IEEFA: Reducing land-use impacts of renewable generation could smooth the path for India’s energy transition

6 September 2021 (IEEFA India): Judicious planning of land use for solar and wind generation will help India to achieve its renewable energy ambitions, according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis’ (IEEFA) new report which examines how much land would be needed for the country to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

IEEFA has calculated that if India were to implement a mid-century net-zero target, solar could occupy in the range of 50,000-75,000 square kilometres (km2) of land, while wind could use a further 1,500-2,000 km2 (for the land area directly impacted by turbine pads, sub-stations, roads and buildings) or 15,000-20,000 km2 (the total project area including space between turbines and other infrastructure).

Planning of land use for solar and wind generation will help India to achieve its renewable energy ambitions

The amount of land that could be needed for solar is equivalent to 1.7-2.5% of India’s total landmass, or 2.2-3.3% of non-forested land.

The report’s author Dr Charles Worringham, researcher and IEEFA guest contributor, explains that the higher end of the land-use range is deliberately generous to allow plenty of leeway for planning.

“This is a precautionary approach for the purposes of planning and putting in place smart land-use policies today for future renewable infrastructure,” he says.

Comparing the effects of large-scale renewable expansion to those of meeting electricity requirements from additional coal-fired power, Worringham noted that the locations for renewable energy generation can be chosen using India’s preferred social and environmental criteria and can be widely distributed across the country.

“Additional coal can only come from already heavily mined districts or from new coal blocks, which are often in significant forest areas and where displacement of Adivasi communities is an issue.

“Nor does renewable energy permanently alter land and natural resources in the same way as coal.”

The report notes the potential for land-use conflict to arise over renewable energy installations, even in sparsely populated areas, slowing the rollout of infrastructure.

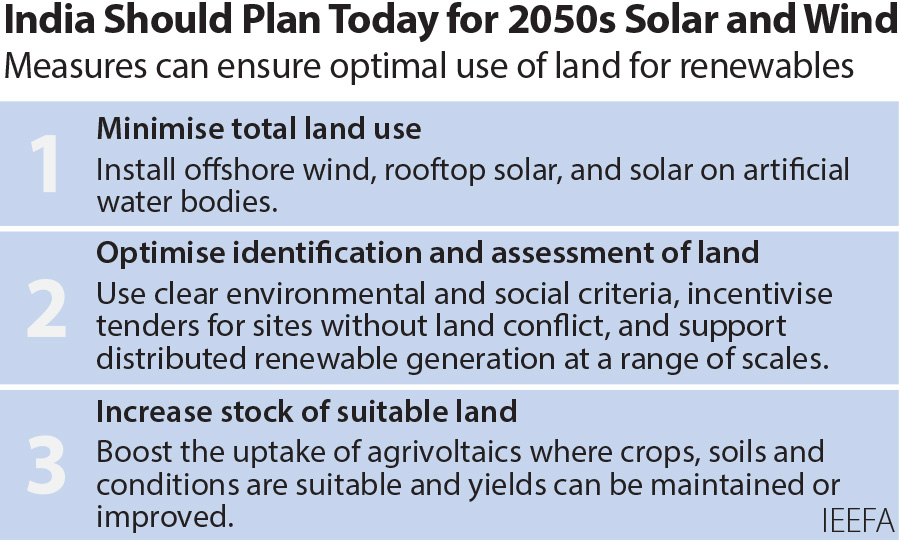

Beyond reinforcing the need to accelerate energy efficiency gains and reduced grid transmission losses to reduce the total growth in demand, the report discusses how to maximise the benefits and minimise the costs of land use for the energy transition and makes recommendations in three categories:

- Minimising total land-use requirements through offshore wind, distributed rooftop solar, and solar on artificial water bodies.

- Optimising the identification and assessment of land. Measures include developing clear environmental and social criteria for rating potential sites; undertaking comprehensive independent assessments of potential sites against these criteria in advance of tenders or project proposals; incentivising the selection of tenders on sites where there is no land conflict; limiting concentration of generation in single regions and supporting widely distributed renewable generation at a range of scales.

- Increasing the stock of potentially suitable geographically diverse lands by boosting the uptake of agrivoltaics where crops, soils and conditions are suitable and yields can be maintained or improved.

Agricultural land has the potential to host a much larger proportion of renewable generation, providing a boost to the rural economy and reducing pressure on other land, according to the report.

Nurturing an Indian agrivoltaics sector could provide benefits to farmers such as a second income stream, says Worringham.

“Whether or not India commits to a mid-century net-zero emissions target, its huge expansion of renewable energy capacity over the coming decades will enhance energy security enormously, but this requires a large amount of land for infrastructure,” he says.

“The energy transition will also require important choices about where this infrastructure should be located. But careful planning and solutions like agrivoltaics, distributed energy systems and offshore wind can also greatly reduce the potential for renewable generation to conflict with social and environmental values whilst diversifying and strengthening India’s national grid. By bringing more generation closer to both urban and rural loads, transmission costs could also be kept in check.”

Read the report: Renewable Energy and Land Use in India by Mid-Century

Media contact: Rosamond Hutt ([email protected]) +61 406 676 318

Author contact: Dr Charles Worringham ([email protected])

About IEEFA: The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) examines issues related to energy markets, trends and policies. The Institute’s mission is to accelerate the transition to a diverse, sustainable and profitable energy economy. www.ieefa.org