Key Findings

Uganda’s oil industry is delayed, over budget and likely to disappoint when it comes to returns.

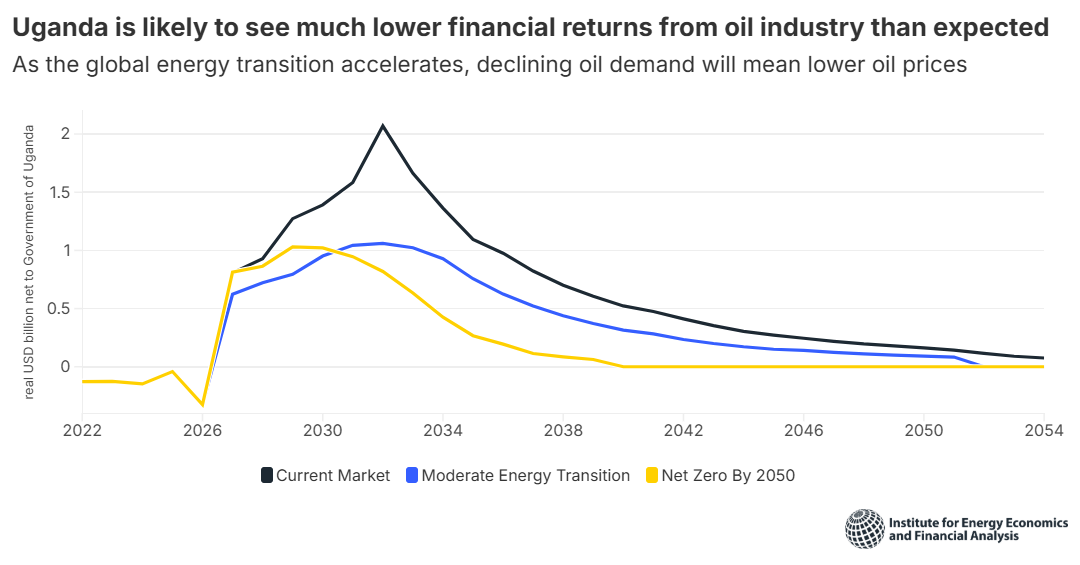

Accelerated global decarbonization could mean the value of Uganda’s oil falls as much as 34% for foreign investors and 53% for the country.

Investments in oil are unlikely to be a transformative driver of Ugandan development and could add significant risks to public finances.

Executive Summary

Three-and-a-half years after TotalEnergies, China National Offshore Oil Company, the Uganda National Oil Company, and the Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation announced a final investment decision (FID) for the first phase of Uganda’s new oil industry, construction is reportedly more than halfway complete, with more than USD6 billion already invested at the end of 2024.

The project includes development of more than 1 billion barrels of oil at the six Tilenga oil fields, operated by TotalEnergies, and the Kingfisher field, operated by the China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC), as well as the construction of the 1,443-kilometer East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), which routes through Tanzania to the port of Tanga for oil export.

Oil has long been touted for its transformative potential on Uganda’s economy, bringing a short-term boom in foreign direct investment, significant new government revenues, and trade balance benefits that could be amplified by a planned refinery project. However, project delays, cost overruns, and changes in global oil and energy markets since the FID mean that the project is likely to be a disappointment for investors and the Ugandan economy.

Questions have also been raised about the project’s economic viability, given the accelerating global action on decarbonization. A 2020 analysis by non-profit Climate Policy Initiative’s Energy Finance (CPI EF) team found that delays had eroded 70% of the Ugandan oil industry’s potential value and identified significant economic and financial hurdles to overcome before an economically viable proposition could be reached. This report provides an updated position on the issues addressed in the CPI EF 2020 report:

- Does it (still) make sense to proceed to oil production?

- What economic, financial and policy options do each of the key parties have?

- How might geopolitical volatility and a world grappling with intensifying climate change and an increasingly “disorderly” transition influence the value of those options?

The analysis identified three key findings:

Finding 1: Uganda’s oil industry is delayed, over budget and its results are likely to fall well short of expectations.

At the time of FID, oil production was slated to start in 2025, but first oil now appears to have slipped until late 2026 or 2027. The project’s total construction cost is expected to be significantly higher than the initial budget, particularly for the EACOP. Recent public estimates put EACOP’s likely cost at around USD5.6 billion, a 55% increase from the USD3.6 billion projected shortly before FID.

Over the same period, oil markets and the global economy have also gone through a period of significant volatility and structural change that has contributed to a lower long-term outlook for global oil prices than when the FID was made.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine threw global energy markets into turmoil. Prices of major energy commodities and products spiked significantly in 2022. Sanctions and the responses to sanctions have dramatically altered the shape of the global energy trade. Russia exports almost 15% less oil today than it did in 2022, but the impact of reduced Russian supply has been outweighed by continuing growth in U.S. production; growth in areas such as Brazil and Guyana; and the unwinding of COVID-19-era output cuts from the OPEC+ consortium. This, combined with a weakened demand outlook caused by the impact of U.S. tariffs on global economic growth and plateauing demand in China caused by the rapid growth of electric vehicles, means the expected future oil price trajectory today is significantly below the trajectory at the time of the FID.

On top of construction delays, cost overruns and lower-than-expected oil prices that have all contributed to weakening project economics, the apparent difficulties in securing debt financing for EACOP will push returns down even more since shareholders will need to invest more in the short term than they had planned at FID.

Even in today’s markets, TotalEnergies and CNOOC appear to achieve only modest returns above their weighted average cost of capital (WACC) and significantly less than typical targeted rates of return for the sector. Ugandan government revenues are also likely to be significantly less than expected.

Finding 2: Accelerated global decarbonization could mean the value of Uganda’s oil falls as much as 34% for foreign investors and 53% for Uganda.

Although policy support for a global transition has been rolled back in some areas, the growth in uptake of electric vehicles, driven by China, continues to surpass analyst predictions. Future oil demand and prices may be significantly lower than the market currently expects, and lower prices would reduce Ugandan oil industry returns even more.

We modelled the impact of two global transition scenarios (the “moderate” transition scenario and the even faster “Net Zero Emissions (NZE)” scenario) on the cash flows of Uganda’s oil fields and EACOP. In these scenarios, foreign private investments in Uganda’s oil industry could end up being value-destructive (i.e. deliver a financial return lower than the companies’ WACC over the life of the industry). However, expected returns on a point-forward basis (i.e., based on cash flows from 2025 onwards), would still be positive even in the global transition scenarios. TotalEnergies’ stake, worth around 3% of its market capitalization in November 2025, would be worth 25% less in our moderate transition scenario and 34% less in the NZE scenario.

The uncertainty around which accelerated transition path is most likely to prevail highlights the increasing challenge that Uganda will face when predicting the future contribution of oil revenues to the economy and public budget. However, regardless of the scenario, Uganda risks losing a higher proportion of its returns than the foreign oil companies. Our analysis shows the present value of Uganda’s future revenues being 37% lower in the moderate transition scenario and 53% in the NZE scenario.

Uganda is more exposed to “climate transition risk” than foreign investors because of the ways in which the investors have agreed to split risks and rewards. Most of the industry’s revenues accrue to foreign investors in the early years of production due to the agreement that allows those investors to recoup their investment costs, with Uganda standing to earn a growing share of oil industry profits over time. While this type of arrangement has historically been a typical approach to incentivizing foreign investors to put up the capital for the oil industry for developments, it leaves Uganda particularly exposed to the impacts of an accelerated global transition that it has little influence over.

Finding 3: Investments in oil are unlikely to be a transformative driver of Ugandan development and could add significant risks to public finances.

Since “commercially recoverable” quantities of oil were confirmed in Uganda in 2006, Ugandan officials have placed great store on the potential for the industry to spur economic transformation, including the public policy goal to reach upper middle-income status by 2040. The country envisioned an industry that would create tens of thousands of jobs, while domestic production liquid fuels and derivative products, such as petrochemicals and fertilizers, would reduce Uganda’s dependence on imports. Meanwhile, oil revenues would be used to increase investment in new infrastructure and to invest for future generations. However, Uganda’s weakening public finance position could severely limit the country’s ability to achieve these goals, especially given the risks explored in this paper.

Uganda’s sovereign credit rating was downgraded in 2024 by Moody’s to B3 and Fitch to B. At these weak sub-investment or speculative grade levels, the country could expect to face uncertain access to global capital markets, increasing its reliance on development partners. At the same time, the capacity of development partners is increasingly under pressure, especially as the U.S. seeks to reduce its contributions to multilateral institutions. The country’s apparent attempts to negotiate a new International Monetary Fund (IMF) facility highlights Uganda’s increasing liquidity challenges and the rising amount of GDP being allocated for debt service payments. Deteriorating public debt sustainability creates a situation in which significant further delays or increased costs could lead to further downgrades that exacerbate economic and financial stability pressures.

First oil would bring the prospect of revenues that could partially alleviate liquidity challenges. However, uncertainty around the amount of oil revenues because of climate transition risk means that relying on them to safeguard public debt sustainability is an increasingly risky gambit. Any net benefits to Uganda from oil appear more likely to provide a short-term budgetary cushion than to drive economic transformation.

Our analysis also considers how the potential oil-related economic benefits and risks around an accelerated transition would be distributed. Uganda has created rules that grant almost complete control to the national government on the spending of oil revenues and which explicitly seek to manage the impact of oil-price cyclicality on public spending. Under the rules, 0.8% of the previous year’s non-oil GDP can be allocated to the annual budget for “infrastructure and development” projects, with the remainder allocated to a long-term investment fund. In the base case, this means at least 30% of government oil revenues would be allocated to the fund. In our transition scenarios, however, the amount invested for future generations falls by up to 70%.

This implies that unless other oil projects are developed in Uganda, the windfall from the resources may be insufficient to capitalize an investment fund at a scale that would be transformational for the country. A faster global transition limits the potential for oil to drive sustainable improvement in development outcomes in Uganda. This position could further be eroded if Uganda pursues its current plans to build an oil refinery, as set out in our parallel paper Climate-resilient development in Uganda: How a global transition and fiscal constraints could influence Uganda’s development choices.”

Uganda’s published strategies for medium-term development show bold ambition to industrialize the country in a sustainable manner, creating a virtuous circle of higher employment rates, income levels and quality of life. At a time of challenging global financial market conditions, monetizing Uganda’s oil reserves may have seemed like a natural and even appropriate means for Uganda to take control of financing its development and reducing reliance on foreign donors.

If they were happening a decade ago, securing external financing for potential investments in Uganda’s oil industry would have been more straightforward. However, structural changes largely outside of Uganda’s control have made investments in the country’s oil much less lucrative than expected. In addition, the amount that Uganda has been expected to contribute before earning any significant revenues has tripled. The commitment of ever-higher levels of investment (that could be dwarfed by a further potential USD1.8 billion planned for the refinery) for lower-than-expected economic returns will erode the potential for oil revenues to be a major driver of development outcomes. The investment could even backfire if climate, transition and other project-related risks weaken the country’s sovereign credit rating before significant oil benefits can be reaped.

Further sovereign credit rating downgrades could create a vicious circle of capital outflows and rising debt costs of the sort experienced by many countries on the continent in the years after the COVID-19 pandemic. This scenario would reduce Uganda’s fiscal flexibility and hamper the competitiveness of the country’s growing industries, dampening long-run development prospects. Uganda would become more dependent on foreign intervention to support its development.

With the costs of investments in lower-carbon growth being driven down by accelerated global deployment rates, Uganda could profit from exploring alternative, more diversified ways of utilizing the public balance sheet, especially since the country will increasingly start to face pressure from the accelerating physical consequences of climate change. Our paper Climate-resilient development in Uganda: Adapting fiscal strategies to a changing global transition landscape compares the potential risks and returns that could arise from the oil refinery with a range of other potential investment priorities, including in climate resilience and electrification.