‘Reforms’ Across PJM’s 13-State Market Are Costly and Regressive

By Cathy Kunkel —

By Cathy Kunkel —

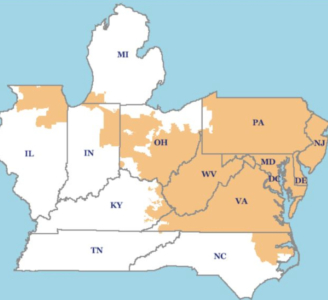

Last week, the board of PJM — the regional transmission organization that controls the wholesale electricity markets in all or parts of 13 mid-Atlantic and Midwest states — approved new changes to its capacity-market construct that would dramatically increase the price of capacity after 2018.

The reforms PJM are pushing stem from last winter’s polar vortex, in which the region was beset by electricity reliability concerns due to unexpected outages of power plants and shortages of natural gas. While the proposed changes would reward power plants that perform well during peak demand, they would penalize those that do not, and — here’s the rub — would cost ratepayers across the region an estimated $5 billion, 66 percent more than the most recent capacity price, set for 2017-18.

It’s important to keep in mind, though, that the changes aren’t a foregone conclusion: they have to be approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), which regulates wholesale electricity markets to ensure competitiveness. FERC must vote on the proposal within 60 days.

PJM operates markets in both energy and capacity. Its energy markets provide a real-time price for electricity, and its capacity market provides a price to power plants (set once a year in an auction) that keeps enough of them on the grid to meet peak demand.

PJM’s capacity market was designed ostensibly to incentivize the construction of new power plants where they are most needed, but it has done no such thing. Capacity prices across PJM’s territory have fluctuated so wildly since the market was implemented in 2007 (varying by more than a factor of 10 over the past few years) that it has failed to provide the sort of predictable cash flow required to support essential 30-year financing for new power plants.

PJM divides its territory into zones based on the amount of transmission available — if there’s not enough transmission capacity to import power into a zone at peak times, then PJM must rely on generation within that zone, which can be more expensive. Thus, capacity prices are higher in transmission-constrained zones.

If PJM’s capacity market were functioning properly, it would incentivize capacity expansion in the zones where prices are consistently high — namely in eastern PJM (New Jersey and Maryland). Instead, new capacity has been added elsewhere, and in some years, more generation has been added in western PJM (places like Ohio and western Pennsylvania) even when prices were substantially higher in eastern zones.

What PJM’s capacity market has done well is funnel money to owners of existing generating units. The only new “generation” that it has done an effective job of incentivizing is demand response, which consists of programs that reward customers who use less power during peak demand and can be developed on a much shorter time horizon and with much less capital investment than traditional power-plant construction. Companies like FirstEnergy and other power plant owners in PJM, who see demand response as competition to the generation that they own, are now seeking to limit the participation of demand response in the market.

A big beneficiary of PJM’s capacity market proposal would be the coal-fired power industry, which has lost out in recent years to natural-gas-fired plants and to gains in renewable energy and energy efficiency. Even with capacity market payments, many coal-fired power plants have struggled to remain profitable. It come as no surprise, then, that PJM — a membership organization dominated by large utilities — is moving to alter the capacity market in a way that would maintain tradition.

It’s a questionable move. PJM notes in one of its own recent reports that coal-fired power plants accounted for between a quarter and a third of the unexpected outages during the polar vortex. Meanwhile, major utilities are pushing to suppress demand response, despite the fact that PJM itself credits it with having played a large role in maintaining the stability of the electricity grid last winter.