Key Findings

Uganda’s elevated public debt levels threaten the macroeconomic stability needed to implement its fourth National Development Plan.

Uganda’s proposed USD1.8 billion oil refinery investment could pose significant risks to public finances.

Sustained, multi-year investment in climate-resilient, electrified industrialization offers a lower risk, lower cost approach to growing incomes and creating jobs.

Executive Summary

Uganda has increasingly limited room for fiscal maneuver as public debt rises and the global low carbon transition in oil markets accelerates. In January 2025, Uganda’s Parliament approved the country’s fourth National Development Plan (NDP IV), which aims to drive “higher household incomes, full monetization of the economy, and employment for sustainable socio-economic transformation” through to 2030. The Plan prioritizes industrialization — or capturing a higher proportion of chosen value chains — (in agriculture, minerals, oil and gas and tourism) as the primary approach to improving the quality of Ugandan lives, building on the achievements over the past two NDP periods, including reduced poverty levels, improved life expectancy and wider access to basic services.

NDP IV industrialization goals are also dependent on building stronger economic foundations across energy, transport, digitalization, and financial services. However, key macroeconomic indicators have shown weakening trends since 2022. According to recent figures, the country’s public debt to GDP has risen above 50%, indicating an elevated risk of potential debt distress. This, plus the declining availability of concessional financing, has meant that the share of public revenues allocated to debt interest has doubled to more than 30%, reducing fiscal space for essential areas of spending, such as health and education.

International rating agencies Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch Ratings downgraded the country’s sovereign credit ratings in 2024, and Ugandan officials have confirmed talks with the International Monetary Fund about a new Extended Credit Facility, which they aim to formalize in 2026.

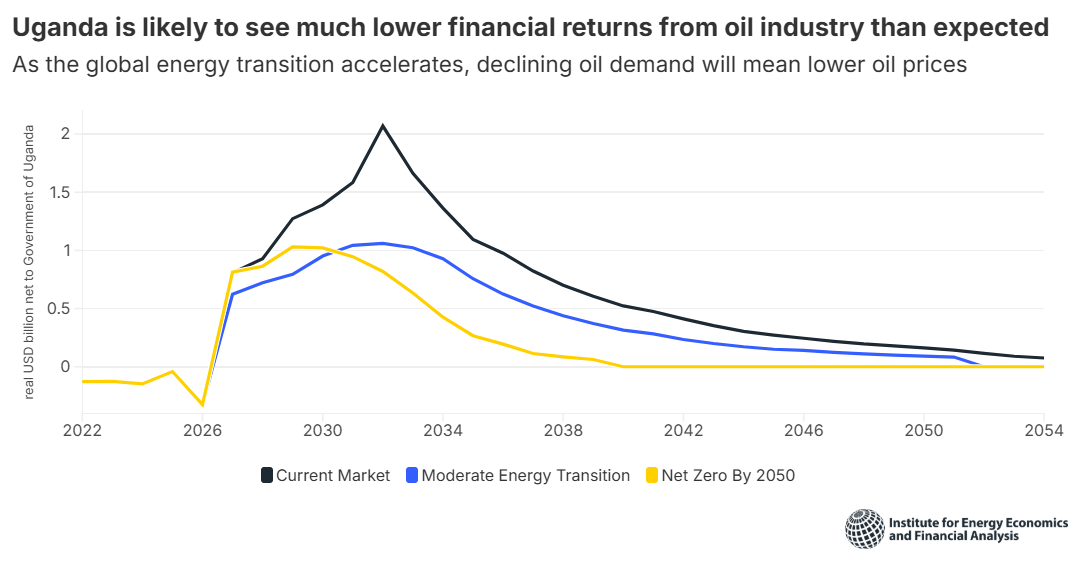

For years, markets and donors have expected the beginning of oil production to provide imminent succor to Uganda’s weakening public finances. However, as underscored in the companion paper to this report (Reassessing oil in Uganda: How do investments in Uganda’s oil industry stand up in an accelerating global transition), the development of Uganda’s oil industry has been beset by delays, cost overruns and financing challenges. We estimate Uganda could have invested more than USD2 billion by the time it begins to receive significant revenues from the sale of oil (most likely in the second half of 2026), including USD675 million in the controversial 1,443 kilometer East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) to the Indian Ocean at Tanga, Tanzania. With the accelerating global transition dampening the long-term outlook for Uganda’s share of oil revenues, the industry seems unlikely to be a major contributor to Uganda’s economic transformation.

Despite weakening public finances and uncertainties around the oil sector, Uganda appears set to double down on its bet on oil by building a USD4.5 billion oil refinery at the Kabaale Industrial Park in Hoima District. For a 40% share in the refinery (owned by state enterprise Uganda National Oil Company or UNOC), Uganda may commit an additional USD1.8 billion, assuming the project proceeds on time and within budget. To fund this and other projects, UNOC has agreed to borrow up to USD2 billion from commodity trader Vitol. Repayment of the Vitol loan will partially come from priority access to Uganda’s oil revenues deposited into an escrow account. This means that financing for the refinery will likely displace or defer the planned spending of these revenues on other public spending projects or investment for future generations.

This report examines how the changing context — including the impact of the global transition and the accelerating physical consequences of climate change — might change the calculus for Ugandan officials seeking to use an increasingly uncertain amount of future fiscal space to spur development through industrialization. In particular, the report explores the extent to which the risk-reward assessment in relation to the oil refinery has been shifted due to Uganda’s fiscal position.

The analysis identified four key findings:

Finding 1: Uganda’s elevated public debt threatens the macroeconomic stability needed to make its fourth National Development Plan a reality

Uganda’s NDP IV charts the substantial progress the country has made across its first three National Development Plans (since 2010) and more broadly, since independence from colonial rule. An important part of this has been macroeconomic stability. The Plan recognizes the importance of maintaining that stability to 2030 as the country attempts to drive a substantial increase in investment to drive industrialization. An economically weaker Uganda would — all else being equal — find it harder to attract non-concessional capital, and would pay a higher price to service whatever it could attract. This would impact its ability to achieve development objectives, not to mention the ability to achieve them in a “just” fashion that equitably allocates the costs and benefits of that development.

Despite the emphasis on macroeconomic stability, Uganda’s public finances have weakened, creating challenges for the Plan’s implementation. A significant part of these dynamics relates to factors outside Uganda’s control: the rise in US interest rates since 2022; elevated global energy prices since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in the same year; and more recent dynamics that have limited the ability and willingness of traditional development partners to provide funds at concessional rates.

However, the decision to proceed with developing the Ugandan oil industry has also played a role in weakening public finances. Construction has temporarily raised public debt, due to the country’s equity contribution to the EACOP pipeline. Delays in construction have meant that the revenues required to service new borrowing have yet to flow. These, and other factors have tripled the amount Uganda would have expected to invest during this phase, further increasing public borrowing.

For a country with stronger economic foundations and more financial flexibility, the risks discussed in the Reassessing oil in Uganda paper may be inconvenient but manageable without significant collateral damage to the economy. Higher investment in one area could be offset by reduced spending elsewhere, or the country might make the case to credit rating agencies and sovereign bond investors/lenders to look at the country’s underlying economic trajectory even if oil revenues are slightly delayed. However, for Uganda, oil-related economic risks — given their magnitude relative to the size of the economy and the country’s limited financial flexibility — could contribute to declining credit ratings and rising cost of capital.

This is the context in which Uganda will face emerging economic and geopolitical challenges of the day, as well as the accelerating physical consequences of climate change. Uganda is particularly vulnerable to the latter, evident through increasingly unpredictable rainfall patterns and heat stress. These factors, combined with limited economic resilience, will shape the implementation of the NDP IV. Ugandan officials will need to consider a range of potential pathways to achieve development objectives and support sustainable wealth and job creation.

Finding 2: Uganda’s proposed USD1.8 billion refinery investment could pose significant risks to public finances.

Large investments like the EACOP, the Tilenga and Kingfisher oil fields and the proposed oil refinery are often the riskiest for economies like Uganda because they have limited economic flexibility to manage the timing difference between investment outlay and revenues. They are often pursued because they also offer the promise of large development gains if implemented well. However, the country’s limited experience with complex construction projects, infrastructure gaps and the apparent unavailability of project finance debt increase risks for Uganda as an anchor investor in the project. The decision to turn to a resource-backed loan to fund the equity stake could further increase complexity; delay any oil-related development benefits; and erode some of the agency over its energy future that Uganda ostensibly hoped to gain through the investment in the first place.

The proposed oil refinery may have been less controversial than the EACOP pipeline project, but it arguably poses a greater risk to Uganda’s public finances during construction. Uganda’s share of investment is 40% compared with 15% for EACOP. The decision to finance the USD4.5 billion project entirely through equity (as opposed to the original plan to use up to 60% project finance debt) is expected to triple Uganda’s contribution to the investment to about USD1.8 billion, nearly three times its contribution to the EACOP pipeline.

In December 2025, the Ugandan Parliament granted consent for UNOC to sign a 7-year loan facility of up to USD2 billion with commodity trader Vitol that would fund projects including part of Uganda’s equity commitment in the refinery. The facility has a lower headline interest rate than Uganda’s current cost of non-commercial borrowing. However, this benefit appears to come with significant costs. The loan has a floating rate, meaning that the deal will increase Uganda’s short-term exposure to volatility in international financial markets. Vitol would have priority access to Ugandan crude oil export revenues as a source of funds for repayment, meaning that oil-related development spending could be delayed if construction of the refinery is delayed or if operational issues mean that the refinery yields less than expected. Finally, the deal appears to cede some control over Uganda’s energy future to a player that is already the dominant supplier of liquid fuels to the country, and which is not incentivized to minimize costs to the Ugandan economy.

Uganda will also retain exposure to construction and climate transition risks. Our analysis shows that a construction cost overrun of 25% (compared with an expected overrun of over 50% on the EACOP project) would push the refinery project’s internal rate of return (IRR) down to 10%. In that case, the project’s financial return would be lower than the minimum most financial investors would demand for an investment of this type and would barely be enough to cover Uganda’s cost of non-concessional borrowing. Given the recent history of cost overruns in oil refinery projects (the Dangote refinery in Nigeria is reported to have ended up costing more than twice the original estimate), this means there is a high chance the project, by itself, will not make any money.

Our analysis also factored in the climate transition risk the refinery might face in a world with an accelerated decarbonization profile. Using the “moderate” and “Net Zero Emissions (NZE)” transition scenarios from the Reassessing oil in Uganda paper, we assessed how lower long-run global oil prices, weaker refining margins, and the declining competitiveness of Ugandan oil production by the end of the 2030s (in the NZE scenario) would affect the refinery. If the refinery is delivered on time and on budget, a moderate transition scenario would have the same impact as a 25% cost overrun (i.e. reducing the IRR to around 10%), while under the NZE scenario, the refinery’s IRR would be closer to 5%. The combination of a moderate transition scenario and a 25% capital cost overrun would push the IRR down to about 8%, lower than Uganda’s cost of borrowing in international markets.

On top of these risks, the tolling agreement UNOC is reportedly negotiating with Emirati partner Alpha MBM Investments could further weaken Uganda’s position in an accelerated global transition by transferring oil-price risk to the country. This agreement, if signed, could compound the impact of the potential oil production sharing contract renegotiation reviewed in the Reassessing oil in Uganda paper. Both agreements would insulate Uganda’s partners against the impacts of an accelerated global transition, at Uganda’s expense.

Since Uganda has limited power to manage these risks, and limited capacity to absorb potential losses, the authors ask whether there might be a less risky way to allocate the money earmarked for the refinery investment. What are the country’s options if it were to delay or cancel the planned refinery?

Finding 3: Sustained, multi-year investment in climate-resilient, electrified industrialization would be a less risky, lower-cost approach to growing incomes and creating jobs

Delaying or cancelling the refinery could free up fiscal space for other investments in industrialization that would advance Uganda’s NDP IV goals, but with considerably lower risk to public finances.

An alternative strategy would focus on a higher number of smaller, less complex construction projects in sectors with less exposure to the global transition. A more diversified portfolio of investments would reduce implementation risks associated with any single project and, through shorter construction periods spread across the country, could bring economic benefits to more Ugandans, earlier. We reviewed Uganda’s existing strategy documents and secondary literature to outline alternative potential strategies that could deliver many of the same economic benefits as those expected from the refinery. High-priority projects should deliver high economic multiplier effects, contribute to an improvement in the trade balance, and attract additional sources of concessional finance.

We found strong arguments for accelerating investment to enable greater industrialization of agriculture, which contributes more than 60% of Uganda’s jobs and most rural jobs. Increasing value addition and climate resilience in agriculture will also be critical if Uganda is to achieve one of the key NDP IV objectives, namely, moving 30% of the population engaged in subsistence agriculture into the money economy. Previous efforts to enable agricultural transformation have had limited success, with substantially lower returns from rural electricity access programs compared with those in urban areas, and with limited penetration of clean cooking technologies. In parallel, investments in electricity generation capacity have pushed contingent liabilities onto the national government as demand has not risen fast enough to absorb increased supply.

An alternative strategy could be to increase supply and demand for modern energy services in tandem. This could mean prioritizing faster-to-deploy technologies (including off-grid and mini-grid solutions) and support for manufacturing activities that are job-rich. This could create reliable demand on the power system that can support future investment in transmission and distribution networks and, in turn, in further generation capacity. Investment programs designed to account for the physical risks of climate change while maximizing social co-benefits for Ugandans are most likely to achieve sustainable growth in wealth and jobs. An alternative strategy of the sort discussed in this paper might also be more likely to meet the goals of the new Uganda Just Transition Framework.

The sequencing and distribution of Ugandan development investments will become an increasingly important consideration as Uganda pursues greater integration in regional trade networks (for example, within the East African Community or under the African Continental Free Trade Agreement). High-quality businesses may experience accelerated growth through exports, but as logistics and transport connections increase, the risk of import substitution will also rise.

To be competitive in external markets — and to reduce the cost of goods and services in the country — Uganda should prioritize efforts to improve the efficiency of, and reduce the cost of, key infrastructure, including energy, transport, logistics, and digital and financial services. If this is done without locking Uganda into a particular technological pathway/economic paradigm (for example, in relation to oil), it will allow the country to benefit from low-carbon industrial innovation being pursued across the world. An alternative approach that puts less pressure on public finances could be a more effective way of reducing Uganda’s dependence on foreign powers than an oil refinery investment that trades external energy dependence for capital dependence.

New analytics — including those presented here and in the Reassessing oil in Uganda paper — make it possible to assess the economic risks associated with climate change or the global transition. Ugandan officials have access to climate risk scenarios and international technical exchange through membership of fora such as the Network for Greening the Financial System (Bank of Uganda is a member) and the Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action (the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development is co-chair).

However, even the most sophisticated normative climate scenarios cannot capture the increasing uncertainty of a world with fast-changing trade patterns and the potentially massive impact of artificial intelligence. Uganda may have a higher chance of achieving its development objectives if it can incorporate a more in-depth understanding of global changes and their economic implications into its planning process, instead of relying on long-term ambitions and relatively static assumptions.

To make the best use of limited fiscal space, Ugandan officials could benefit from treating risk management as a continuous process, incorporating the best available intelligence on internal and external hazards. It should be embedded in an institutional framework that ensures this intelligence is consistently fed into policymaking. Within such a framework, concentrating scarce public resources in the oil refinery presents high downside risk compared to a diversified, climate-resilient industrialization strategy. The country may be best placed to achieve the goals under NDP IV if it spreads its bets and avoids further investment in oil.