural pressures to oil and gas demand, presenting substantial credit challenges to the entire sector.

In 2021, S&P took multiple negative rating actions on oil majors, clearly citing the energy transition as a driver – a prominent move, in IEEFA’s view, that highlights S&P’s concrete action to incorporate the energy transition into final credit ratings. Meanwhile, Moody’s and Fitch have used new scoring tools to indicate any potential credit impacts of environmental, social and governance factors. They have also clearly cited the energy transition as a constraint for upgrading European oil majors’ ratings. These moves have substantiated the agencies’ increasing warning signs of long-term business risk faced by the oil and gas industry.

But these efforts do not extend to a systematic integration of climate-related risk in final ratings and outlooks. This remains constrained by relatively short-term rating horizons, where the rating tends to measure an issuer’s repayment ability for up to three years. It can sometimes be challenging to incorporate or predict severe, sudden credit events in financial modelling. However, considering the material role the oil and gas industry plays in the widespread and irreversible impact of climate change, taking a long-term credit view necessitates treating energy transition risk as a distinct risk factor. Any short-term credit view that causes bond mispricing could result in investor losses.

CRAs’ “through-the-cycle” approach leads to largely steady ratings in the European oil sector, despite inherent oil price volatility, which has recently been exacerbated by COVID and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. However, the approach may not fully reflect a structural shift. Risk integration involves considering climate scenarios. For example, the International Energy Agency’s three scenarios offer a wide set of choices – each with varying degrees of ambition and implementation – for governments and companies. All scenarios give a predominantly negative outlook for oil and gas, regardless of whether the world experiences an orderly or disorderly energy transition.

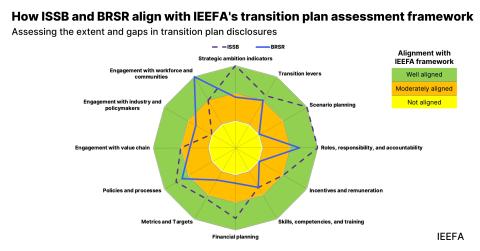

CRAs could take reasonable steps to leverage their existing toolkits to foster a long-term view qualitatively. For example, considering sector-wide industry headwinds could explicitly account for low-cost alternatives enabled by technology. Also, assessing an issuer’s capital requirements amid climate change could include how these interplay with the company’s recent record of shareholder remuneration and its fossil fuel and renewable investment splits. IEEFA recognises that CRAs have made significant progress in developing dedicated – albeit separate – tools for assessing transition plans, making the agencies well-positioned to take gradual steps to formally apply these assessments to final credit ratings.

IEEFA further recommends that CRAs should regularly enhance their sector-specific rating criteria with more coherent, explicit risk integration in the assessment process. The criteria’s overriding focus on assessing the scale, diversity and integration of hydrocarbons appears to be increasingly unfit when taking a long-term view. The methodological approach for business profiles should explicitly consider meaningful contributions from low-carbon activities – businesses that normally fall outside the oil and gas sector remit.