IEEFA Australia: More Wheels Fall Off the Adani Mega-Mine Train

The Adani Group has bounced back time and again with its troubled Carmichael mine proposal, but a run of freshly negative news now puts the project in real doubt.

Today the Downer Group, an Australian engineering and infrastructure firm, announced it had relinquished an A$2 billion non-binding letter of award on the project it issued in December 2014. This follows news last week that the Queensland government has formally vetoed a proposed A$1 billion loan subsidy for Carmichael and after Chinese banks said the week before they would avoid the controversial project altogether.

A point of linkage has emerged between the growing momentum of the Paris Climate Agreement and the unprecedented rate of renewable energy deflation evident globally over the past two years. The upshot: Stranded asset risks associated with greenfield thermal coal-export proposals has soared and is now off the charts.

This “brings the horizon forward” for action of climate change, as aptly noted by Geoff Summerhayes, executive director of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA).

Major financial institutions are addressing this rapidly evolving risk profile with policies to deliver on climate commitments and reduce stranded asset risk exposures by phasing out financing of new thermal coal. Among these institutions are Australian financial market leaders such as National Australia Bank and a recently growing chorus of global institutions like AXA and ING following the leads of insurance behemoths SCOR, Allianz and SwissRe.

China’s reluctance on the project—embodied by refusals to participate by China Construction Bank, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, Bank of China and most recently China Merchants Bank—dramatize the cumulative climate, stranded asset and social licence risks that make Carmichael unbankable. China is a world leader now in low-emissions technology sectors of the future, and this project is inconsistent with its “Going Global” strategy in support of the Paris Climate Agreement.

Add to all these forces the Queensland government’s veto of a North Australia Infrastructure Facility’s (NAIF) proposed A$1 billion subsidised loan to build the Adani railway line from Carmichael to the Adani Abbot Point Coal Terminal. IEEFA notes that the Queensland government’s election pledges also preclude a downscaled NAIF loan submission by Aurizon to build a railway line into the Galilee Basin, site of the proposed mine. (The government committed to vetoing “any NAIF loan that helps enable Adani’s mine, rail, power plant and/or port” and to “rule out any new direct or indirect subsidies to Adani.” All told, these statements mean Aurizon’s submission to the NAIF faces a veto like the one issued by Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk on Adani Mining.

Adani Enterprise Limited (AEL) has said it will continue on with the Carmichael proposal as an owner-operator, but we think the financial risks of commissioning and operating a 25 million-tonne-per annum (Mtpa) export mine in a foreign jurisdiction are well beyond the abilities of the current team, not the least given the scale of the greenfield proposal. While AEL has commissioned and operated a 6 Mtpa coal mine in India, its international mining experience is limited to a single Indonesian coal mine operation that has produced 5-7Mtpa since 2009, only half its original target of 12-13Mtpa.

Adani Enterprise Limited remains highly leveraged, with net debt of US$3.8 billion as of September 2017, 1.6 times AEL’s book value of shareholder funds of US$2.4bn. This leverage is compounded by the A$1.5 billion (US$1.2 billion) carrying value of the Carmichael proposal (half of AEL’s book equity), which magnifies risks after the loss of Chinese funding and Downer’s decision to withdraw.

ON A STRIKINGLY SIMILAR NOTE, THE INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY today released its “Coal 2017: Analysis and Forecasts to 2022,” an assessment that describes a “decade of stagnation” since global demand peaked in 2014.

A key driver of this downbeat report is the faster-than-expected change evident in India, the world’s second largest producer, consumer and importer of coal. In a clear acknowledgement of rapid Indian electricity sector transformation, the IEA has halved its forecast growth of Indian thermal coal demand by 2022, by 115Mt to just under 700Mtpa.

With imports providing most of the balance of Indian power sector demand that cannot be supplied by domestic coal mines, the implications for imports are even more material. The IEA has cut its thermal coal import forecast for India by 39 percent, or 65Mt, to just 102Mtpa by 2022. Imported coal simply cannot compete with renewable energy.

In light of a 50 percent decline in renewable energy tariffs to a record low R2.44/kWh (US$38 per megawatt hour (MWh)) since the start of 2016, new renewable energy projects are cheaper than many existing domestic thermal power tariffs (which generally range from Rs2-6/kWh). A November decision by the new Indian Energy minister, R.K. Singh, to lift the country’s targets to 10 gigawatts (GW) of wind and 20 GW of solar installations annually means India’s goal of 175GW of renewables by 2022 now looks decidedly conservative.

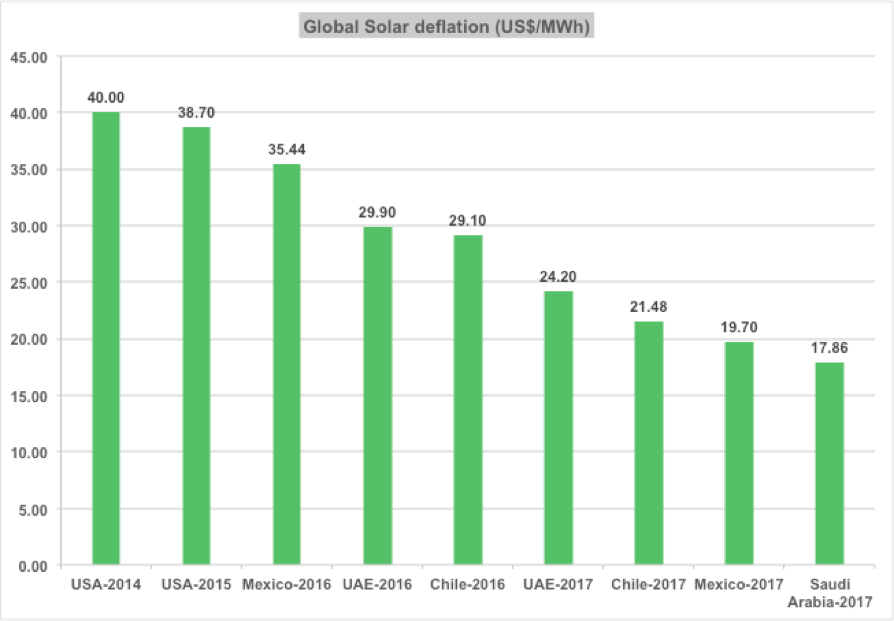

Renewable energy deflation is increasingly driving a global energy transformation, with solar tariffs down some 50 percent since the start of 2016 in Chile, Mexico, India and the UAE.

It is clear also that the same factors driving rapid deflation in solar costs are driving down the cost of both onshore and offshore wind. Greater policy certainty, lower capital costs, ongoing technology improvements, learning by doing and economies of scale are all supporting this trend. Last week saw the cost of onshore wind in Alberta, Canada, drop 55 percent to $37/MWh relative to 2016 prices. Declines of some 50 percent in onshore wind tariffs have been seen also in India and Mexico, and in the offshore wind market in Germany and the United Kingdom.

It is clear also that the same factors driving rapid deflation in solar costs are driving down the cost of both onshore and offshore wind. Greater policy certainty, lower capital costs, ongoing technology improvements, learning by doing and economies of scale are all supporting this trend. Last week saw the cost of onshore wind in Alberta, Canada, drop 55 percent to $37/MWh relative to 2016 prices. Declines of some 50 percent in onshore wind tariffs have been seen also in India and Mexico, and in the offshore wind market in Germany and the United Kingdom.

Ongoing, faster-than-expected technology-driven deflation highlights a clear and present danger to the global seaborne thermal coal sector, which is in the throes of a structural decline acknowledged just today by Roy Green, the incoming Chairman of the Port of Newcastle, the largest coal export port in the world.

“Essentially this spells a new era for Port of Newcastle,” Green said. “The world’s biggest coal port is now preparing for the end of coal.”

Adani’s Australia project is in the cross-hairs of these trends because stranded asset risks are highest for greenfield thermal coal proposals like Carmichael.

Tim Buckley is director of energy finance studies, Australasia.

RELATED ITEMS:

IEEFA Australia: Adani’s Bad Month

IEEFA Australia: Adani Is in Scramble Mode

IEEFA Australia: The Odds Against Adani’s Mega-Mine Are Growing