Indonesia Wants to go Greener but PLN is Stuck with Excess Capacity from Coal-Fired Power Plants

Download Full Report

Key Findings

Japanese and Chinese investors combined have a 41% ownership interest in Indonesia’s coal independent power producer projects.

PLN is trapped in a financial straitjacket that leaves few easy options for reforms. However, PLN’s 2021 RUPTL marked a renewed commitment for Indonesia to reduce emissions.

It is undeniable that Japan and China have played a key role in Indonesia’s power infrastructure development. Japan and China have the ability to provide technology for grid upgrades, smart grid equipment, and smart appliances.

Executive Summary

Indonesia’s excessive coal power expansion over the past 15 years has been built upon the shoulders of two financial giants, Japan and China, each led dominant roles with their respective export credit agencies and public banks. The result has been alarming, with a reserve margin of 50-60% in Indonesia’s power utility company, Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN)’s main grids, accompanied by mounting debt and independent power producer (IPP) lease liabilities for the state utility, as well as a shrinking space for renewable energy to grow. As Japanese and Chinese investors reaped the benefits and returns from these over-investments, it is only logical for them to be part of the solution in supporting Indonesia’s energy transition.

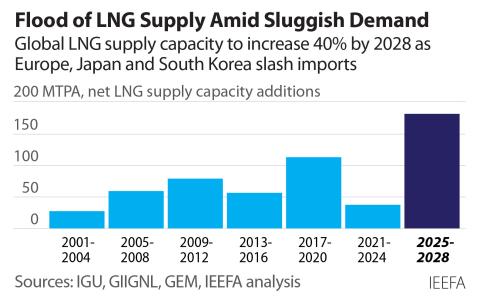

In recent weeks, at least 25 countries along with their public finance institutions have committed to ending public support for unabated fossil energy investment (by the end of 2022) at the United Nations Climate Change Conference COP26 in Glasgow. The commitment marked a significant milestone that effectively closed the door for future coal power projects, especially considering the significant role of public financiers in enabling coal power investments.

Prior to COP26, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s pledge to exit overseas coal financing coincided with similar announcements from the Prime Ministers of Japan and South Korea. In the conference, Indonesian President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) also re-announced that no further expansion of coal power would be tolerated beyond projects already in the construction pipeline. Taken together, these should reflect a new turning point to change Indonesia’s power sector direction toward the energy transition. However, PLN is already locked into unneeded baseload dirty power, as most of the coal power pipeline has been built or is under construction with strict terms and conditions in the purchase power agreements (PPA).

Since the adoption of power generation acceleration programs, the signing of new large coal PPAs has been unstoppable despite the lagging demand growth. This continued even after the leak in 2017 of a letter from the Minister of Finance to the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) and Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises (MSOE). The letter expressed concern over PLN’s financial situation, particularly its liquidity and solvency. Only in 2020 did PLN’s new management and MEMR start to publicly acknowledge the mounting financial pressure on the power company, the risks it faced on oversupply and under-demand, and its limited ability to increase tariffs.

The role of Japanese and Chinese financiers in unlocking funding for Indonesia’s coal- fired power plant (CFPP) projects is consistent with the pattern seen in other markets. The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis’ (IEEFA) data show that Japanese and Chinese investors combined have 41% of ownership interests in Indonesia’s coal IPP projects.

Sumitomo Group appears to have the largest share. China Energy Investment (Shenhua Guodian Group) and China Huadian Group came in second and third if we exclude PLN subsidiaries’ ownership in IPP projects.

Of the 31.9 gigawatts (GW) of currently installed CFPP capacity in Indonesia, 41% or 12.9GW was financed by Chinese entities, either fully or partially, while Japanese banks backed 17% or 5.5GW. As for the 13.8GW in the pipeline, at least 7.3GW have received financing from Japan or China and 2GW from South Korea. The remaining 4.5GW is still in the planning stages or under construction with limited information about reaching financial close.

Most of these investments were made possible through a project finance structure. The structure allows a developing country to acquire funding for capital intensive infrastructure projects without collateral, except for the project itself. However, this is often at the expense of a strict contract structure and a full loan or business viability guarantee from the host government.

IEEFA’s analysis on non-exhaustive datasets found that public financiers such as the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), China Development Bank (CDB), Export-Import Bank of China (CEXIM) and the Export-Import Bank of Korea (KEXIM), have all played a monumental role beyond their traditional role as investment enablers. For example, in the 2 x 1000 megawatts (MW) Batang project, JBIC had acted as the majority lender, providing IDR 29 trillion (US$2.0 billion), while a syndicate of other Japanese commercial banks including Mizuho, Sumitomo and Mitsubishi UFJ (MUFJ), provided the balance of US$ 1.4 billion.

Chinese public financiers took similar paths. Available records suggest that both CEXIM and CDB were involved as sole funders of CFPP projects, such as the 2 x 1000MW Java-7 and the 2 x 600MW Sumsel-8 mine mouth plant.

While building some coal power capacity has offered solutions in the past decades, overbuilding them has never been wise. There is every reason to believe that representatives of some of PLN’s largest IPPs and lenders would like to see PLN’s financials stabilize so they can benefit from Indonesia’s long-term growth potential. The challenge now is to find a way to bring the various parties together before there is a crisis that would limit the Jokowi Administration’s ability to map out credible options and protect the interests of vulnerable communities, ratepayers, and taxpayers.

If the big players - Japanese and Chinese IPP investors, their banks, export credit agencies, and multilaterals including the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) - seek a constructive role in resolving PLN’s problems, there are four basic steps that would support confidence in PLN and permit a transparent dialogue about durable reforms. Steps should be taken to:

1. Establish a new standard of transparent governance for any reform process including system planning, debt renegotiations, coal retirement, and new power purchase agreements granted via tender processes.

2. Conduct a thorough performance system audit for at least five of PLN’s main grid systems to provide a clear understanding of what is needed for a complete energy transition.

3. Ensure that under-performing CFPPs and proposed CFPPs in the pipeline that have not reached financial close are cancelled.

4. Accelerate a new “green” Electricity Supply Business Plan (Rencana Usaha Penyediaan Tenaga Listrik or RUPTL) process to identify cost-effective new renewables opportunities for existing and future investors.

5. Prioritize grid planning, backed by fresh investment to ensure that flexibility, resilience, and the required system services are appropriately funded to support renewables integration.

These steps would give all parties a common purpose and prevent transactional half-measures from cluttering the discussion if properly implemented.

To meet this standard, it’s crucial that discussions on renegotiation or sector restructuring should not be treated as business as usual. The Indonesian government must first acknowledge that PLN is in crisis and any panel convened to negotiate with the IPPs should also include participation of relevant ministries to ensure broad political accountability.

Decoupling short-term political goals from PLN’s planning processes might be a start. To do this, the creation of a credible and empowered independent power sector regulator could provide the unbiased authority to align policy, planning, and project implementation. A well-supported independent regulator could work with stakeholders to clarify realistic tariff assumptions and oversee PLN’s obligations to other state-owned enterprises (SOEs), influential consumer groups, and communities affected by PLN’s performance.

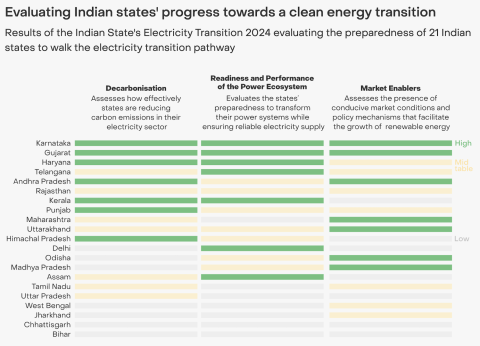

PLN’s 2021 RUPTL marked a renewed commitment for Indonesia to reduce emissions, while also highlighting the need for significant investment in renewable power capacity and grid flexibility. Of note, the “green” RUPTL includes the first serious embrace of solar technology in PLN’s future, complemented by the introduction of pumped hydro storage. Both technologies are critical to PLN’s efforts to develop the capacity and the operating skills to integrate renewables efficiently.

Even in a modest demand growth scenario, the country’s power demand is forecast to rise from 253 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2021 to 390TWh by 2030, creating meaningful market opportunities for renewable capacity. And, in turn, Japanese and Chinese investors with cost-effective renewable and storage technologies abetted by smart grid and smart appliance solutions could benefit from the same concessional financing that has been available for coal technology.