Appalachia Needs More Than the Sound and Fury of the ‘War on Coal’ Canard

This much is evident: Coal’s share of the U.S. electricity-generation market is shrinking.

It fell to 33 percent in 2015 from 50 percent in 2005 and is showing no sign of recovery. Industry giants like Alpha Natural Resources, Arch Coal, and Peabody Energy have filed for bankruptcy and are worth only a small fraction of their former value, having dropped by more than 90 percent over the past few years.

In Appalachia, few people are celebrating this decline. Fewer still are offering a viable way forward. Industry executives and their allies only make the situation worse by spreading inflammatory “war on coal” rhetoric, blaming the modern evolution of energy markets on the Obama administration and the Environmental Protection Agency.

In Appalachia, few people are celebrating this decline. Fewer still are offering a viable way forward. Industry executives and their allies only make the situation worse by spreading inflammatory “war on coal” rhetoric, blaming the modern evolution of energy markets on the Obama administration and the Environmental Protection Agency.

The reality here is of course much more complex. Competition from low-cost natural gas along with the declining price of renewable energy has had far more effect on the coal industry than regulation, real or imagined. Industry leaders know this and have sometimes slyly acknowledged the truth, as when Robert Murray, the sound-and-fury baron of Murray Energy, embraced Donald Trump even as he urged the candidate not to overpromise on his vow to “make coal great again.”

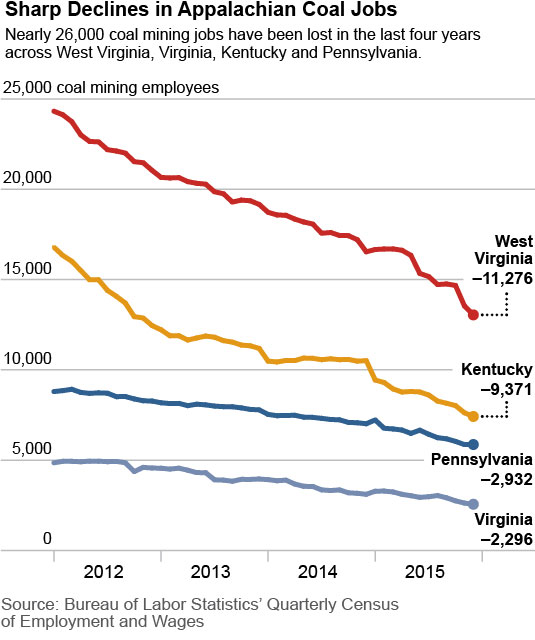

The “war on coal” narrative is built on a lie but resonates because of the economic pain that people in states like West Virginia are facing. Mining jobs in West Virginia’s southern coalfields have declined by 27 percent over the past four years, a percentage that translates into very real human terms. It means 7,000 miners have lost good-paying jobs. And in what used to be the state’s largest coal-producing county, Boone County, employment is down 58 percent.

The industry itself is compounding the pain by seeking to shed pension obligations to retired miners as part of restructuring plans that would allow companies to emerge from bankruptcy while their former employees are left to fend for themselves.

West Virginia politicians have framed the state’s financial woes in deceptively simplistic terms, too, even though the truth is more complicated. While the decline of coal has contributed to West Virginia’s current fiscal crisis, it is not the only reason for it. Coal severance-tax revenues have fallen from $320.2 million in FY 2013-14 to an estimated $198 million in FY 2015-16. But it’s also true that low natural gas prices have reduced tax revenues from that industry by more than $100 million over the same period.

State legislators have contributed to budget problems by reducing the West Virginia’s business franchise tax and corporate income tax revenues by more than $200 million a year. And unlike many other resource-dependent states like Alaska, Montana and Wyoming, West Virginia has failed to set aside any severance-tax revenues for a post-coal future.

Regardless, the “war on coal” narrative strikes a chord because it offers an explanation, however misleading, for the economic carnage that is unfolding in coal country. West Virginia’s labor force participation rate is the lowest in the U.S., less than half of West Virginians are working or are even looking for work. Although some productive small-scale economic transition initiatives have taken place over the past couple of years, none offer the scale of investment required to replace what has been lost in the coalfields.

Redeveloping the economy of Appalachia is not an impossible task—but it is a massively under-resourced one. Nascent federal initiatives funded about $80 million in grants to coal-mining communities in 2015 and 2016, not all of which were in Appalachia. This pales in comparison to the magnitude of the problem and to historic investment in similarly devastated industries. Far greater resources have been allocated, for example, to regions affected by military base closures and the decline in tobacco farming.

There are small indications that more public support is emerging. Last year, a bipartisan group of congressional representatives from the region introduced the Miners Protection Act in hopes of restoring health care benefits to 11,000 retired miners and their families who lost those benefits as a result of the Patriot Coal bankruptcy. And in February of this year, another bipartisan group of representatives from the region introduced the RECLAIM Act, which would provide $1 billion over five years for economic development on former mine sites.

These initiatives are promising, but more is required.

Stoking the “war on coal” rhetoric only prevents serious conversation about how to move forward.

Cathy Kunkel is a West Virginia-based IEEFA energy analyst.

RELATED POSTS:

Chorus of Distress Signals Suggests a Bigger Storm in U.S. Coal

Data Bite: U.S. Coal Production Is Down Almost Everywhere, and Off by Double Digits in Key States