IEEFA Update: The Coal ‘Comeback’ of 2017

The U.S. coal industry is making a comeback.

The U.S. coal industry is making a comeback.

So goes the story being spun lately by the industry itself, even if the facts of the matter suggest something else.

The coal industry points, among other statistical threads, to the latest Short-Term Energy Outlook from the Energy Information Administration, released July 11, as a harbinger of a turnaround. The EIA forecasts U.S. coal production this year rising 8 percent over last year, and sees coal’s share of U.S. electricity generation for 2017 slightly edging out natural gas.

Some perspective is in order.

After last year, when U.S. coal production hit its lowest level since 1978, and natural gas exceeded coal’s share of electricity production for the first time in history, any gain would be seen as a headline improvement by the coal industry.

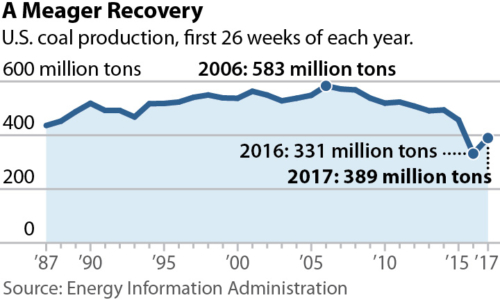

But it’s not much to hang your hat on. Coal production through the first 26 weeks of 2017 was about 389 million tons, at least 45 million tons less than in any of the past 30 years (except for 2016). For this year—the full year, January through December—the EIA forecasts total production of around 785 million tons, which would make 2017 the worst year (other than 2016) for U.S. coal producers since 1983.

A closer look at natural gas’s lower market share this year doesn’t hold much promise for a coal recovery either. In 2016, when natural gas beat out coal for electric power generation, the EIA reported that the average wholesale gas price from April 1 to July 25 was $2.27 per million BTUs. This year, that price has averaged $3.03 over the same period—a 33 percent increase—yet coal has been able only to pull back to even. Through the first half of 2017, coal’s share of electricity generation stood at 30.1 percent; natural gas, 29.4 percent. Compare that with just 10 years ago, when coal was at 48.5 percent, and natural gas was a distant 21.6 percent.

Next year? The EIA sees natural gas edging out coal again.

Two other forces aside from cheap natural gas are working against the coal-recovery tale, not just in the short term but in the longer term too.

First, and often overlooked, is that total electricity generation in the U.S. is expected to be flat or slightly lower through 2018, continuing a trend that has held most of this decade as energy-efficiency advances and warmer winter temperatures have cut demand. The EIA reported just this week that residential electricity sales have fallen 7 percent on a per-person basis since 2010. One effect of this trend: Newer, more efficient and cheaper sources of power are coming online, pushing out older plants—especially aging coal plants—in competitive power markets.

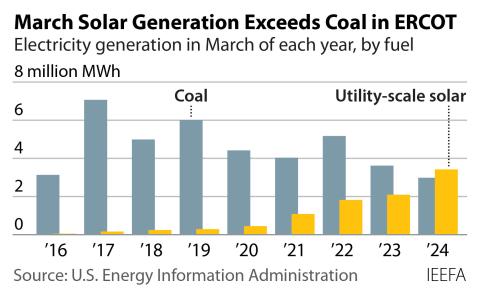

Second is the remarkably rapid growth of renewable energy, most of it from wind and solar. The EIA has non-hydro renewables picking up another 1.5 percentage points of market share by 2018, to just under 10 percent annually across the U.S., a level already passed in March and April of this year.

Across the Great Plains states, from Texas to the Dakotas, the impact from wind generation is even more profound than the national numbers convey—making it ever tougher for coal to win back market share. In April, Kansas led the country with over 50 percent of its electricity generation coming from wind. Iowa topped 53 percent in both February and March. Oklahoma, deep in the heart of oil and gas country, exceeded 40 percent in February, March and April. More significant was Texas, by far the biggest electricity-generating and coal-burning state in the country, where wind’s share accounted for more than 20 percent of electricity generation from February through March—more than twice the percentage reported in California, the state so often portrayed as the poster child for renewables.

In one vivid example the other day of how this growth in wind power is affecting coal plants, the operator of the 470-megawatt Gibbons Creek coal-fired plant in Texas announced the plant would be run only for five months a year, from June through September. The Texas Municipal Power Agency said it was economical to run the plant only during the hottest months, when power demand—and the prices paid for that power—are highest. It also happens to be the months when wind generation tends to be low.

Perhaps the best indication of how the real coal recovery story will play out may have occurred on American Electric Power’s second-quarter earnings call with investors and analysts on Thursday. AEP is one of the country’s largest electric utilities, with coal-fired plants making up nearly half of its capacity. On the earnings call, Chairman and Chief executive Nicholas Akins announced that the company would buy a 2,000-megawatt, 800-turbine wind farm to be built in the Oklahoma panhandle, along with a 350-mile high-voltage transmission line to bring the power east. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, Akins cited numerous rationales for the move, including $7 billion in customer savings over the 25-year life of the project, which could come online by mid-2020; its potential to add to AEP earnings growth; and the risk reduction it would bring by diversifying the company’s fuel mix.

What, then, of coal? Akins discussed in hopeful terms the company’s efforts in Ohio to get the legislature to enact income guarantees to bail out two of its failing coal-fired plants there. The company expects to retire another coal-fired plant in Ohio, J.M. Stuart, by the end of 2018, and either retire or sell coal-fired units in that state at the Conesville and Cardinal plants by 2022.

Seth Feaster is an IEEFA energy data analyst.

RELATED POSTS:

IEEFA Update: Across a Bedeviled Industry, Too Much Coal Is Being Mined Still for Too Few Customers