India: Why ESG strategies are fast becoming a mainstay in corporate financial planning

Over recent years evidence has been mounting that for corporations, numerous benefits accrue from presenting an attractive profile on environmental, social and governance (ESG) policies and adopting more sustainable business practices. These material benefits reflect in the bottom line of the company in one way or another.

Capitalise on a growing pool of ESG-aligned capital

As reflected in Part 1 of this series, investors managing assets upwards of $120 trillion have pledged to consider ESG aspects in their investment decision-making. Demand for ESG-aligned instruments has grown in recent months. Instruments such as green bonds, sustainability-linked bonds, social bonds and transition bonds are being increasingly issued by companies, sovereigns and municipalities.

Globally, issuance of sustainable finance bonds totalled $1 trillion in 2021 – green bonds, the most widely used instrument in the space, accounted for $488 billion, an all-time high. Further, sustainable loans totalled $717 billion for the year, more than tripling the levels of the previous year, another calendar year record. Bloomberg expects ESG assets to hit $53 trillion by 2025, a third of global assets under management.

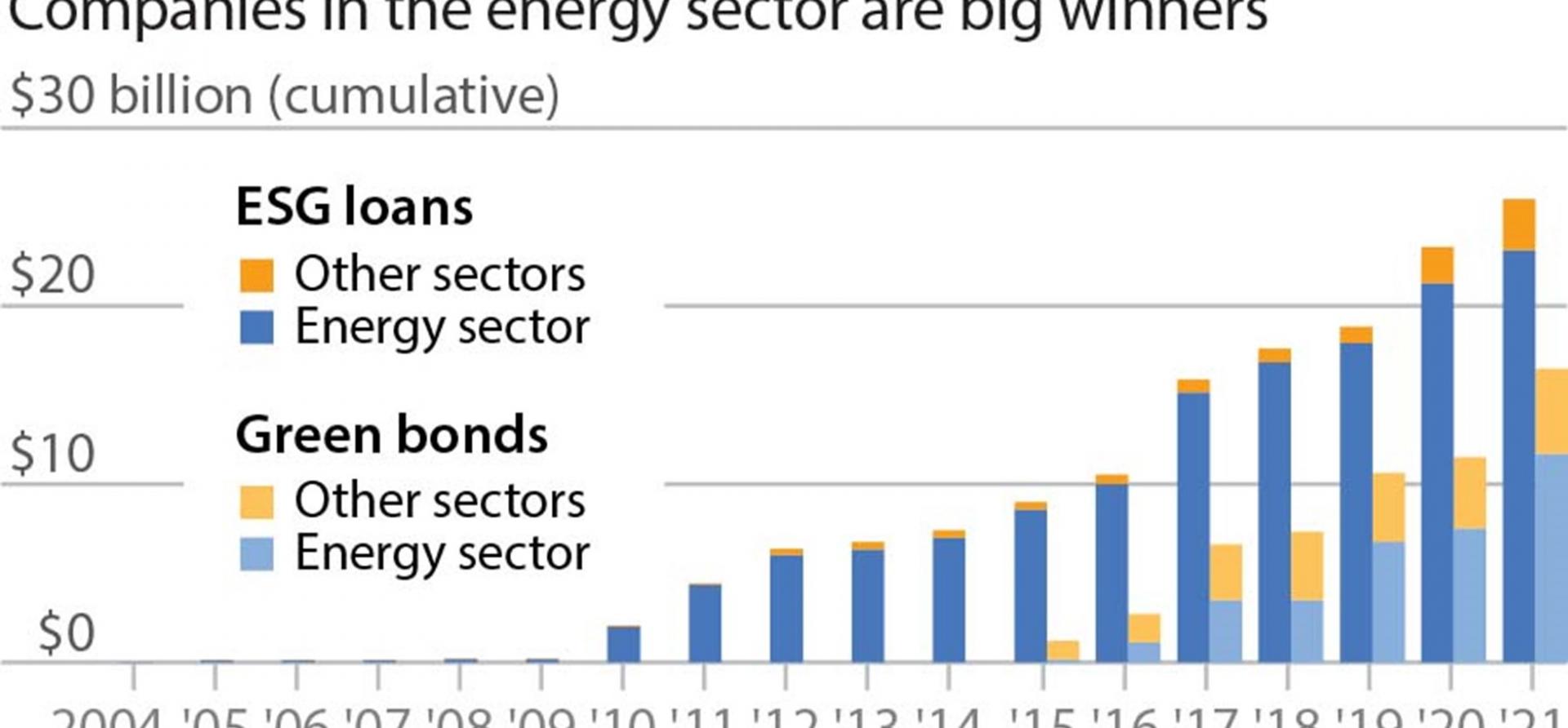

In India, green bond issuances have increased primarily via energy sector companies. Indian firms have raised US$16.7 billion worth of green bonds, US$26.1 billion of ESG loans and US$3.1 billion of other ESG bonds since the start of 2010s. Still, this is low compared to global issuances of ESG-aligned bonds and loans.

Entities that highlight efforts towards improving their ESG profile and presenting ESG-qualified assets will find it easier to tap into this growing pool of global capital.

Table 1: Share Price Performance of Energy Sector Companies

Positive Reinforcement of a Company’s Share Price

A study by Harvard Business School found that over a 20-year period, firms that did well on material sustainability factors outperformed those that did poorly, on both stock returns and corporate profits. In India, three sustainability indices of Bombay Stock Exchange (S&P BSE Carbonex, S&P BSE Greenex and S&P BSE 100 ESG index) have outperformed the Sensex during the pandemic.

Table 2: Share Price Performance of Energy Sector Companies

The above table shows the share price performance of four energy sector companies over the past five years. Orsted of Denmark, one of the world’s largest clean energy companies, has given astronomical returns as it pivoted towards green energy. Similarly in India, Tata Power, a conventional utility, shared plans to have entirely renewable-led growth, which resulted in its share price shooting up massively in the past two years. On the other hand, Royal Dutch Shell and Coal India Limited failed to present credible strategies or efforts to shed their fossil fuel-heavy image, which contributed to their share prices plunging.

Rising Pressure from Supply Chain Partners

Corporations globally have been pledging to lower emissions. However, according to a Standard Chartered study of 400 MNCs, rather than focussing on their own carbon output, more than two-thirds of multinationals plan to first tackle their supply chains’ emissions.

Increasingly, organisations are pledging to reduce Scope 3 emissions generated in the entire value chain – beginning with sourcing the raw materials and continuing through manufacturing, transporting and use of the end product. For the energy sector, Scope 3 emissions are an even more important consideration as they include emissions released by the use of their end products, such as combustion of coal in thermal power plants. As per IHS Markit, Scope 3 emissions in 2019 accounted for an average of 75% of total GHG emissions from the electric utility sector, and about 88% from the oil and gas sector.

Companies will prefer to do business with supply chain partners who disclose their carbon footprints and make credible efforts to reduce them.

Regulatory Environment Transforming to Reward ESG Disclosures

The regulatory environment is also evolving to reward companies with more comprehensive ESG disclosures while tightening the noose around those not complying. In May 2021, a court in the Netherlands ruled in a landmark case that the oil giant Shell must cut its CO2 emissions by 45% compared to 2019 levels, the first time a company has been legally obliged to align its policies with the Paris climate accords.

Green taxonomies, now rolling out worldwide, are another reason for companies to start measuring and disclosing their ESG footprint. Taxonomy is a classification system, establishing a list of environmentally sustainable economic activities. An ESG strategy that includes ascertaining the ESG footprint of an organisation’s economic activities will help investors and financiers map these activities with individual country taxonomies and channel capital towards them.

In India, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) has mandated that ESG mutual funds invest only in companies disclosing their ESG footprint as per the new business responsibility and sustainability reporting (BRSR) standards.

Reputational Benefits and Brand Building

As consumers become more aware of their carbon footprint. an enhanced ESG profile leads to building a stronger reputation among them. ESG reporting gives tangible data to the intangible asset that is a company’s brand. It also allows companies to align themselves publicly with values that affect brand perception. Increasingly, employees are also looking beyond remuneration while assessing their current or potential employers.

Reputational damages due to an adverse environmental footprint can lead to protests, customer boycotts, lawsuits and dearth of capital. In 2017, the four biggest Australian banks distanced themselves from the Adani Group’s Queensland coal project following the negative publicity that it garnered.

Lower Cost of Capital for Capital Expenditure

In developed and emerging markets alike, according to a study by MSCI, companies with high ESG scores, on average, experienced lower costs of capital compared to companies with poor ESG scores. Similarly, McKinsey cites several studies that point to higher ESG scores translating to almost 10% lower cost of capital for companies.

Among the reasons is that companies with a high ESG score tend to have lower regulatory, environmental and litigation risks, so investors build in lower risk premiums when investing in them. Given the increasing demand among investors for ESG debt instruments, their pricing has been more favourable for issuers compared to plain vanilla instruments.

Investors vie for renewable energy assets, lowering their cost of capital. Globally, they are putting pressure on banks to reduce or eliminate fossil-fuel financing and increase lending to cleaner technologies. Bank of America (BoA), JBIC of Japan, HSBC, Barclays and Deutsche Bank are among major global financial institutions growing their sustainable books.

Cost of Capital for Various Energy Sector Assets

Source: Bloomberg

Significance of ESG Standards and Ratings

A major inhibiting factor when tapping the ESG pool of capital is lack of sustainability disclosures or absence of ways that make it easier for stakeholders to understand a company’s ESG standing.

Sustainability standards and frameworks help companies overcome this barrier by becoming the basis for how companies set KPIs, what they measure, and what information goes in the sustainability reports they create.

There are growing regulatory mandates for businesses to report on their ESG metrics, but several voluntary frameworks and standards are also available. Globally, investors are familiar with these, so a company aligned with the top voluntary ESG standards will have easier access to the ESG capital pool.

There are growing regulatory mandates for businesses to report on their ESG metrics

The most widely used ESG reporting standards are Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and The Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). IIRC and SASB consolidated their businesses in June 2021, to form the Value Reporting Foundation.

With ESG standards, a company’s sustainability efforts can be correctly determined by all stakeholders, and not by untested claims of a green persona.

Another important facet in the ESG process is the rating or score from third-party providers, which measure a company’s exposure to long-term ESG risks. Key issues are identified for each industry and weighted according to their timeline and potential impact.

Credit rating agencies such as S&P, Moody’s and Fitch, along with companies such as Bloomberg, MSCI and Refinitiv, provide ESG scores for companies. A higher score can be a significant factor in attracting ESG capital.

In India, CRISIL recently launched ESG scoring of 225 listed companies. Edelweiss also launched an ESG scorecard and ratings for India’s top 100 companies (aligned to NSE 100).

ESG ratings will gain importance in coming years, given increasing investor pressure and greater legislative and regulatory focus on integrating ESG factors by financial market participants in investment decision-making. Companies that imbibe a culture of considering ESG in all decision-making will earn superior ratings.

This article first appeared in Carbon Copy. Read Part 1 and Part 3.

Shantanu Srivastava is an energy finance analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA)