Australia's offshore industry: A half-century snapshot

Download Full Report

Key Findings

Australia’s biggest LNG customer - Japan is aiming to halve the LNG share in its electricity mix by 2030

Advanced satellite-based emission tracking systems have recently detected enormous methane leakages in remote offshore areas

Financing offshore projects are riskier as companies have lost their ability to sell down interest with partners being unwilling to commit

Offshore well depths have been rapidly increasing, exponentially inflating the capex of projects

LNG contracts have become shorter and more flexible due to the uncertain future of the LNG market

Executive Summary

On a global scale, Australia’s identified offshore gas resources are about 3 times larger than its remaining onshore resources identified so far. Australia could produce conventional gas for the next 42 years, according to Geoscience Australia, based on 2019 production rate from its currently identified conventional gas fields. 93% of these identified conventional gas fields are located in offshore Western Australia.

Gas reserves cannot be developed if we are to maintain a stable climate.

In reality however, gas reserves cannot be developed if we are to maintain a stable climate. The world has less than 3 decades to reach net zero emissions according to both the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) flagship “Net-Zero by 2050” report which urges zero new spending on oil and gas projects globally, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report which concludes global emissions must reduce by 45% by 2030 to avoid catastrophic climate collapse.

Australia took the crown from Qatar as the largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) exporter in the world in 2019, exporting 77.5 million tonnes with around 70% supplied by offshore gas.

The Federal government has actively backed the offshore oil and gas industry since the start of the LNG boom in late 2000s, with 13 exploration titles granted in 2019 alone - the highest number issued in the last decade. In the next 6 years, AUD5.1 billion will be spent by companies on offshore exploration activities in an area around 154,000km2 wide, based on work-bid data submitted to the National Offshore Petroleum Titles Administrator (NOPTA).

Oil and gas companies, on the other hand, have drilled twice as many production wells than exploration wells. These counterintuitive dynamics could be due to the fact that many companies prefer to focus on definite resources they have already explored rather than investment on risky exploration projects, despite government encouragement. They are constrained by their balance sheets as they have written off billions of dollars over the last decade on gas assets.

The top 10 biggest companies that have the highest level of involvement in Australia’s offshore sector are Australia’s oil and gas icons Woodside, Santos and BHP along with the major multi-national incumbents ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell and BP, followed by Japanese giants Mitsui, Mitsubishi and INPEX.

Of this, the top 4 operators are ExxonMobil, Woodside, Chevron and Santos. Together they operate 222 of the 373 existing offshore permits. While ExxonMobil and Woodside’s focus is on the established side of the business, controlling 51% of the production and pipeline licences together, Chevron and Santos as younger offshore players have invested more in pre-production and exploration activities, acquiring 41% of all exploration permits and retention leases as operator partners.

Of AUD5.1 billion in Australia’s offshore exploration expenditure to be spent in the next 6 years, Santos operates the most expensive projects collectively with AUD1.3 billion in expenditure. Chevron is next with AUD430 million, followed by Shell with AUD336 million. INPEX and BP complete the top-5 list, each being the operator of exploration projects costing more than AUD220 million.

Five Growing Risks in Australia’s Offshore Sector

Despite the growing number of offshore exploration permits and development projects and their prospective expenditures, IEEFA has identified 5 major risks specifically confronting Australia’s offshore sector.

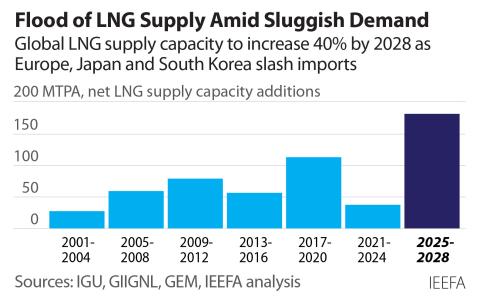

- Australia’s biggest LNG customer, Japan, is aiming to halve the LNG share in its electricity mix by 2030. There has been a massive global energy policy shift, particularly from Japan as Australia’s biggest LNG customer. Aiming for a near 50% reduction in LNG in its 2030 power generation mix, Japan will no longer be as LNG-thirsty as it used to be. This is a real threat for Australian LNG exports, especially considering the likely domino effect of Japan’s ambitious policy on other southeast Asian nations like South Korea.

- Advanced satellite-based emission tracking systems have recently detected enormous methane leakages in remote offshore areas. The emergence of advanced satellite-based emission tracking systems is providing data previously unknown or under reported, including the recent detection of enormous methane leakages in remote offshore areas. This poses a serious threat to the social license of oil and gas companies and brings into question the validity of new industry terms such as ‘carbonneutral LNG’. It also increases the risk facing bankers and investors in financing such projects, particularly as more stringent carbon emission regulations become adopted globally.

- Financing offshore projects are riskier as companies have lost their ability to sell down interest with partners being unwilling to commit. Another risk previously ignored is the changing profile of partners in joint ventures. Big oil and gas companies have lost their ability to sell down interest in billion-dollar projects due to partners being unwilling to commit. Large stakes in projects have made the cost of financing big projects higher. Financial institutions are more likely to consider higher interest rates for a project with one or two partners, compared to a project with several partners.

- Offshore well depths have been rapidly increasing, exponentially inflating the capex of projects. Based on data from 700 offshore wells, IEEFA notes that the average total depth of wells has increased by around 600 meters (20%) during the LNG boom (2009-2019). According to the scientific research, deeper drilling leads to an exponential rise in costs, even with the deployment of advanced and more efficient drilling technologies.

- LNG contracts have become shorter and more flexible due to the uncertain future of the LNG market. The current wave of country policy initiatives abandoning gas has led to customers migrating from rigid long-term (20-30 year) contracts to shorter ones (typically 10-15 years) with more flexible conditions including the ability to resell cargos in case of glut. As a result, there is now a lack of certainty that there will be enough demand for LNG cargos over the next 20- 30 years, increasing investment risk and consequently the cost of financing.