Conflating Queensland's coking and thermal coal industries

Download Full Report

Key Findings

Coking coal is valued at three times the price of thermal coal.

Thermal coal is used to generate electricity and is rapidly approaching technological obsolesce.

Executive Summary

Coking coal (also known as metallurgical coal) is used for steel manufacturing. Thermal coal is used to generate electricity.

Coking coal and thermal coal are two completely different products of vastly different value to Queensland, supplying entirely different industries and with very different volume trajectories going forward.

According to IEEFA estimates for the calendar year of 2018 for Queensland coal exports:

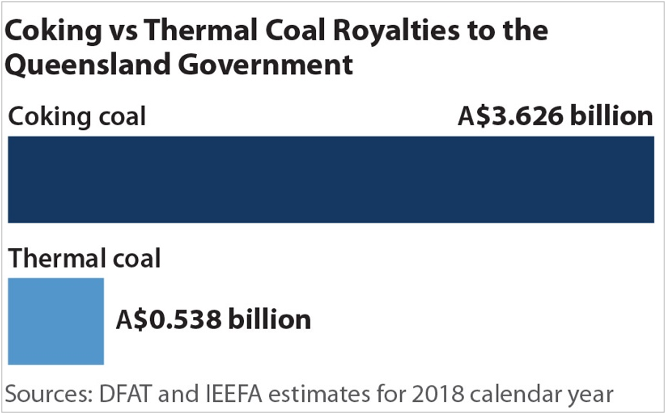

- Coking coal royalties are seven times more than thermal coal royalties in the Queensland budget, estimated at $3,626m versus just $538m from export thermal coal.

- Coking coal contributes an overwhelming 87% of the coal royalties to the Queensland government. Standalone thermal coal mines generate less than 10% of Queensland coal royalties.

- Coking coal royalties averaged at $23/tonne for coking coal vs. just A$8/tonne for thermal coal.

- Coking coal contributes 71% of total Queensland export coal volumes, but a much more significant 82% of the value of coal exports.

Given a progressive royalty rate for higher value products, coking coal export royalties reach 15% of value (in-excess of A$150/t), whereas thermal coal export royalties are predominantly charged a 7% royalty rate. In calendar year 2018, thermal coal export royalties averaged just A$8/t vs. $23/t for coking coal.

Coking coal is valued at three times the price of thermal coal.

Coking coal is used for steel manufacturing and is far from technologically obsolete. But there are alternatives to coking coal in supplying steel. One quarter of steel is made with scrap and electric arc furnaces, and at some point, if the world is to achieve the Paris Agreement, coking coal emissions will need to be addressed.

Coking coal is valued at three times the price of thermal coal, far more able to carry the internalised cost of carbon emissions and is significantly less challenged by lower cost technology innovations.

Thermal coal is used to generate electricity and is rapidly approaching technological obsolesce.

As a result, new thermal coal basins are un-bankable and of marginal viability.

Stranded asset risks for thermal coal, the associated supporting infrastructure investments and coal-fired power plants are rising. The urgency of dealing with the climate crisis is increasingly clear to financial institutions and financial regulators.

To date, 112 globally significant financial institutions have introduced thermal coal policy restrictions.

Adani has found it impossible to secure financial backers for its Carmichael thermal coal mine proposal in Queensland’s Galilee Basin.

Given a three-year construction timeline and the proposed 7-year royalty holiday gifted by the Queensland government, the often-touted benefit of additional royalties from the Carmichael thermal coal mine proposal ignores that zero royalties are likely to be paid in the coming decade.

Queensland Treasury forecasts point to speeding and red-light camera penalties being likely to contribute more to the Queensland budget than thermal coal in the next few years.

A tonne of coking coal in Queensland pays four times the export royalties and is worth three times as much as low energy, high ash Carmichael thermal coal.

Queensland is the world leading supplier of coking coal for steel manufacture.

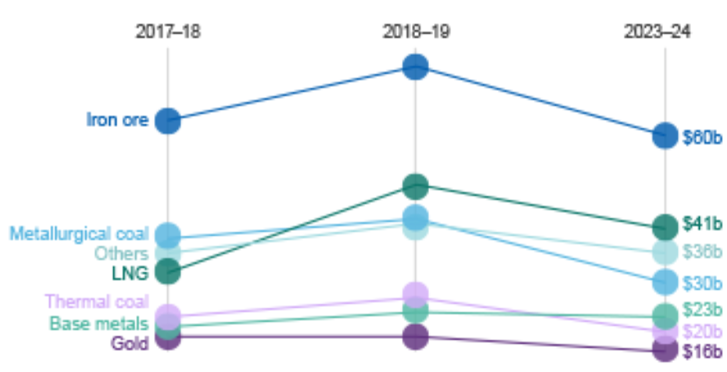

And coking coal, iron ore, and liquid natural gas (LNG) are Australia’s three top mining and energy exports, rivalling tourism and education in their export value to Australia, highlighted by the Office of the Chief Economist (Figure 1).

In contrast, thermal coal use peaked globally back in 2014 and is set for terminal decline by 2050 if we are to limit global warming below dangerous levels (+1.5-2°C). The costs to Australia of extreme weather events and climate inaction are already A$19bn annually and set to double.

Conflating coking coal with structurally challenged thermal coal tarnishes the overall resource sector’s social licence to operate. Global mining houses are being tarred defending the indefensible.

Forward looking mining houses like Rio Tinto planned their exit from thermal coal long ago. Andrew Forrest’s Fortescue Metals have ruled out entering the thermal coal mining sector in favour of investing in value-added opportunities in mining and new energy industries of the future, like hydrogen and lithium. BHP has now drawn the distinction with their no new thermal coal investments position.

Queensland needs to be strategic and develop those resources that have the highest value to the State.

For IEEFA, the first step for Queensland would be a ‘no new thermal coal mine’ policy, highlighting the distinctly differing outlook of higher value-added coking coal for steel manufacturing vs. thermal coal. This would allow a sensible, bi-partisan debate and buy Queensland’s industry, community and workforce the time needed for an orderly transition over the coming decade.

The first step for Queensland would be a ‘no new thermal coal mine’ policy.

A ‘no new thermal coal mines’ policy would materially reduce the stigma and associated blame being felt by the state’s world-leading coking coal export sector, differentiating coking coal from the terminal decline prospects facing the thermal coal sector.

Expanding the extraction and use of thermal coal undermines the Paris Agreement, and is a policy objective of zero relevance to the outlook for Queensland’s coking coal, LNG or mining activities in rare earths, lithium and cobalt, all critical components of the supply chain for zero emissions industries of the future.

Figure 1: Australia’s Top Resource and Energy Exports 2018-19 (A$bn)

Source: Australian Government’s Office of the Chief Economist, March 2019.