IEEFA Update: Atlantic Coast Pipeline Risk Is Being Borne Not by Dominion and Duke, but by Their Customers

Dominion Resources and Duke Energy say they need to build the Atlantic Coast Pipeline to meet rapidly growing demand for natural gas. But will the market really grow in the way that these utilities say that it will?

Dominion Resources and Duke Energy say they need to build the Atlantic Coast Pipeline to meet rapidly growing demand for natural gas. But will the market really grow in the way that these utilities say that it will?

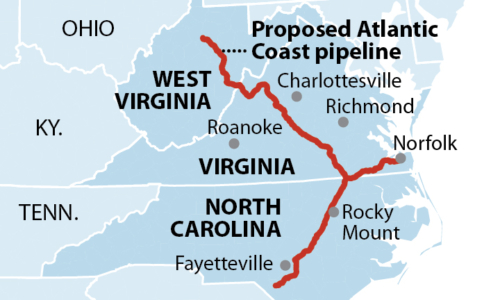

The pipeline, announced in 2014 as a joint venture between Dominion, Duke, Piedmont Natural Gas and AGL Resources, has contracted for most of the capacity—79 percent—with Dominion and Duke utility subsidiaries in Virginia and North Carolina. In their application for approval to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the developers say also that most of the gas sent through the pipeline will be used for electricity generation in those two states. The application states also that the justification for the pipeline is predicated on forecasts for rapid growth in natural gas demand.

But—as seen in recently released long-term forecasts by Duke and Dominion’s utility subsidiaries—that rapid growth may not actually materialize by as much, or as quickly, as originally thought.

FOR BOTH DOMINION AND DUKE, ACTUAL ELECTRICITY CONSUMPTION HAS BEEN ESSENTIALLY FLAT FOR THE PAST FEW YEARS, leading the utilities recently to be less optimistic about growth.

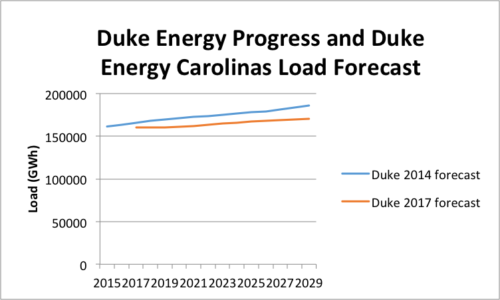

Earlier this month, Duke Energy released its integrated resource plans (15-year plans for meeting future electricity demand) for Duke Energy Progress and Duke Energy Carolinas, its two electric utility subsidiaries in North and South Carolina. As shown by the graph below, Duke has revised its long-term energy demand significantly. Duke Energy Carolinas, which was forecasting average growth of 1 percent per year in 2014, is now forecasting 0.4 percent per year growth. Duke has also reduced the new natural gas plant capacity that it plans to construct by the end of the decade.

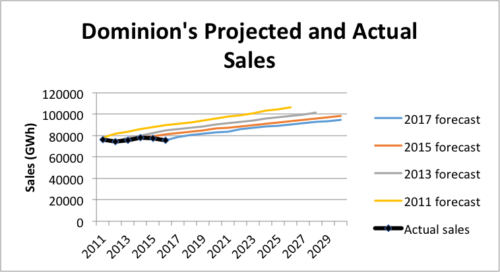

Similarly, Dominion Virginia Power’s most recent integrated resource plan shows a lower load forecast relative to the plans Dominion was putting out just a few years ago. While Dominion is still forecasting a similar trajectory of growth, it is starting today at virtually the same level of sales it reported in 2011.

In other words, in the three years since the Atlantic Coast Pipeline was first proposed, Duke and Dominion have revised their projections of future electricity demand substantially. By 2025, Duke’s forecast is lower by 10,800 gigawatt-hours (GWh) and Dominion’s by 7,700.

These are not small numbers. For context, the 1,585-megawatt combined-cycle gas plant under construction by Dominion in Greeneville, Va.—a not-insignificant project—will generate 11,000 GWh per year.

The total downward revisions in demand by Duke and Dominion—18,500 GWh —works out to about 400 million cubic feet per day of natural gas, a sizeable chunk of the pipeline’s daily 1,500-million-cubic foot capacity.

While one might think the revisions and changes in resource-development plans noted here would have a material impact on how FERC assesses the need for the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, that’s not likely—unless FERC radically alters its policy for determining “need.” Now, FERC considers a pipeline “needed” if the pipeline developer has found other companies willing to sign contracts to ship gas on the pipeline. Duke and Dominion have met this criterion—but only by contracting with their own utility subsidiaries to purchase the pipeline capacity, an investment risk ultimately borne for by the customers of those utilities.

Ironically, Duke’s and Dominion’s forecasts show exactly why it is so important to them that they build the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. With their core electric utility businesses no longer growing like were, Duke and Dominion are looking to expand into new areas—like pipelines—that offer new opportunities with little corporate risk.

Cathy Kunkel is an IEEFA energy analyst.

RELATED POSTS:

IEEFA Analysis: The Economic Frailties and Rickety Finances Behind the Dakota Access Pipeline

IEEFA Puerto Rico: The Aguirre Offshore Gas Port Is Unbankable