A matter of opinion

Download Full Report

Key Findings

Major credit rating agencies have entered a new phase of more stringent credit standards regarding climate change.

Community and climate voices have become new participants that are shaping the market generally and credit agencies in particular.

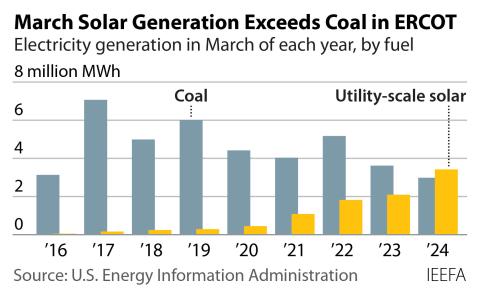

The market is likely to continue to reward low-carbon, fossil-free investments.

Climate change has become its own risk category for credit rating agencies because of regulatory, legal, economic, financial, political and social concerns.

Executive Summary

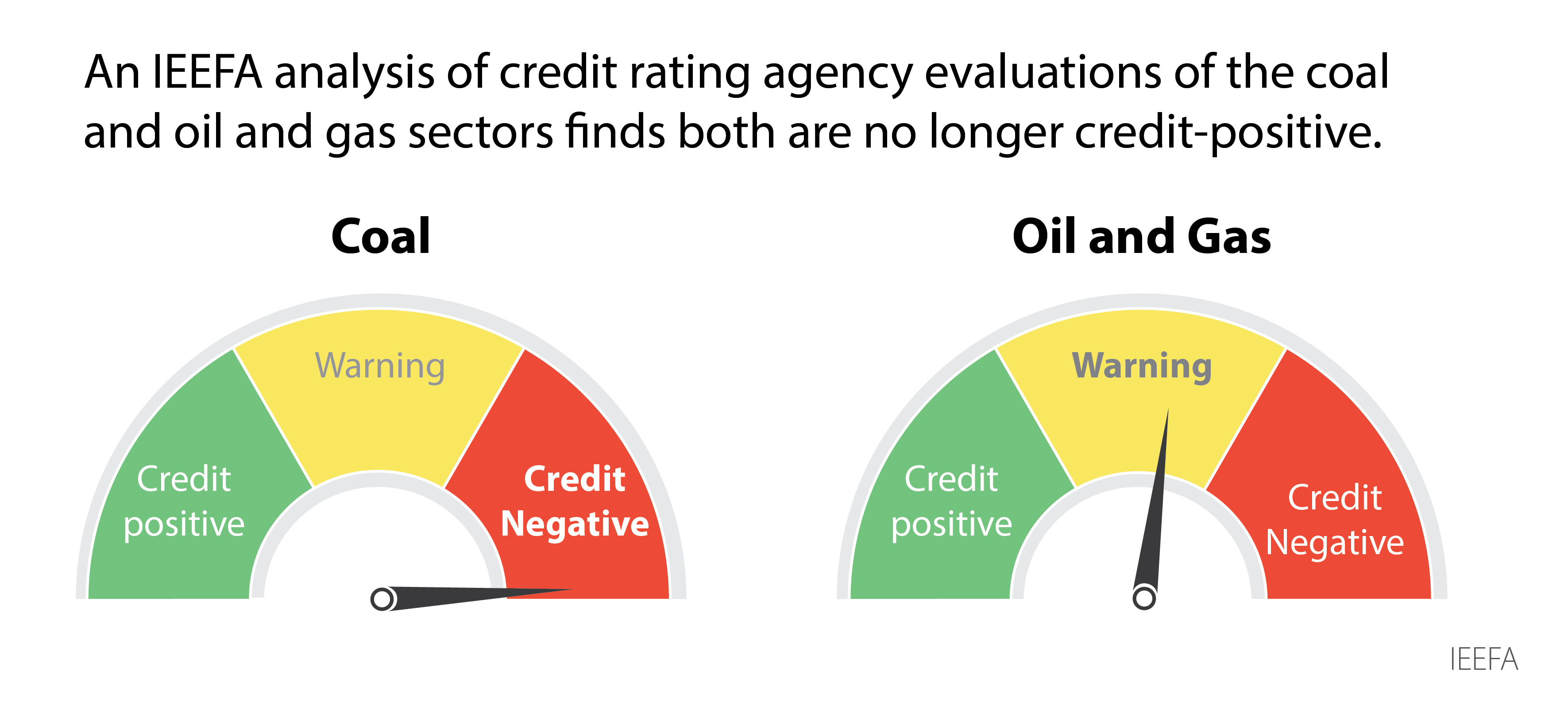

Credit rating agencies (Moody’s Investors Service, Standard and Poor’s, and Fitch Ratings) have moved almost 180 degrees in their perspective on fossil fuels during the last 20 years. A consensus has emerged. At one time, the agencies considered fossil fuels to be “credit positive.” Now, individually and in the aggregate, the three major credit rating agencies are issuing clear, specific warnings about the financial risks of fossil fuels. The opinions and approaches are varied and nuanced but clear: Coal is credit negative, and oil and gas companies confront substantial financial risks that are dampening credit ratings. Moody’s, for example, has moved its position on coal from credit positive to credit negative, and it perceives oil and gas—also once deemed credit positive—as facing a quagmire of risks.

This paper charts credit rating agency changes on climate-related risks and roots the change in the eroding fortunes of fossil fuel companies and their investors. The erosion of the coal, oil and gas sectors’ energy and financial leadership roles maps the declining significance of fossil fuels to the economic growth calculus that has served the world for decades. On the equities side, the industry has gone from a market-dominating 28% of the stock market in the 1980s to a stunning 2% of market in October 2020, more than a year before Putin invaded Ukraine. On the business side, fossil fuels face competition across the entire range of end users in electricity generation, transportation and petrochemicals. The trends are clear, and day-to-day market disruptions are unlikely to change the basic economic trajectory away from fossil fuels.

This report also identifies a new actor on the scene—“community and climate voices.” At first dismissed, these scientific, technological, environmental, community and business voices have established “facts on the ground” through persistent, well-documented, skilled, and organized activities that are increasingly finding articulation and legitimacy in institutional positions taken by energy and financial stakeholders.

Not all the community and climate voices have climate change as their priority. Some are defending communities beset by toxic pollution; others have created innovative tools to improve efficiency; and still others are seeing the move away from fossil fuels as creating business opportunities in a sustainable future. Taken together, these voices have formed an alternative, still-evolving view of a sustainable economy and are mustering the tools necessary to challenge the quasi-monopolistic power arrangements that have supported fossil fuel use for decades.

The current storyline starts in the 1960s, charting 40 years of coal, oil and gas growth fueling the global economy with rising quarterly revenues and market share, and providing a significant contribution to the world’s sovereign wealth, pension and institutional funds. The credit term for this positioning is “credit positive.” In the early 2000s, the United States embarked on a plan to expand coal use. Fueled by a flood of cheap coal and the promise of new technologies, it moved forward with a market-driven plan for 151 new coal plants. That plan and others designed to launch a new golden era of coal backfired amidst a string of market setbacks and growing public concerns.

Today, coal plants are credit negative, and oil and gas investments are a flashing yellow light, tilting toward red. The interaction of market forces and organized community and climate voices completely undermined coal’s growth plans in the United States. Though some coal plant operators in the United States and more so worldwide can navigate the increasing financial and environmental risks, coal’s position adds negatives to company risk profiles. Oil and gas—a more powerful and significant factor in any economic calculus—is also losing its competitive position, market valuation, demand, and popular support. There is still short-term money to be made in fossil fuels, but steady growth and blue-chip performance is a thing of the past.

The result: The finance sector’s oversight watchdogs, the credit rating agencies, have all moved to the arena of comprehensive credit analysis, acknowledging the impact of climate change on traditional risk areas—regulatory, legal, economic, financial, political, and social. The issue has grown to such magnitude that climate has become its own risk category.

The new, tightened standards are rooted in the financial fundamentals of credit—the ability and willingness of companies and issuers to pay back obligations. The erosion of demand for fossil fuels reduces revenues, new energy opportunities driven by cost-saving technologies are replacing fossil fuels, and the energy transition—the ability to achieve a substantial reduction of fossil fuels in the aggregate—is a story in the making. Taken as a whole, climate change is a financial risk. Financial risks require financial actions to manage or eliminate them.

The next steps for the market, credit rating agencies, and community and climate voices will be critically important. The market is likely to continue to reward low-carbon, fossil-free investments. It is also likely to begin to punish fossil fuel investments. Even periodic price spikes—although temporarily beneficial to fossil fuel producers—are now seen through a lens of volatility, inflation, societal disruption and a drag on global economic growth. Credit rating agencies will need to refine these new standards as they apply them. This will allow them to stay ahead of the curve. They play an important role in deciding whether fossil fuel companies that have made climate promises are keeping them. And community and climate voices have a far more complex task as their mission inevitably changes from marshalling the facts and bringing worldwide attention to climate change to now selecting among options that are difficult, contradictory and may have uncertain outcomes.

Credit ratings serve a very specific function in the investment decision-making process. They are not meant to be an investment recommendation just as they are not a judge of policy options. They are a broad analytical tool that assesses the ability of an enterprise to pay back debt. This paper makes clear that climate change is altering the credit landscape, including the role the credit rating agencies are playing in the process of formulating public policy.

Figure ES-1: Fossil Fuel Credit Indicator Dashboard 2023

This report focuses on institutional change. It charts the evolution of credit rating agency commentary on the risks of climate change impacts from 2000 to the present. It also describes how the evolving commentaries and risk assessments by the credit agencies reflect the continuous erosion of the creditworthiness of coal, oil, and gas companies.

This paper treats climate change as a financial risk requiring financial actions. Those actions by investors and management can be offensive (launching new investment directions) or defensive (restricting or eliminating reliance upon fossil fuels as a value proposition). Short- and long-term corporate programs by fossil fuel producers and value chain manufacturers and distributors to address climate change, once mere promises in corporate press releases, are now requiring the deployment of financial resources, as well as the assessment of profit and loss that comes with it.

This paper does not address the relationship between climate risk and environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. IEEFA has done that elsewhere.